Historic downtown Ocala is brimming with history and full of new promise.

“When I moved here in 1978, downtown was a ghost town,” recalls Brian Stoothoff, retired assistant chief of Ocala Fire Rescue, researcher and organizer behind the Ocala Fire Museum and a board member with Historic Ocala Preservation Society (HOPS). “Today it looks better than I’ve ever seen it.”

It’s an interesting starting point for our discussion about our city, the historical trajectory of America’s downtowns over time and the current trend in downtown revitalization that has been growing in momentum over the past two decades. Ocala is a prime example of a downtown that has weathered significant periods of decline but is growing in encouraging ways.

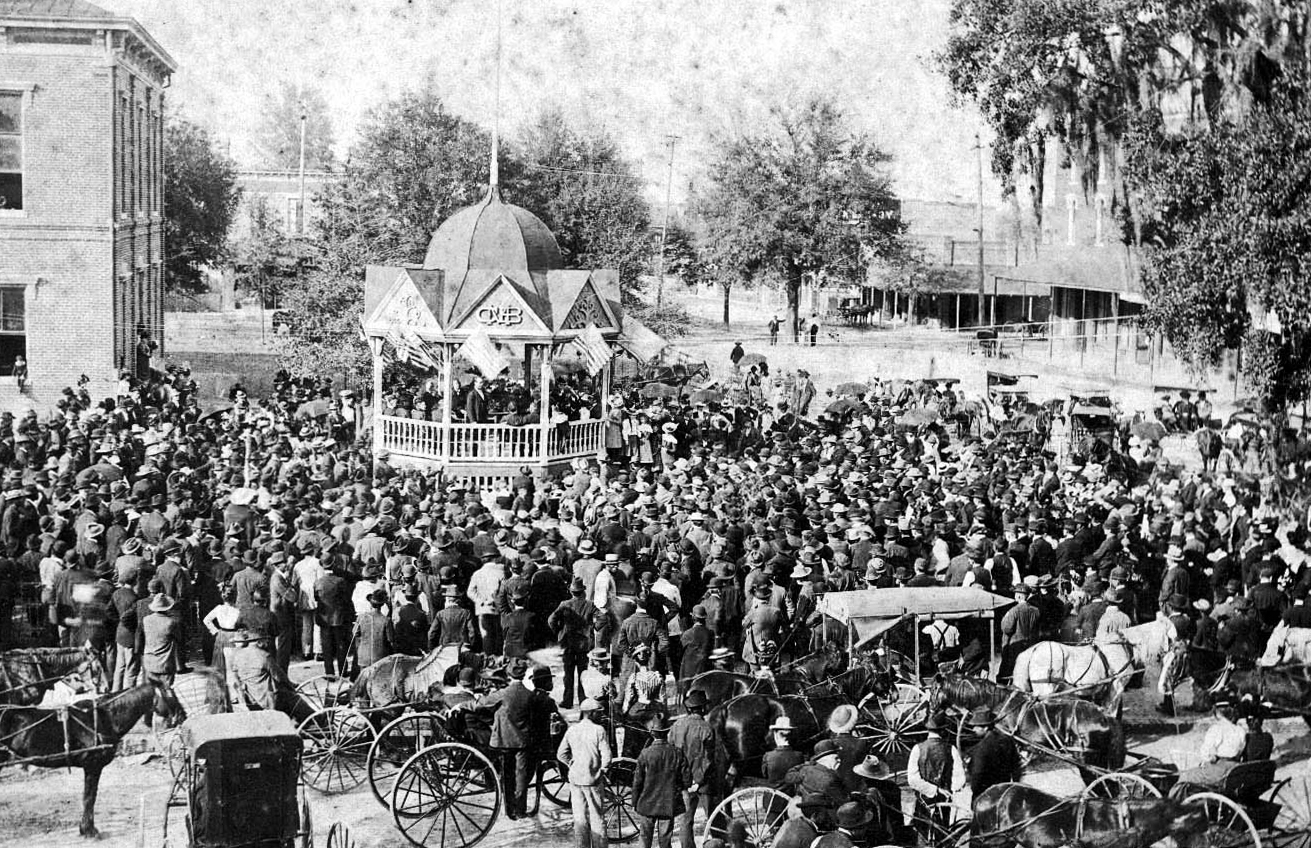

The American downtown has long been a symbol of idealized unity, a public place we can all share in, a place of interaction and connection, a place for community gatherings and where we can assemble to be seen and heard during the times of division and disconnection in our community and the world. At its very core, it is a place that represents our collective history and civic pride.

