From New York City to a farm in northwest Marion County, this artist works in a wide

range of mediums and many of her pieces are imbued with the spirit of animals.

Many famed artists often use the same model in numerous paintings. Claude Monet and his wife Camille Doncieux, for example, or Pablo Picasso and his lover Dora Maar.

Many famed artists often use the same model in numerous paintings. Claude Monet and his wife Camille Doncieux, for example, or Pablo Picasso and his lover Dora Maar.

Maggie Kotuk’s muse was Ietske, 1,800 pounds of gleaming black Friesian, descended from one of Europe’s oldest horse breeds.

Kotuk is a skilled artist in mediums including sculpture, painting and printmaking.

On a recent morning in the sculpture garden at her farm in Shiloh, the warmth of the sun cast a pale glow over her gentle face as she caressed the neck of her magnificent bronze statue of Ietske (Its-cah), her hand moving lovingly across the forelock and down to the signature feathered Friesian hooves.

As she offered a tour of her home and studio, Kotuk emitted energy in a quiet way that let the visitors know she meant business, while also putting them at ease. She possesses an infectious wit and has a cultured cadence indicative of her upbringing in New York City and East Hampton.

Her works have been showcased in numerous galleries and her portraits are in the collections of such esteemed New York institutions as Guild Hall Center for the Visual and Performing Arts, Parrish Art Museum and St. John’s University.

Kotuk has been a resident of Shiloh for 11 years, where she shares her farm with horses, goats, chickens, donkeys, dogs, cats and wildlife. Her most recent art show in this area was February 22nd, with painter and printmaker Michael Kemp, to benefit the acquisition and restoration of the Orange Lake Overlook, just south of McIntosh. She notes in the event program that upon arriving here in 2009, she stumbled upon the Icehouse Gallery and Studios in McIntosh, owned by artist and furniture maker George Ferreira.

“In the back building was Harmless Pleasures, a print studio, operated by Mr. Kemp. I thought I had died and gone to heaven—both buildings were filled to the brim with remarkable art,” she writes. “When I was invited into Michael’s print studio, there, right in front of me, was a ‘sign,’ engraved on the side of the 1,500-pound press: Made on East 10th Street, New York City. Eureka! I was born and raised on East 10th Street NYC! How fortuitous!”

Kemp notes in the program that though his friend and student “grew up largely in Manhattan’s East Village, she spent a rich childhood amid farms in East Hampton,” which, he says, were “a charm of young Maggie’s life.”

“To say that Maggie Kotuk has an affinity for animals would be obvious from her life,” he offers, “but it must be stressed since it is a key to her art.”

Early Development

“As a child I lived with art from the WPA era. My family collected Russian émigré art, Americans…so I grew up looking at David Burliuk, Philip Evergood, Chaim Gross, Moses and Raphael Soyer,” Kotuk muses. “I just loved them all.”

She recalls always wanting a horse as a girl, but “being born and raised in New York City, it was impossible to have a horse, but we summered in East Hampton.”

“Another inspiration is that East Hampton was filled with artists; Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning,” she offers. “The east end of Long Island was an artist’s colony. I was born in 1945 so some of the children of these artists were people I grew up with. Of course, none of their work really registered with me, it was so abstract, but horses…”

Many of Kotuk’s memories include animals, and often come with hints of joy and sorrow.

“I had a pet duck that I took to the town fair, and I was wearing all white and the duck pooped all over me,” she says, recollecting on her 10-year old self. “My duck won Most Favorite Pet at the fair. I remember coming home and my mother says ‘Oh my God, look at you.’ And I was so proud! And so, when summer was over and we had to move back to the city, I said ‘We’re going to take the duck, right.’ She said, ‘You can’t take the duck to live with us in Greenwich Village.’ I was heartbroken.”

“I had a pet duck that I took to the town fair, and I was wearing all white and the duck pooped all over me,” she says, recollecting on her 10-year old self. “My duck won Most Favorite Pet at the fair. I remember coming home and my mother says ‘Oh my God, look at you.’ And I was so proud! And so, when summer was over and we had to move back to the city, I said ‘We’re going to take the duck, right.’ She said, ‘You can’t take the duck to live with us in Greenwich Village.’ I was heartbroken.”

