In sickness and in health, for richer or poorer, till death do us part. Many take for granted the weight of the vows made during a wedding ceremony, sometimes even the bride and groom. But for local graphic designer Nick Iannone, those words he spoke to his wife, Martha, more than two decades ago couldn’t ring more true.

When Nick Iannone started dating Martha Toothaker 26 years ago, he was smitten.

“I brought her down to The Breakers in Palm Beach to impress her with what I did for a living,” Nick says. “There were models, stylists and fancy cars.”

A smile spreads across his face as he shares what happened next.

“Martha corrected the whole photo shoot,” he laughs. “She said the doorman opened the door with improper timing and the water glasses were the wrong height for the dinner setting. At this point I was really impressed. She was just supposed to be there as a tag-along girlfriend.”

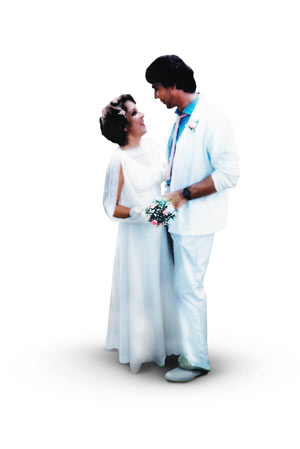

The couple married in 1986, but Nick says the wedding waltz hasn’t ended yet.

“Our relationship is like a honeymoon every day,” he says. “When people are in love and they’re apart, their bodies ache.”

On New Year’s Eve 2003, Nick, Martha and Martha’s 30-year-old daughter Mitchie, who was wheelchair-bound and suffering from complications from spina bifida, welcomed the new year with a night of dancing in the family room. The next morning, everything changed.

On January 1, 2004, Martha complained of a splitting headache down the back of her neck.

“She’s been a teacher and a nurse,” Nick says, “so when she had me look up ‘aneurysm’ I got very concerned.”

Within 30 minutes Nick wouldn’t hear another word escape his wife’s lips for two years.

“We had an answering machine and Martha was trying to figure out how to work it,” recalls Nick tearfully. “She inadvertently recorded herself saying, ‘Oh, I see.’ Those were the only words I had from her. I saved that message.”

Martha was the type of person who was always caring for others, including her daughter, both her mother and her father when they were diagnosed with terminal cancer and countless patients as an ICU/ER nurse at Munroe Regional Medical Center.

Martha was the type of person who was always caring for others, including her daughter, both her mother and her father when they were diagnosed with terminal cancer and countless patients as an ICU/ER nurse at Munroe Regional Medical Center.

Now Martha needed help herself. On January 2 she received a clip operation to stop the hemorrhage on her brain. The doctors were amazed she had made it that far. But Martha’s challenges were just beginning.

Following the surgery, there was a 50/50 chance that Martha would experience vasospasm, a condition in which blood vessels undergo vasoconstriction, ischemia and death. On the fifth day following her aneurysm, vasospasm sent Martha into a coma.

“The doctors informed me this was the worst thing that could happen,” recounts Nick. “I was told that even if she survived, she would be, at best, a vegetable. They asked if this is what she would want and [said] that I should consider her quality of life.”

Nick explained that he could only make decisions based on how he knew his wife had lived her life. He told them Martha always said that there is warmth and an absence of warmth, light and an absence of light, life and an absence of life—that cold, dark and dead were words that we use to define that which is not there.

“She’s warm, she is alive,” he told them. “This is not our decision to make.”

Nick spent the next several days at Martha’s side in the ICU, running interference between the doctors and nurses—asking questions, demanding answers and comforting Martha.

“I could feel that she was scared,” he says. “I whispered to her that she was not alone and I told her that ‘If it’s going to be too hard and you have to go, know that I love you and will be along soon enough, but if you want to come back, I’ll be here for you always.’”

Then, a miracle happened. Half an hour after Nick’s plea Martha’s left eye opened—just a slit. By morning, both eyes were open, though glassy.

“I later realized it was my birthday,” Nick recalls with a tear rolling down his cheek, “when she opened her eyes. She came back because I asked her to.”

Martha seemed to have made her decision and was ready to fight.

In an effort to defuse false hope, a nurse tried to explain to Nick that the “lights were on but nobody was home”—that you could put a stick in her eye and she wouldn’t know it. The nurse tried to emphasize this by flicking his fingers in front of her face. Martha blinked. Stunned, the nurse left to inform the doctor. Martha’s doctor had been prepared to meet with her family that night to deliver a hopeless prognosis. Instead, there was a glimmer of hope.

For three more weeks, Martha remained in the ICU as they unsuccessfully tried to get her off the ventilator. Insurance dictated she be moved to a facility specializing in such situations, so she was transferred to a hospital just south of Jacksonville.

Having depleted his vacation time, Nick would leave Ocala each day at precisely 3pm to be by Martha’s side two hours later. He did this every day for six months.

“They would kick me out at 9pm and I would get home at midnight,” he remembers. “I’d go to sleep, get up, go to work and do it all over again.

“They would kick me out at 9pm and I would get home at midnight,” he remembers. “I’d go to sleep, get up, go to work and do it all over again.

“I never knew what to expect,” Nick adds. “One day I’d arrive to find her with stable vitals, and on the next she would be convulsing.”

Four days after arriving in Jacksonville, though, Martha astounded doctors when she successfully got off her respirator.

“Even in her weak state, it was apparent Martha knew that getting the trach removed depended on her ability to clear her throat, so she worked hard on that goal,” says Nick.

As Nick watched his wife continue to fight for her life, he received another dose of devastating news. A late-night call informed Nick that Martha’s daughter, Mitchie, was in the hospital and was not expected to survive the night. He arrived in Ocala half an hour after she passed away from complications arising from her spina bifida. It was two months to the day after Martha’s aneurysm.