In her book Downtown America: A History of the Place and the People Who Made It, Alison Isenberg says, “Downtown America was once the vibrant urban center romanticized in a Petula Clark song. But in the second half of the 20th century, “downtown” became a shadow of its former self, succumbing to economic competition and commercial decline. And the death of Main Streets across the country came to be seen as sadly inexorable, like the passing of an aged loved one.”

Which brings up an interesting question. Why doesn’t Ocala have a Main Street? The answer is that during the 1960s, old Main Street was renamed 1st Avenue during the conversion to the new quadrant system of giving streets numbers in place of street names.

While we no longer have a Main Street, we do have Ocala Main Street (OMS), a 501(c)(3) nonprofit supporting downtown and midtown Ocala businesses. The program is an accredited member of the Florida Main Street and Main Street America programs, which exist all over the country and follow the same four-point approach: organization, promotion, design and economic vitality of the main street’s district.

“Our geographic footprint spans from the S-Curve to the Reilly, and 301 to Watula Avenue, so OMS focuses our initiatives and programs within that area. We provide contract services with the city of Ocala since our district is the same as the city’s community redevelopment area,” explains Executive Director Jessica Fieldhouse. “Our focus over the next few years is to create connectivity within the district by activating the OTrak and underutilized public spaces, connecting key destinations of the district, as well as create a place-based district by creating a livable downtown that celebrates art, historic preservation and Ocala’s unique assets.”

OMS is working to rebrand the three distinct zones of the OMS district, “which are downtown, midtown and Tuscawilla Park,” Fieldhouse shares. “When someone is in one of those zones, we want them to know exactly where they are from the branded pole banners to the colors on the crosswalks, benches and even the trashcans. We believe that creating gateways into the different areas will not only add to the sense of place, but also create visual distinction from downtown to midtown to Tuscawilla. We hope to have the downtown zone rolled out by July, as Ocala Main Street is hosting this year’s Preservation on Main Street state conference, an annual event co-organized by the Florida Main Street and Florida Trust for Historic Preservation that brings together preservationists to illustrate that historic preservation and economic revitalization are interconnected.”

According to the 2021 documentary, Downtown: A New American Dream, a significant number of people are moving back into America’s downtowns looking for a new way of living. The film’s director, Andrew R. Cline, Ph.D., describes it as “New Urbanism and the re-imagining of urban centers across the US.”

This cultural trend has certainly also been on the rise in Ocala, where, over several decades, forces combined to make the downtown district less desirable and less populated, as Stoothoff first observed. This was not unique to Ocala. The Great Depression hit America’s metropolitan areas with a brute force. Most historians link the downfall of America’s downtowns to subsidized government economic recovery programs introduced in the late 1940s to encourage home ownership through suburban developments of mass-produced houses, on affordable land, acquired through low-cost loans that lured middle- and working-class families away from cities. Also at play was the rise of the automobile industry, which relentlessly promoted the use of private automobiles and the massive highway projects that tore through downtown areas, so all those newly minted suburbanites had a place to drive those automobiles. As this huge exodus was occurring, residents and businesses who remained in urban areas saw their communities crumble. Many downtowns continued to decline for decades and never recovered.

In his film, Cline highlights the trend of many Americans, and specifically Millennials and Boomers, who are trading their cars and lawns for “a vibrant urban place where they can walk to the important destinations of life.” This growing trend of those seeking a downsized and sustainable way of life, which downtowns can provide, are moving back to revitalized small and mid-sized cities, which in turn is feeding their revitalization.

This kind of growth does not come without its challenges as cities struggle to scale and accommodate these growing urban populations and visitors descending on these districts to join in the vibrant scene downtown. And with a series of new downtown condo projects being discussed, the notion of Ocala becoming an urban oasis could soon be a reality. If we can only find a place for all those people to park—an issue that has been a stumbling point for the district for decades.