At age 15 she convinced her father she could work to support a horse. It was while working at a barn in East Hampton that she learned a great life lesson.

“The woman who ran the barn never paid me. And I knew I had a responsibility because my job was to support my horse. So how was I gonna do that if she didn’t pay me?” she questions. “One day I came home and my mother said, ‘Okay, Maggie, what’s wrong?’ Because mothers know these things. I burst into tears and said she is not paying me, so I don’t know how I’m going to support my horse. And she said, ‘Well you have to tell her to pay you, whether you like it or not.’ I had to, as a young girl, find my voice. It really was a moment of growing up. She started paying me.”

Between then and college, she says, her early experiences with art teachers did not go well either, so she became mostly self-taught.

In the early 1970s, while seven months pregnant with her first child, she was earning double master’s degrees at New York University (NYU) in history and education.

“I had about two credits left and I took a pottery class,” she recalls. “I made a horse out of clay and when they opened up the kiln, something had exploded—my horse—and I destroyed everybody else’s piece. I was devastated and I felt so guilty. I thought, OK, now I’ve got to try a different medium. Something that’s not going to hurt anybody.”

She next tried a figure painting class.

“Not knowing where my belly was because I’m pregnant, I’m bumping into people, students, knocking over their easels and just making a total scene,” she offers. “And then this model walked in and climbed up to take a seat and took her robe off and she, just her body, overflowed. And I said, oh my gosh, this is not esthetically pleasing. I mean I don’t want to be rude or be critical, but I realized I needed to look at things from a perspective of what pleases my eye, and that would be my way of going from then on.

“I took all my little paints and I went up to the locker room, because it was a two-story, big studio,” she remembers. “And I painted and painted for two weeks. The teacher came up to look at what I was doing and he leans over the railing and says to all the students, ‘I want you all to come up here. Now.’

“And I thought, oh God, I’m going to be ridiculed again. I can’t stand it,” she says, adding as her voice rises in intensity, “and he flipped through all of my work and he said to the others, ‘Why can’t any of you do something like this? I mean it’s original. It’s refreshing. All of you are empty.’”

“And then three weeks later I had my baby. And, of course, I had to focus on him. But that was my first encouraging episode in making art.”

Making Her Way

By the mid-1970s, along with teaching high school, adding to her family with a daughter, and embarking on farm ownership and management, Kotuk discovered an affinity for painting portraits, “almost in the genre of Alice Neel.”

“And I would tell people, I’m not here to read your ego. I am here to look at you and see what I see in you and that’s my painting. So, if you are willing for me to do that, we have a deal,” she confesses. “Some people didn’t take me up on it.”

“Some of the famous people whose portraits I’ve painted are Nicolas Nabokov, Alfonso Ossorio, Evan Frankel, Ian Hornak, Charles Gwathmey,” she observes. “There are plenty of people no one has ever heard of, including a collection of African American subjects that caught my eye as wonderful. In fact, just last week, I was contacted by a niece of one of my subjects whose portrait I did over 45 years ago.”

Kotuk imparts that she learned another valuable life lesson around 1976, when she wanted to break into the New York art scene. She knew someone who worked for a major art dealer and they met for drinks. She recalls him telling her the way to do it was to have a person “planted” at auctions to buy her works until people started to take notice. Her then husband, a lawyer, convinced her that was fraud.

Kotuk imparts that she learned another valuable life lesson around 1976, when she wanted to break into the New York art scene. She knew someone who worked for a major art dealer and they met for drinks. She recalls him telling her the way to do it was to have a person “planted” at auctions to buy her works until people started to take notice. Her then husband, a lawyer, convinced her that was fraud.

“Over time, I had various dealers in New York and their commissions kept going up, up, up,” she notes. “And I’m thinking, what am I doing this for? I don’t have to sell the art. I just love doing it, making it. I don’t have to be famous. I just found the process of doing people’s portraits very, very interesting. Trying to find something about them that maybe they didn’t even know.

