Reading, writing, and arithmetic aren’t what they used to be. Sure, high school students still take algebra and biology, but they’re also taking a variety of more specialized courses. Electives like forensic science, genetics, veterinary medicine, and sculpture are popping up in schools throughout the United States. Florida is no exception. Area schools are offering a greater selection of elective classes—both in the arts and in the core academic arenas—helping young students prepare for college and their future careers. We sat down with several local teachers who instruct some of these unusual classes. Here’s what they had to say.

Jennifer Lewis, East Ridge High

‘I’m A Total

Romantic’

Jennifer Lewis, Classical

Literature Honors

Jennifer Lewis laughs when she says she’s been teaching since she was 4 years old. (Picture her with stuffed animals and neighborhood children lined up.) As someone who’s always had a love for books, teaching English seemed the logical step. While teaching a chapter on mythology, she fell in love.

A teacher for 14 years, Jennifer’s now in her second year of teaching at East Ridge High School. When she learned mythology wasn’t a regular offering on the course schedule, she took action.

“It broke my heart to leave my baby [her mythology class] back in North Carolina,” she says. “I got the course approved here and now we’re back in business.”

Jennifer’s Classical Literature Honors course is one that encourages students to think outside the realm of possibility.

“I had to really delve into mythology, and I became voracious about it,” she says. “There’s a suspension of belief that’s required where you just have to go with the story.”

Jennifer says the best part about teaching mythology is her students’ reaction.

“There’s so much modern allusion to mythology,” she explains. “In advertising and movies, the mythological word is often referred to. Now, when someone says, ‘It was a Herculean task,’ my students know what that means. They think it’s cool.”

Jennifer is thrilled that students register voluntarily for the elective English course and already have an interest in the topics she teaches.

“Classical literature means coming from the classical world,” Jennifer says. “We focus on Greece and Rome—from the earliest known times through the Reformation—because they’re the foundation for the Western world. As an English class, we still learn about grammar, vocabulary, and writing.”

Jennifer’s personal favorite is the story of Pyramus and Thisbe, the story on which Romeo and Juliet was based.

“I’m a total romantic and Shakespeare fan,” she says. “We also study Aesop’s Fables, The Iliad, and The Odyssey, plus Gilgamesh, Homer, and Socrates.”

And that’s just the beginning.

Jennifer says studying classical literature will give her students an extensive vocabulary that should help with FCAT scores.

“Latin morphemes are key in language,” she says. “Research indicates knowledge of 10 prefixes, 30 roots, and 10 suffixes unlocks the meaning of 100,000 words. That’s pretty impressive.”

Scott McKenzie, East Ridge High School

‘The O.J.

Case Gets

Them Going’

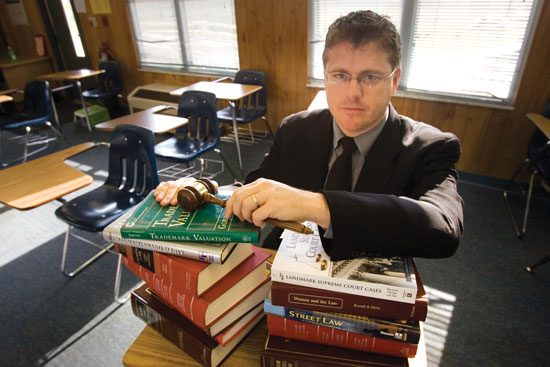

Scott McKenzie, Law Academy

The hours are as long as ever for lawyer Scott McKenzie, but the work is a lot less litigious than it was just three years ago. He’s still early to the office every morning and late to leave, but defending Microsoft in lawsuits and poring over case details has been replaced these days with staging mock trials, explaining Supreme Court decisions, and fielding questions from students instead of counsel.

“I practiced for five years in Seattle and got burned out,” says McKenzie, who teaches at East Ridge High School. “I wanted to try something different, but I didn’t want to completely abandon the field.”

In East Ridge High’s budding Law Academy program back in his home state, the one-time education major found an opportunity to couple his legal background with his teaching ambitions. The program, a sub-academy of the high school’s Human Services Academy, is comprised of a series of legal classes—Law Studies & Political Science, Court Procedures & Legal Systems, Civics, and Constitutional Law—which Scott describes as “a mini-law school.” For East Ridge high school students with aspirations of a legal career, the classes can be illuminating.

“If they stick with it, they’ll know if this is something they want to do once they go to college,” Scott says.