Stoothoff moved to Ocala from New York to attend college and enjoy the Florida weather. Over his time living in the community, he has become a devoted steward of its history. Perhaps it was his connection to fire that made him a match for Ocala, considering its history is inextricably linked to a devastating blaze—but we’re not quite at that part of our story yet.

Stories of local happenings, past and present, are a bit of an obsession for many Ocalans. There is an abundance of people from various birthplaces, vocations and backgrounds who now relish in uncovering and celebrating every little detail they can about Ocala’s rich history. From publishers and business owners to artists and musicians, each carry a bit of that history and have become passionate storytellers and amateur historians. I include myself among those ranks. After several years of ferreting out details about historic whiskey men and trailblazing women, I am still excited to chase down obscure details and ghosts of the past.

But the most prominent steward of Marion County’s history is the late, great journalist and historian David Cook. His research actually began when he was a student at Ocala High School. Cook not only knew all the stories, but he shared them with great aplomb. He is as important to the history of our community as any landmark building or artifact and his dispatches under the title “The Way It Was” for the Ocala Star-Banner (over 2,000 articles during a 35-year period) and the books that represent his dedication to the subject will ensure the stories remain alive for future generations.

Big Picture

The first residents of what is now Marion County were the Native American Timucua (tee-MOO-qua) tribe. Spanish conquistador Hernando de Soto observed that their territory stretched throughout Central Florida and one of their largest villages and chiefdoms was situated between the East and West coasts, in the vicinity of present-day Ocala. The original name was a source of some confusion and various versions, including Ocali, Ocale, Ocaly and even Cale were reported by visitors. This may have been an early signal of a mild identity crisis, as even after settling on Ocala as the name for the modern-day city, it has had as many as five monikers over the years. Whatever the original spelling, the name is believed to mean “Big Hammock” in the Timucua language. It is still used today and there is both a local brewery and race series that bear the name.