“And then life changed,” she reveals. “I wanted my paintings to tell a story. I moved to scenes with people in them that had some meaning or story behind them. For example, there is a huge portrait of the woman who was my mother’s nanny, a black woman from Nassau, who was like a surrogate mother to me. I did a painting of her as a young woman leaving Nassau on a Persian carpet as a vehicle, and her three daughters. And then another portrait of her in this painting of her mother, so it’s a continuum, it keeps moving. There is Nassau on the left and the carpet brings them across to the Bed-Stuy (a nickname for an area comprised of the Village of Bedford and Stuyvesant Heights) neighborhood of Brooklyn.”

The Friesians

In the early part of the 2000s, Kotuk became “fascinated and fell in love with” the Friesian breed of horses. She traveled to Holland, where she was introduced to Ietske at a stallion show.

“She just swept me off my feet,” Kotuk recalls wistfully. “She was the quintessential Baroque warrior horse. The kind that the Dutch government wanted to continue to breed just for that purpose, to protect and maintain the massive strength and power and kindness in these horses. There’s nothing stupid or finicky about them; they are solid citizens.”

The majestic mare was in foal, but early enough that Kotuk could fly her home to her farm in East Hampton.

“What I discovered about this horse was that she had this uncanny nature where she loved to pose, so she became my muse,” Kotuk says with a grin that turns into a hearty laugh. “In other words, I would just put her someplace and say, ‘OK, stand there,’ and she would stand there, and would take different poses. I told an artist friend of mine that I wanted a humongous photograph of Ietske and he said that’s fine, we’ll roll out big reams of paper and umbrellas with lights, like for a model’s fashion shoot, in the barn. So, I finished grooming her and I thought to myself, as soon as her hoof touches that crinkled paper, she’s gonna freak out. She walked onto that paper like a pro. She was ready to go down the runway.”

“I just thought they were magical as subjects for art,” Kotuk explains about her affection for Friesians. “They are humongous, they are kind and gentle souls. And their depth of heart runs deep as a breed. I always had the utmost respect for Ietske’s temperament, character and nobility.”

“I just thought they were magical as subjects for art,” Kotuk explains about her affection for Friesians. “They are humongous, they are kind and gentle souls. And their depth of heart runs deep as a breed. I always had the utmost respect for Ietske’s temperament, character and nobility.”

Over time, Kotuk started having incredible pain in her hips and had bilateral hip surgery early in February 2007.

“At the end of February, I was out of rehab, where I learned how to walk again, and the ice had totally consumed the farm,” she expresses, pausing for a moment to love on a cat that has jumped into her lap and begun to purr. “And one day it thawed. I let all the horses out and it was time to bring them back in and the water, that had melted, iced over on a slope leading into the barn. I’m leading Ietske and she started to slip and I started to slip. All I could imagine was that I am gonna go underneath her scrambling legs, the titanium rods in my femurs are going to be broken—shattered to pieces—and no one is going to find me. So, this is going to be how I die. I said to myself, ‘If I can get out of this predicament, I have to get out of here.’”

A few months later, she notes, the multi-million-dollar farm she had created was impacted by the recession. The two events combined were too much.

“It’s never been about money for me, it’s been about having a place for my horses,” she maintains. “I could not afford, anymore, to maintain my habit. I called a friend who did a lot of horse work in Ocala and I said I want to move.”

The Progression of Her Art

Kotuk has four grandchildren. She has illustrated three children’s books and is currently working on illustrating a collection of Aesop’s fables using her original etchings.

“Give me a kid any day and I would just love to do art with them. And they love to do art,” she declares. “Between children and animals, there is a purity, a candidness, a truth. It doesn’t lie. It doesn’t have any agenda. It doesn’t have any politics. It’s pure, simple, and charming and it makes my heart sing.”

Sweeping her arm around her living room, Kotuk motions to a whimsical sculpture of a canine, then turns the face to show that the dog’s fang is stuck outside its upper lip.

