The ‘naval stores’ industry provided much-needed jobs but at a steep cost for laborers.

In the days before modern solvents, turpentine, which is derived from pine sap, was an important ingredient for everyday life. It was used in a variety of products, from paints to medicines and soaps.

Rosin, pitch and gum were also derived from the piney concoction and were critical to seal wooden ships and waterproof rigging. Since most ships were made from wood, and modern petroleum-based spirits like paint thinner and acetone were not yet available, turpentine was the go-to solvent. Because of this connection to early shipping, the business as a whole is referred to as the “naval stores” industry.

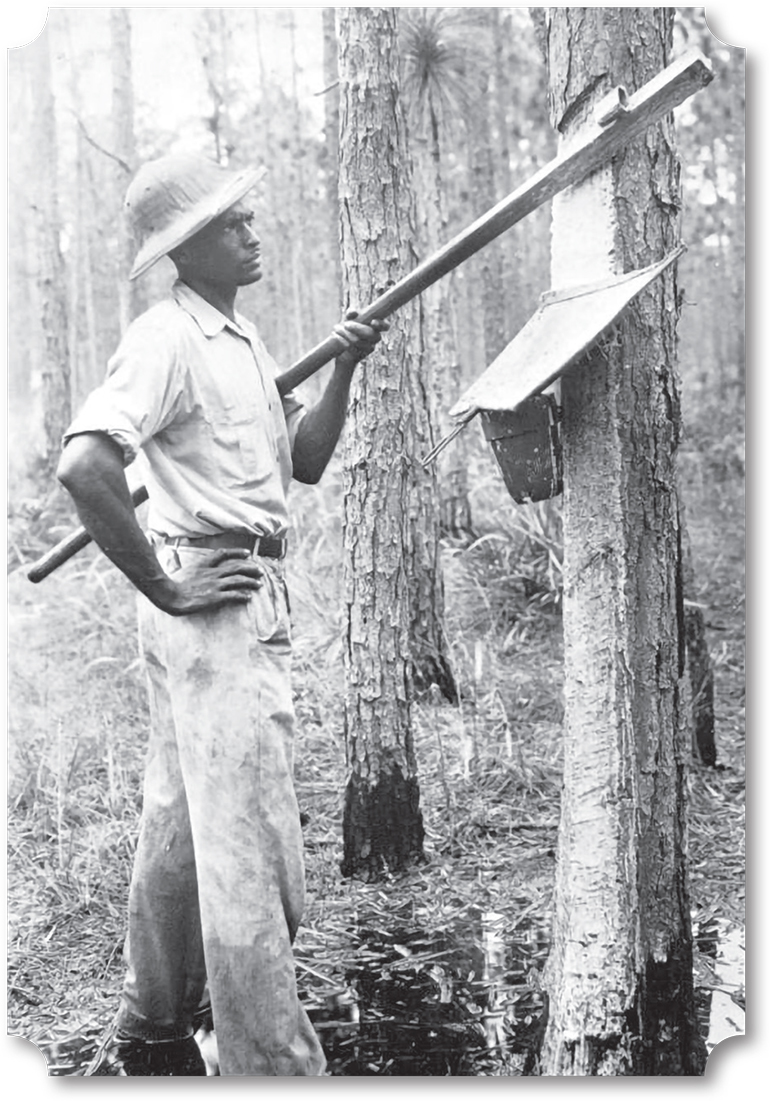

Turpentine as a commodity is labor intensive to produce. The process requires vast stands of old long leaf pine trees and legions of workers who can toil away at physically draining labor in the southern heat. The trees are cut or scored in a chevron pattern on one side to get the pine sap running. These cuts are called “cat faces” and include sheet metal drip gutters at the base that direct the sap into a cup attached to the tree. Early cups were often tin but terra cotta “Herty” cups (invented by Charles Herty in 1902) quickly became the norm once introduced.