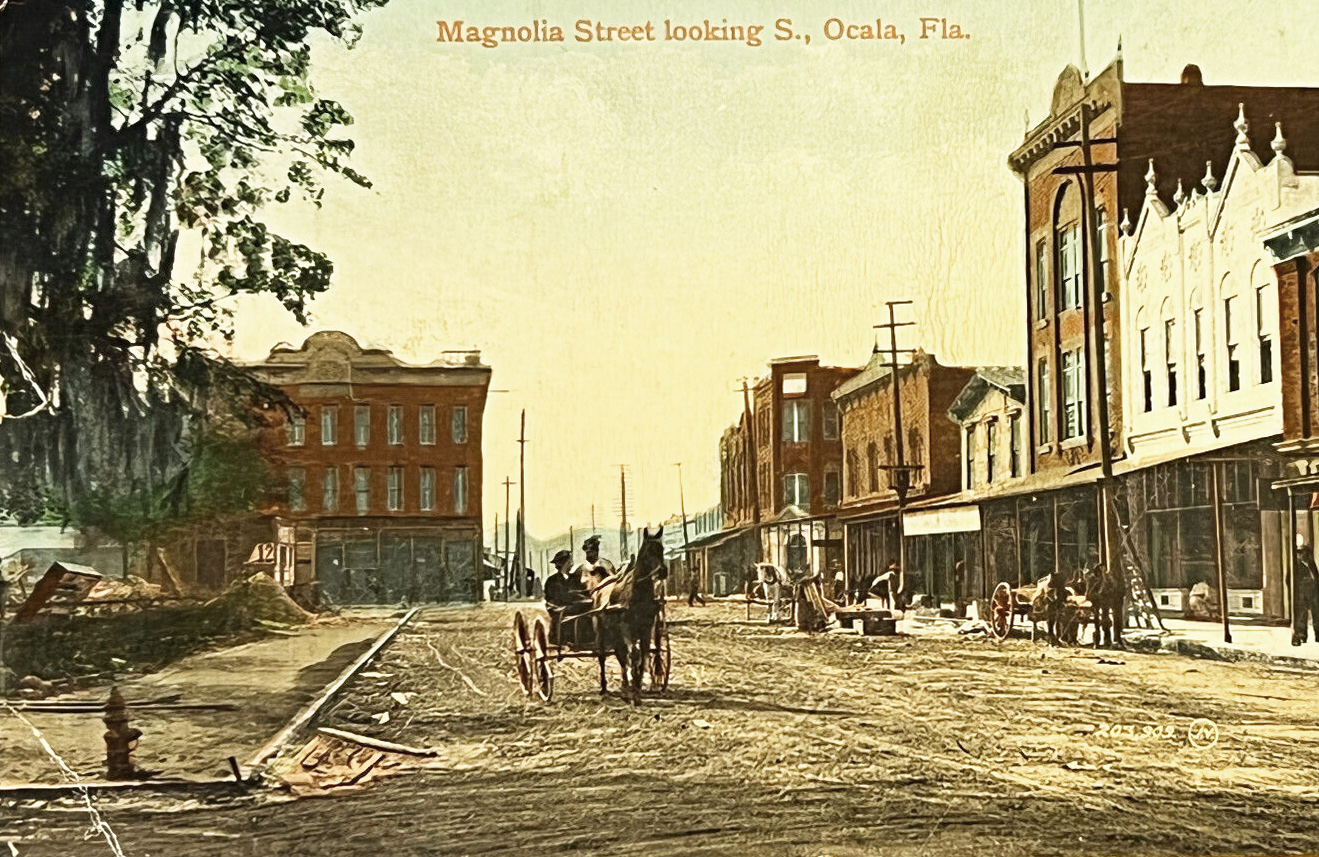

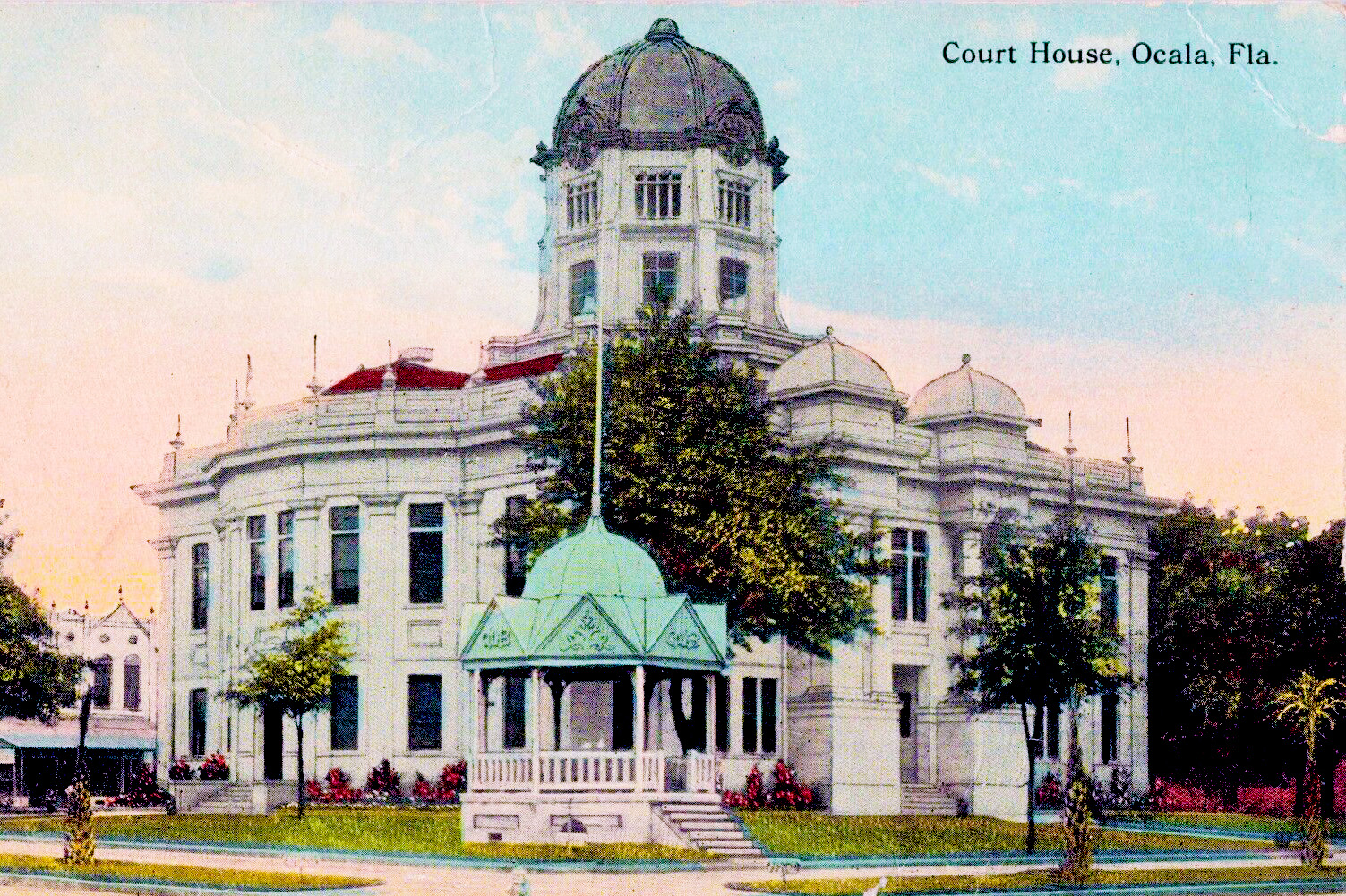

In the 1820s, during the Second Seminole War, the land became the site of a military outpost called Fort King that was used to repel incursions by Seminoles. It became a bustling hub for new settlers, as six military roads from all over Florida converged there. The fort was abandoned after the Seminole threat died down in the early 1840s and the settlers scrapped it for building materials. The creation of Marion County was recorded on March 14, 1844, and, in 1846, Ocala was appointed the county seat. One section was designated as a “public square” and was earmarked as the site of the first courthouse. Other plots were auctioned off and the first buildings included a store, a boardinghouse and the city’s first private residence. By 1847, a post office had been built and the city’s streets were being formally laid out. The settlement was described as having “the look of a rough-and-tumble frontier outpost, with dusty, unpaved streets.”

Ocala was officially incorporated in 1869, but the Civil War would bankrupt and nearly decimate the city—the population dropping from about 600 to 200 residents. But the city fought its way back and eventually became one of the most prosperous in Central Florida. By the early 1880s, “Ocala had become the largest commercial and trading point in the interior of the state,” according to the book Ocali Country – Kingdom of the Sun. Of course, it wasn’t called that yet. This particular moniker was the invention of the Marion County Chamber of Commerce, first coined as the county’s slogan in a chamber publication in 1925. You can still find historic postcards and brochures bearing the slogan for sale online. The idea was a phrase to promote Ocala’s “beautiful, year-round weather, warm mild winters, abundance of sunshine and agricultural development.”