Sweeping her arm around her living room, Kotuk motions to a whimsical sculpture of a canine, then turns the face to show that the dog’s fang is stuck outside its upper lip.

“It’s so goofy looking, isn’t it. I know that hooked-up fang look. Sometimes I get it myself, but nobody makes fun of me,” she says with a giggle.

Another work, in bronze, shows a young girl in a frilly outfit, clutching her pet duck, while on horseback. Sound familiar?

Continuing the tour, she notes, “These are two etchings I did with Michael Kemp and that’s an oil painting, sort of a fantasy, I’ve got my goat in there. There is folk art… carved, painted wood… the baby bull head… This is a recent painting called Young Chick Flying Up To Heaven.”

One wall is nearly dwarfed by a huge painting in bright tones.

“This painting is interactive. The eyes follow you. It’s not intentional. It’s just what happened,” Kotuk explains. “It is called The Portrait of Jimmy Nicholson. He used to hitchhike into East Hampton to go to the liquor store and we became friends. He said he was an artist and when I visited his sculpture garden, to my eyes it was a Superfund site. To him, these were his treasures. I thought, I have got to do a painting of this man because it’s wonderful… I mean this is his truth.”

In the sculpture garden, Kotuk continues an almost subconscious stream of describing her art.

“This is limestone. This is that dog digging for moles,” she explains, pointing to a pet on the edge of the garden. “This was 200 pounds when I started. You have to go through it,” she notes, pushing her hand underneath the smooth underbelly of the canine. “This is a 200-pound block of limestone,” she notes of another work. “This is my goat.”

Inside her spacious barn, one area is set aside for sculpting.

“Plaster over there, stone over here, it’s just all over the place,” she notes.