The courses, which serve as electives, are rigorous. Students regularly write IRAC (Issue, Rule, Analysis, Conclusion) briefs on court cases—just as they would in law school—in both Court Procedures and Constitutional Law. In the latter class, Scott guides students through detailed analysis of each amendment of the U.S. Constitution and close examination of Supreme Court decisions.

Sometimes, the cases are controversial, and Scott finds most students are not afraid to voice their own dissenting opinion.

“They may not agree with every decision,” he says, “but at least by the end, they understand it.”

Mock trials are a popular part of the Law Academy curriculum, particularly one that recounts a famous football player’s trial.

“The O.J. case,” Scott says with a nod and a smile. “That gets them going. It’s a good case to look at because we get to talk about the different burdens of proof in civil versus criminal cases.”

To cover the civil end of the legal spectrum, Scott has students try a hypothetical case in which Morgan Spurlock of the documentary film Supersize Me has decided to sue McDonalds for making him overweight and unhealthy. Without fail, students become enthralled with the lawsuit.

“O.J. and Supersize Me, those are the two cases that I think they enjoy the most,” Scott says.

The back-and-forth conversation that goes on in the Law Academy courses creates a unique learning environment students don’t find anywhere else on campus. The dialogue expands their perspective on law and its everyday application, but also refreshes their teacher’s appreciation for the subject matter.

“The kids get so involved here. It’s exciting,” Scott says. “They re-energize me.”

Karyl Elton, East Ridge High School

‘A Heart

For Music’

Karyl Elton, Chorus/Madrigal

When you think of music that teenagers listen to, artists like Rihanna, Coldplay, and Metro Station may come to mind. Well, for one talented group of vocalists at Leesburg High School, Renaissance music is often the melody of choice.

In order to qualify for Karyl Elton’s Madrigal music class at East Ridge High School, students must undergo an extensive audition that includes singing an assigned part in a quartet and learning and executing choreography. When the process is complete, 20 or so gifted students have the privilege of donning their handmade Renaissance costumes and performing for the people of Central Florida.

A music teacher for 31 years, Karyl is a Leesburg native who graduated from the very school where she teaches. She jokes that she’s been “walking the halls of Leesburg High forever.”

“I was actually in Madrigal when I was a student here,” she says with a smile. “It’s wonderful to be back in my hometown.”

Karyl credits her own choral involvement with introducing her to musical styles she wouldn’t have known otherwise. She hopes her classes do they same for her students.

“If you give them great music to sing, they’ll enjoy it,” she says. “That’s my goal each summer—to pick good choral literature for my class. I try to choose from all time periods including Baroque and Classical. The kids also sing in a variety of languages including French, German, Latin, and Italian.

“This course really helps the students get an appreciation of other cultures,” Karyl adds. “They learn to appreciate poetry and music and get an intellectual understanding of what a poet is trying to say and how the message applies to everyday life.”

Karyl is proud to say that in an “iPod world,” her students seem to have a great variety of musical selections downloaded. Her class possibly helps play a role in her students’ musical interests. Posters from such Broadway plays as Annie Get Your Gun, Oklahoma, Li’l Abner, and The Music Man adorn the walls of Karyl’s classroom—reminding her students that the world is full of good music.

“The kids perform a variety of styles throughout the year,” Karyl says. “Madrigal or Renaissance music is generally four- to six-part, a cappella music. It’s polyphonic, which means each part comes in separately.”

Sound complicated? Karyl admits that it can be.

“It’s very intellectual and challenging music to perform,” she says. “I don’t conduct the kids. I prepare them and give them directions and suggestions, but then I back up and allow them to present their creation to the public.”

For Karyl, one of her highlights each year is witnessing the vocal maturity in her students.

“From the beginning to the end of the year, the difference is positive,” she says. “These kids really have a heart for music.”

Suzanne Leclaire, Tavares High School

‘A Tidy

Classroom?

Where’s The

Creativity In

That?’

Suzanne Leclaire, AP Art

Tavares High School’s art room is a kind of controlled chaos. At any given time during a school day, students may be working with clay, building a papier-mâché piece, or creating a Pollock-esque painting. Sometimes, all three at once.

“A tidy classroom? Where’s the creativity in that?” Tavares High art teacher Suzanne Leclaire asks with a laugh. “If someone were to walk in my room in the middle of a class, they would probably think it was chaos. But it’s organized chaos.”

What is important to Suzanne is keeping all of her students on task. Seventeen years into her tenure at Tavares High and she’s done just that, especially in her challenging Advanced Placement Art class. The first time AP Art was offered at the school was Suzanne’s second year at Tavares High. Absent for only a few terms when resources were thin, the class today is a popular, albeit rigorous, choice for serious art students. Last year, nine students completed the course and sent portfolios to the College Board for evaluation.