The area quickly became the hub of a rapidly growing state, with sugarcane, tobacco, turpentine, cotton, rice, citrus, cattle and timber becoming important sources of revenue. The city consisted of a sprawling 80 blocks around a public square, with mostly wooden structures ranging from homes and businesses to hotels. The arrival of the railroad guaranteed that all of the area’s crops would reach larger markets and helped establish Ocala as a destination for travelers drawn here by advertisements professing the “health benefits” of the climate.

But on Thanksgiving Day in 1883, tragedy struck and Ocala was devastated by a fire that began in the city’s center and quickly spread. The inferno consumed buildings over an area of about five blocks and claimed the courthouse, five hotels and the principal businesses on the east side of the city. After nearly two decades of growth, the community was facing a hard road to recovery. But in a literal “rising from the ashes” scenario, Ocala’s downtown district was quickly rebuilt using materials like iron, stone and brick, instead of lumber. Which brings us to the third and most enduring moniker: Brick City.

The swift rebuilding of the city, fueled by investors, taking advantage of actual “fire sale” prices, was heralded as a rebirth and the reconstruction was completed by 1888. The population had risen to 2,904 at the end of the decade.

This Thanksgiving Day marks the 135th anniversary of the fire. Each year, the city holds an annual celebration that blankets downtown with a blazing canopy of lights that one local journalist reported looks to be “lit as if by flames” and has the “ironic title” Light Up Ocala. The event was first held on Friday, November 30th, 1984—exactly 101 years and one day after the fire of 1883. This year, the kickoff will be on Saturday, November 18th.