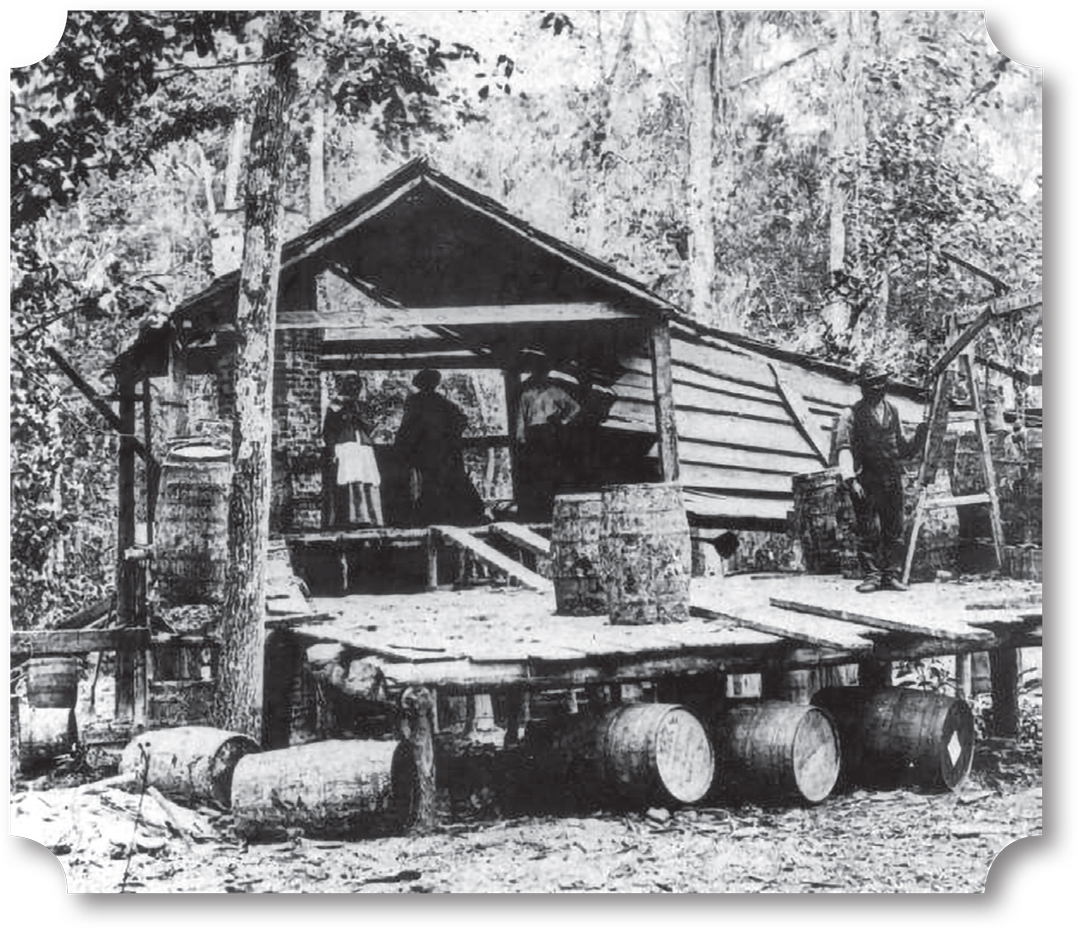

The period between the late 1800s and early 1900s saw the heyday of the naval stores industry. From about 1909 until the 1920s, Florida was one of the leading producers of these products in the nation. Larger operations were vast and included company towns known as camps. Hundreds of turpentine camps existed across north Florida and involved tens of thousands of acres. Raw pine sap would be collected and transported to a centralized distillation operation for processing. These stills cooked the sap down to produce mainly turpentine and rosin, which were then sent to market in 50-gallon wooden barrels.

Turpentine camps involved laborers and supervisors, coopers to craft barrels, cooks, wood cutters, wagons, trucks and people to run the still itself. Many camps were somewhat isolated and provided housing, schools and a company store in which workers could purchase supplies.

While the industry provided much-needed jobs, there was a steep cost for many who worked in the camps. This was hard, dirty and hot labor, done primarily by African American men in the deep south during the era of racial segregation and Jim Crow laws. Since there was money to be made, larger companies put profit before the welfare of employees and exploitation was not uncommon.

It is true that many of the workers at the camps were paid. However, supplies were only available at the camp store using company-issued scrip or coin. Prices were kept inflated to trap laborers in a cycle of debt, essentially holding them in the job. Others were even less fortunate. Prisoners were leased to naval stores operations through a convict leasing system that was akin to modern slavery. Men were arrested for trivial charges and even those deemed innocent by the courts, but who could not pay court costs, were jailed and leased for pennies to private businesses like the turpentine camps. Fees generated substantial income for state and local governments and provided what fundamentally amounted to free labor for unscrupulous bosses.

Naval stores profits began to decline due to the advent of more modern solvents, fewer wooden ships and legal scrutiny into the convict leasing system. In 1919, convict leasing was abolished by the Florida Legislature but counties were exempt, and the practice continued. In 1923, it was banned in Florida altogether after a high-profile state investigation into the death of a man named Martin Tabert in a turpentine camp uncovered corruption and the horrible treatment of prisoners.

By the late 1930s many of the camps had closed and transitioned into timber operations. Stands of pines that had once yielded the profitable sap fell to sawyers and made lumber for new construction. The naval stores industry held on in small operations for a few decades but by the early 1950s the turpentine stills of old Florida were mostly a thing of the past.

The Silver River Museum has some “Herty” cups and tools used by laborers in the turpentine camps on display. OS

Scott Mitchell is a field archaeologist, scientific illustrator and director of the Silver River Museum & Environmental Education Center at 1445 NE 58th Avenue, inside the Silver River State Park. Museum hours are 10am to 4pm Saturday and Sunday. To learn more, go to silverrivermuseum.com.