The board requires three portfolios from each AP art student: one in drawing, a second in 2-D design, and a third in 3-D design. Each portfolio is broken down into three sections: quality (five actual pieces of work), breadth (12 slides of work), and concentration (also 12 slides of work).

“With the concentration section, the student comes up with an idea and then develops it through their artwork,” explains Suzanne. “It might have something to do with family or it could be related to art history or even a new building that’s being constructed in town that they want to document through their art.”

Artist-educators grade the individual portfolios and the student is given a final AP score between 1 (“no recommendation”) and 5 (“extremely well qualified”). Ultimately, colleges and universities decide whether or not an AP score—usually only a three or higher—will be accepted as credit.

“Art schools are a little fussier, so the AP class might take the place of an elective but not a foundation class,” Suzanne adds.

Striking a creative mood in the classroom is essential to Suzanne who is known to read literature aloud during class or play music while students work. She played jazz and dimmed the lights when her AP class was studying expressionism last year.

“If the project is something that doesn’t require a lot of input, I’ll read stories to them while they’re working, and I find that keeps them focused a little bit better,” she says. “And hopefully, I’ll instill a love of literature all the while.”

Suzanne has had numerous students continue in an art-related field—from designing special effects in movies to becoming art teachers themselves. But she says her ultimate goal is a simple one: to help students develop an appreciation for the arts.

“I want to enrich their lives, maybe weave a few gold threads into the fabrics of their lives.”

Rhonda Brown, East Ridge High School

‘Kids Love The

Gory Stuff’

Rhonda Brown—Forensics

Crime scene tape across the entryway warns that the unthinkable may have happened. Bullet holes litter the glass door. Just as your heart begins to pound, the bell rings. Fortunately, this is not an active crime scene. It’s a popular science class at East Ridge High School in Clermont.

As an inner-city middle school teacher up north, Rhonda Brown worked hard to come up with interesting ways to make kids care about science. This was long before shows like CSI: Crime Scene Investigation, Bones, and Cold Case Files were popular.

“One day I engrossed the kids with a story about law enforcement and science,” Brown says. “They were riveted. Ever since then, I’ve included a section on forensics in each of my science classes.”

After moving to Florida, though, Rhonda took her passion one step further. Receiving approval from the state, Rhonda wrote Florida’s first forensics course curriculum. Today, forensics is offered in three schools in Lake County alone.

The class is so popular, a Forensics II course has been added, delving deeper into the world of crime and science. It’s easy to understand why the students are so interested.

“Using a variety of scientific principles, the students learn to analyze a crime scene and mysterious white powder,” she says. “Plus they learn about toxicology, fingerprinting, DNA, ballistics, criminal profiling, arson/explosions, entomology, and more.”

Rhonda adds that while the topics are interesting, they are by no means simple.

“Some kids are surprised by how difficult and involved the class is,” she says. “We cover many sciences including physics when analyzing blood splatter, biology when studying DNA, and chemistry comes into play when learning about the pH of soil or the spectrum of light. They have to know solid scientific concepts and how they relate to the legal world. The forensic application is just the hook that keeps them interested.”

And you can bet with a topic like forensics, the tools of the trade are just as interesting as the stories. Instead of beakers, dissecting trays, and test tubes, students work with artificial—and real—bones and skulls, fake blood, maggots, and Mountain Dew (a stand-in for urine).

“The kids love the gory stuff,” Rhonda says, laughing. “They tend to be very interested when we’re talking about traumatic things like death and injury analysis.”

Rhonda also adds that another level of authenticity to her class comes from the guest speakers she’s able to bring in.

“The arson and bomb squad brought their vehicles and robots, which was exciting for the kids,” she says. “When the medical examiner came, he was very impressed with the kids’ level of education on the topic. He said they seemed to know more than some of the new officers coming into the office. That comment really made the students feel special.”

A true teacher at heart, Rhonda’s goodwill stretches far beyond the classroom. Two years ago she was awarded the Disney Teacherrific Award for her work with Tavares High teacher Jackie Davenport in developing the PACT program.

“It stands for Preventing Adolescent Crime Together,” Rhonda says. “High school kids get together with middle schools and mentor them about staying out of trouble with the law.”

Seeing her students grow and succeed makes Rhonda the happiest.

“I feel very fortunate they gave me the opportunity to teach this course,” she says. “Never in my wildest dreams did I think it would explode the way it did, though. It’s wonderful.”