Making Moves

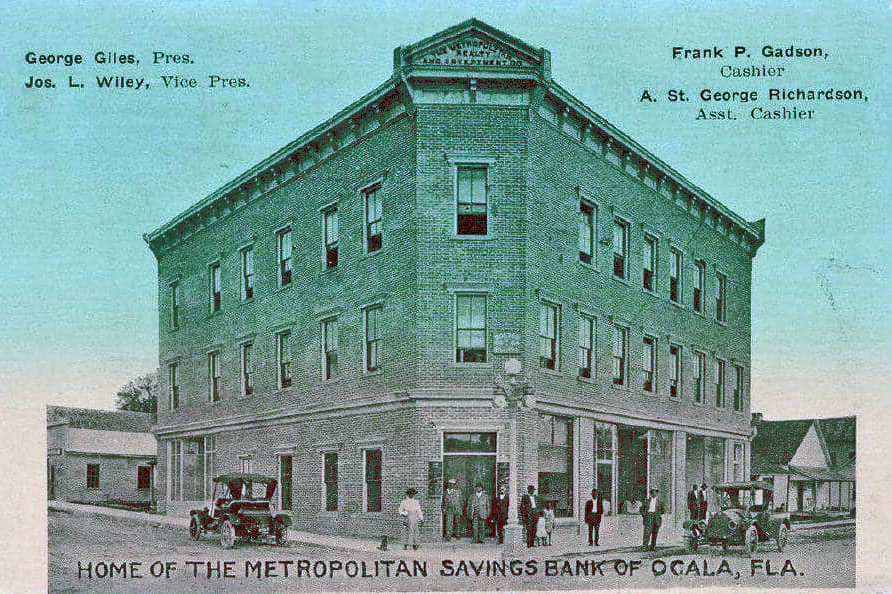

By the 1880s and 1890s, Black Ocala residents rose to prominence as successful merchants in the city, owning and operating a number of downtown businesses. Blacks also held key roles like Treasurer, Tax Collector and member of the Board of Aldermen. Black residents also led the way in such fields as medicine, banking and technology. By 1914, Black residents of Ocala and the surrounding areas were said to be the most prosperous Blacks in the South. They owned most of the businesses on West Broadway, from Magnolia Avenue to 16th Avenue, as well as the majority of businesses on Magnolia Avenue from Broadway south to 10th Street and on South Main Street. Locals referred to the area as Black Wall Street.