“I knew Mitchie was fighting an infection but was not informed of how bad it was,” says Nick. “Though I believe Martha sensed what happened, it was years before I could openly tell her that her daughter had died.”

Nick explains that Martha had always declared that if anything ever happened to her daughter, she would have no reason to live. For Nick, the idea of losing Mitchie and his beloved wife was not an option.

So Nick took action and began studying the brain and how it worked in what little free time he had. He learned about brain chemistry and restorative therapies, and practiced them with Martha every night. When he found she could blink “yes” to his questions, he fought to get doctors and nurses to recognize what she was doing. His efforts were fruitless. Three months after arriving in Jacksonville, Nick was told to face the fact that Martha would not recover from her aneurysm and that she would never get off her trach. The doctors had all but written Martha off, declaring her to be in a persistent vegetative state.

“Not acceptable,” Nick recalls of his feelings. “Martha was putting up a great fight and despite her progress, each day was a roller coaster ride.”

Stating that her vitals were sufficiently stabilized, the doctors transferred Martha to a nursing home next door to the hospital in Jacksonville.

For Martha, the fight was just beginning. Within a month she was transported to Shands at the University of Florida after Nick, from his experience with Mitchie, noticed the symptoms of progressive hydrocephalus, a condition in which cerebral spinal fluid puts pressure on the brain.

Once at Shands, a surgery was scheduled to release the pressure on Martha’s brain and Nick was thrilled when the doctors recognized Martha’s ability to communicate through blinking. Unfortunately, while saving her life, the surgery left Martha unable to communicate, even through blinking. Martha once again was totally locked in and had to start over. This time she would do it closer to home, just a 45-minute commute for Nick.

At Marion House in Ocala, Martha found a new beginning. Nick knew she was absorbing every bit of her surroundings and kept a television within view.

With more time to spend together, Nick and Martha worked on brain neuroplasticity (exercises that assist the brain with forming new connections, thereby increasing the brain’s capabilities) and muscle stimulation.

Utilizing complementary medicine techniques, Nick enlisted the help of a Reiki healer, who used therapeutic touch with Martha.

“We would see positive results three days or so after a session,” he says. “After the second session, she turned her head to a noise. So I increased sessions to twice a week.”

“Martha was beginning to come back, very slowly,” he adds. “At one point during her recovery, I was amazed when she recognized a nurse who had taken care of her while she was in a coma, acknowledging her from halfway across a crowded room.”

Two years after beginning Reiki and just before the winter holiday season, her massage therapist told Nick that Martha wanted to talk.

“For my birthday she had given me a gift of light by opening her eyes and for Christmas that year she gave me the gift of sound,” he recalls. “That was a turning point.

“Some people seek material things,” Nick continues, “but I now know a true gift. This whole experience has taught me that what is important is life. Nobody stands at the pearly gates and says, ‘I wish I’d spent more time at work.’”

Nick’s love for his wife has remained constant and enduring since her aneurysm. He usually keeps fresh flowers in her room so if she’s asleep when he stops in to visit, he gently places a flower on her sheet.

“It’s how she knows I was there,” he says softly. “Just because she’s snoozing, that doesn’t mean she can’t have someone there with her.”

Unsure of what to do with his racing mind following his wife’s aneurysm, Nick continues studying the human brain and the body’s chemistry.

“I’ve learned a lot,” he says. “Brain cells do repair themselves. We practice neuroplasticity exercises and I believe they’ve helped in giving her back her cognizance. Even the most obscure trace element may be a necessary building block.”

“‘Character,’ Martha used to tell me,” Nick adds, “‘is what you are when nobody is watching.’ That’s why I do what I do for her. I want to make her proud.”

In starts and spurts, Martha had already made great progress. Nick adds that at times she advanced very rapidly and that their life was filled with “firsts.” A first trip to the Appleton, a trip to Silver Springs, watching movies. Some of the simple things that we take for granted every day. After much discussion with Martha, Nick moved her one more time. This time to Palm Gardens, just two miles from the couple’s home. In time she blossomed, learning new skills and making friends with her CNAs and fellow residents.

Martha reached another milestone in her recovery on May 14, 2007, when she passed her swallow test, finally allowing for the removal of her feeding tube. Nick had promised Martha that if she passed the test, they would spend their May 31 anniversary at the Hilton. She enjoyed her first gourmet dinner in years and a poolside massage.

“On weekends, we either go to restaurants, or I cook for her at home,” Nick says. “Among her many accomplishments was being a chef at a Grand Cayman resort. She criticizes my cooking and has chastised me for not making the Hollandaise sauce from scratch!”

Today, more than seven years after her aneurysm, Martha is still a resident of Palm Gardens in Ocala. Before the aneurysm, Martha understood five languages; now, though still fluent in English and Spanish, she has trouble locating her words, a condition known as brocas aphasia. She can answer yes/no and multiple-choice questions, however, and she enjoys singing. She suffers from right-sided paralysis, or hemiplegia, and is wheelchair-bound.

“She has become more self-sufficient,” Nick explains with a smile. “Even without words, Martha makes her own preferences known—what she wants for dinner, what clothes to wear and what to watch on TV. For Martha, security and dependability are important. She needs structure and looks forward to time with friends playing bingo. Hopefully I can make her smile or laugh. She has a very sharp sense of humor.”

Nick has set his sights on restoring Martha’s ability to speak as well as her physical abilities, and hopes to celebrate their silver wedding anniversary this May at the Hilton.

“We’re getting older,” says Nick, “but every day is precious. As you might imagine, there are some who think my relationship with Martha is something special. The truth is that I am just being Sancho Panza to her Don Quixote. My role is to maintain the shield and lance as she fights the battles.”