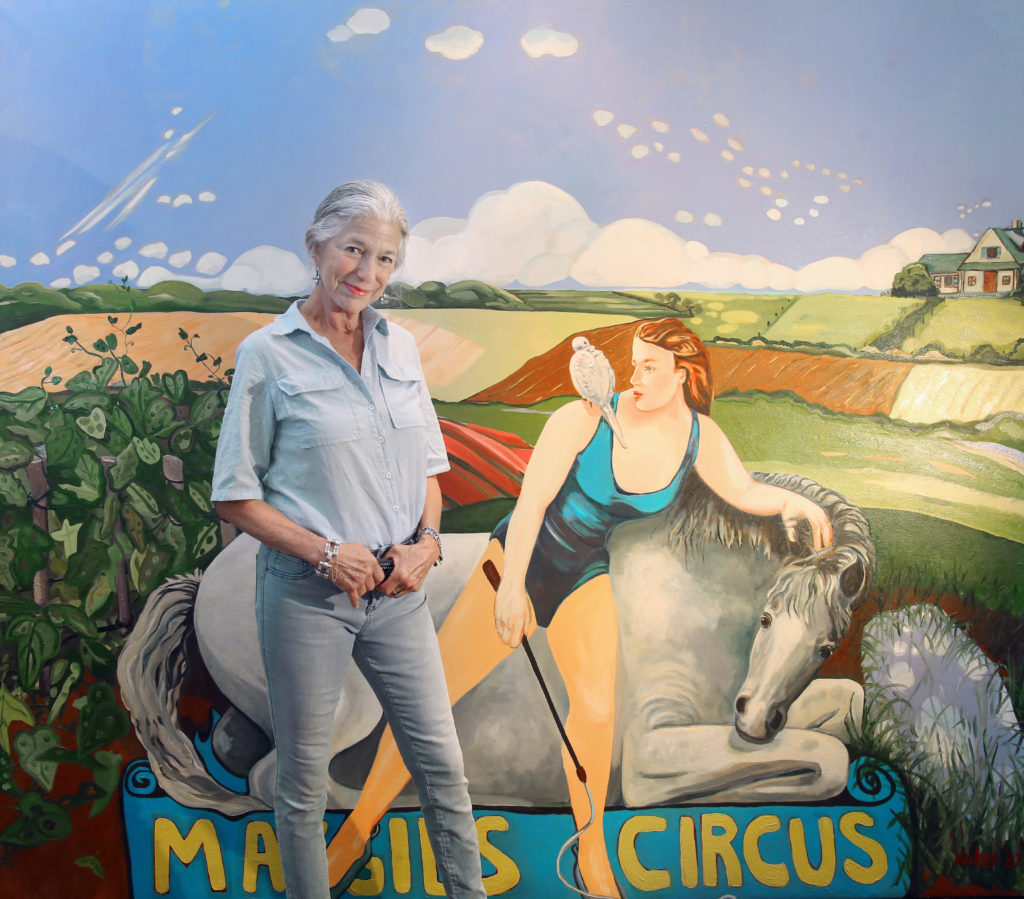

Inside her painting studio, very large paintings are nestled into racks and mounted on walls and easels. One is from her “Circus” series, in which she painted herself or family members envisioned as part of a traveling troupe. Another large work shows a naked woman in water, surrounded by animals, including a horse that is looking backward at the viewer.

“She thinks she’s alone, but she’s not,” Kotuk remarks, “because the horse is looking at us. The paintings are narratives. What I hope people will do is look at what’s on the canvas and see the story.”

Personal Perspectives

“Some artists arrive with their talents very much in place, Maggie Kotuk is one of those,” says Ferreira. “Already an accomplished painter and writer, she took an interest in sculpture after visiting my studio and gallery. I gave her a large piece of plaster from a discarded bucket of wall treatment. In this dried form it could be carved with rudimentary tools. She took this and carved two beautiful doves. From there she went on to stone and then casting bronzes.

“Just to show her work ethic,” he adds, “a fellow sculptor and I, Charlie Williams, gifted her a 200-pound block of limestone cut from a larger block. All of us had a piece of equal size with a smaller section left over. We are still carving on our sections while Maggie completed her first piece and we gave her the smaller block, 100-pounds, and she finished another work. We are inspired by her commitment to create, and thankful for her friendship.”

“Just to show her work ethic,” he adds, “a fellow sculptor and I, Charlie Williams, gifted her a 200-pound block of limestone cut from a larger block. All of us had a piece of equal size with a smaller section left over. We are still carving on our sections while Maggie completed her first piece and we gave her the smaller block, 100-pounds, and she finished another work. We are inspired by her commitment to create, and thankful for her friendship.”

“Maggie produces works which have a museum quality finish even as they exude human creativity and reverence for the sentient world,” Kemp offers.

Katherine Weissman, a writer in New York City, knew Kotuk in high school.

“We lived a few blocks apart in Greenwich Village, and I think fancied ourselves quite bohemian,” she offers. “Many of the kids in our class had gone to school together since the age of 4, but Maggie and I weren’t among them, and maybe it was that ‘outsider’ status that drew us together. Then as now, she was passionate about horses and had one of her own.”

Weissman says they lost touch when they started college, but reconnected at their 50th high school reunion.

“It was as if no time had passed, as if the adolescent girl inside each of us had just been waiting for a chance to reemerge—and giggle. We don’t see each other that often, but we email and write and support each other as best we can. I am in awe of her paintings and woodcuts and especially her sculpture. The idea of her attacking a block of stone is both amazing and utterly consistent with her strength of mind and body. Hers is a mighty talent.”

Together in Spirit

Seated inside her home, surrounded by her art and several pets, Kotuk shares that in late July Ietske developed chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

“I was at her beck and call, and it was my pleasure,” she shares softly. “I did as best I could to keep her comfortable. And then it was time to let her go.”

“I have learned some things about life and death through these animals, and that’s why I love to paint them,” she continues. “And that’s why I love to immortalize them in soapstone, or alabaster or limestone, because what they signify is so profound. She was a gift to me and I don’t want to lose sight of that in all the sadness I feel. And I feel that about all the animals and people I have lost, that in some way they stay with me.”

“All of my animals are my subject matter, so they have a purpose,” she avers. “They are a feast for my eyes, for my heart. They mean everything to me. I hope to find, through my art, the secrets that all these animals hold, of…of life. Does that make sense?”

To learn more, visit www.maggiekotukart.com