That’s Entertainment

That’s Entertainment

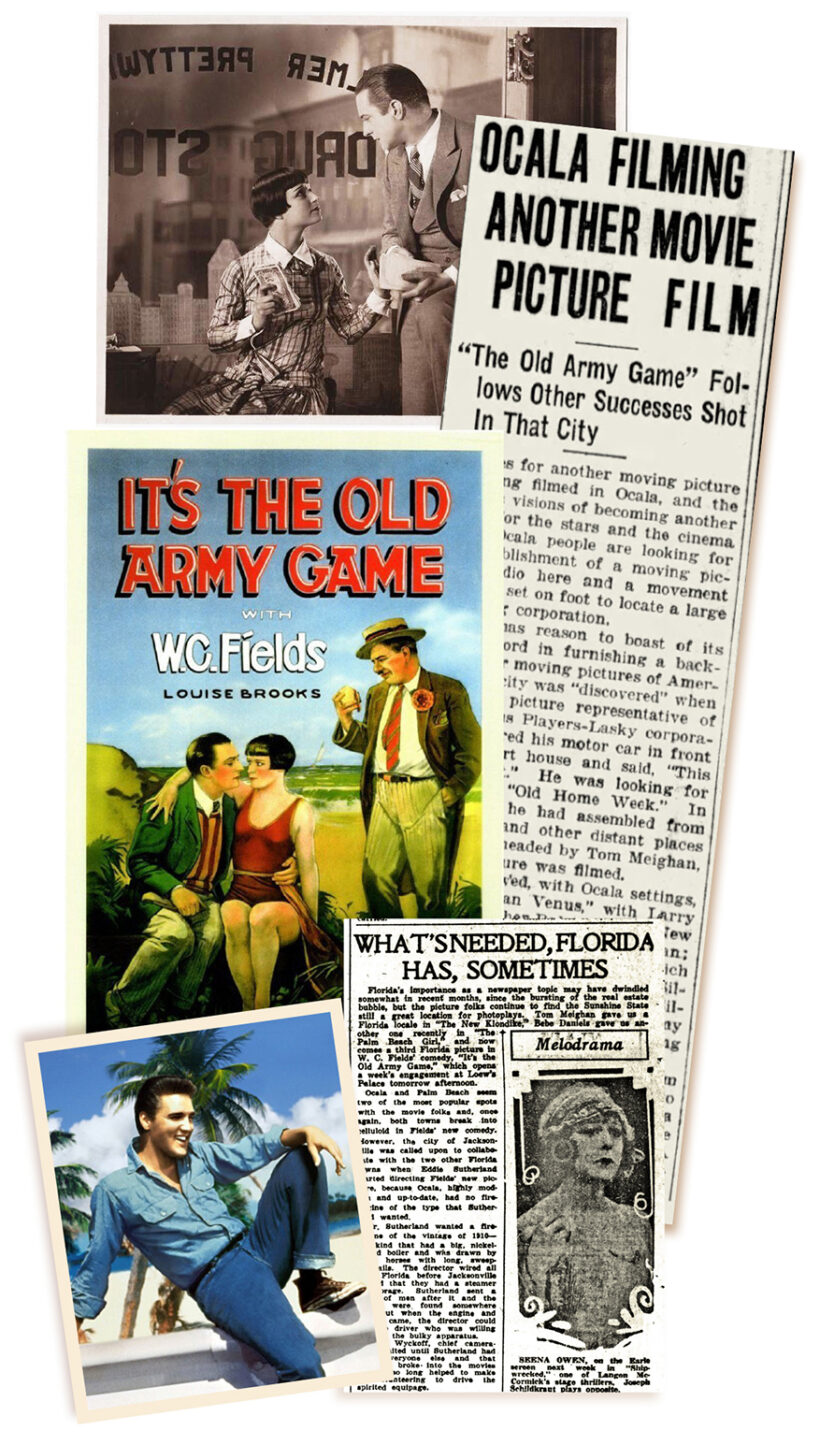

The 1920s brought a mixed bag of developments. Movies began to be filmed in the city, including The New Klondike in 1925, which was about the great Florida land boom that had inspired optimism in Ocalans and progress in terms of public works projects and private development. The boom itself failed to have a significant impact on Ocala, but the film industry was putting the city in the right frame. Newspapers as far away as Washington, D.C., ran articles on productions and two legendary talents, W.C. Fields and Louise Brooks, were soon in residence making the silent movie The Old Army Game. The film was the sixth to be made in Marion County by that point and it gave locals hope that Ocala might become the Hollywood of the East. In one of his columns, Cook reported, “The Marion County Chamber of Commerce was fired with new ambition to turn Ocala into ‘The Keystone City.’”

And while that particular nickname didn’t take off, and the building of a film production hub here did not happen, hundreds of movies and TV shows have been made in Marion County. Even Elvis drove locals to previously unseen heights of distraction when he filmed part of Follow That Dream in downtown Ocala in 1961.

Changes Afoot

Changes Afoot

Following the stock market crash of 1929, the city experienced financial troubles. Independent merchants struggled to stay in business and faced competition from chain stores.

And while recovery from the economic hardships of the Depression was slow, by 1940, more buildings were being built in Ocala’s business district than at any time in nearly half a century, including downtown’s iconic movie palace The Marion Theatre, which may be Ocala’s most photographed downtown building and is an enduring symbol of the optimism of that period.

Unfortunately, the time also marked a phase when grand historic buildings had what was deemed “meaningless ornamentation” removed to make them feel more modern. Many of the brick facades that had defined the city were altered with stucco or cement in favor of mid-century styling. Some of the older, landmark buildings were even torn down to make way for more contemporary architecture. “Brick City” references began to fade during this time.

A few years earlier, in 1936, Carl Rose established Rosemere Farm, the first thoroughbred operation in Marion County, beginning Ocala/Marion County’s thoroughbred industry. When Florida-bred Needles won the Kentucky Derby in 1956, it put Ocala on the map as a major player in the horse breeding game.

The fifth moniker, “Horse Capital of the World,” grew out of that success and was established in 2001 when The Florida Thoroughbred Breeders’ & Owners’ Association trademarked “Ocala/Marion County: Horse Capital of the World.”

A “Walk of Champions” that highlights some of the most famous equine champions from the area is coming to downtown in late summer/early fall. The Ocala/Marion County Chamber & Economic Partnership has been working with the FTBOA and the Ocala/Marion County Visitors and Convention Bureau on placing 24 bronze plaques on the sidewalks both in front of Mark’s Prime Steakhouse and the Hilton Garden Inn on the square.

A Turning Point

In 1965, “Courthouse Square” became just another square when a wrecking ball leveled Ocala’s beloved 1906 courthouse—the final of three that had once occupied the space, based on the city’s original plan. Its massive clock and bell were removed and are now on display in the lobby of the current courthouse. It was just the latest in the losses, but it signaled entry into a period that would be marked by a lack of vision and a series of well-intentioned missteps.

Downtown Ocala had suffered more than just a loss of history—it was losing its purpose. Cook chronicled that, by 1967, Ocalans were proposing drastic action to save the downtown commercial area from what he called “accelerating decline as more businesses moved into outlying shopping centers.” One of the possibilities was building a mall downtown, another proposal was for an underground parking garage to serve existing businesses and perhaps stimulate new commercial activity. But these projects were deemed wrong for the district and too costly. And still, even the remaining merchants felt they could not continue to do business downtown without a solution to the parking problem.

But things would need to get worse before they got better. And it would take until the 1980s for the district to get back on track. In 1980, HOPS was established and has since saved dozens of historic properties from demolition and helped pave the way for revitalization. One of their first steps was to work on the creation of a replica of the original 1880s bandstand, often called “the gazebo,” that now serves as the centerpiece of the downtown square, as well as a symbol of Ocala’s history.

But things would need to get worse before they got better. And it would take until the 1980s for the district to get back on track. In 1980, HOPS was established and has since saved dozens of historic properties from demolition and helped pave the way for revitalization. One of their first steps was to work on the creation of a replica of the original 1880s bandstand, often called “the gazebo,” that now serves as the centerpiece of the downtown square, as well as a symbol of Ocala’s history.

Over the course of several decades, the community, the city and some visionary business leaders worked together to chart a steady climb toward reestablishing downtown as a place that was full of promise. There was renewed interest in the restoration of treasured buildings and strategies to attract businesses and patrons back downtown, with places like Harry’s Seafood Bar & Grille bringing new energy to a familiar old haunt when it took over the space in 1987.

In recent years, a lot of that progress was made by getting back in touch with Ocala’s storied past and leaning into a distinctive vintage-modern, sophisticated yet rustic aesthetic that ties venues like Ivy on the Square, Harry’s, Brick City Southern Kitchen and the Anti Monopoly Drug Store speakeasy into a story that is bigger than any one business but speaks to Ocala’s rich history. On the other side of the coin, there are places that have a distinct vibe of their own, from Bank Street Patio Bar and Sayulita Taqueria to The Tipsy Skipper and The Courtyard on Broadway.

Today, downtown is a charming, walkable area that is home to an eclectic blend of shops, restaurants, coffee houses and lounges, hotels, professional offices, salons and antique stores. It also has an impressive number of public art projects and murals, as well as being a venue for regular street festivals and public events. The square serves as a popular gathering place and the gazebo often hosts live music performances.

On The Rise

The city has lots of exciting changes on the way. There are several new hotel projects that have been creating buzz, most notably the renovation of the historic Marion Sovereign Building (once home to the Marion Hotel), which local philanthropists and developers David and Lisa Midgett are transforming into a boutique hotel with high-end amenities and a rooftop bar.

Like many historic downtown buildings, the 1927 Mediterranean Revival hotel fell into disrepair in the 1970s and ’80s. The facade will be “restored and repaired” to bring back its original grandeur. The hotel is projected to open by Christmas of 2024.

There also will be a second public parking garage constructed at the current site of the Mount Moriah Missionary Baptist Church on Southwest 3rd Avenue.

And there will be even more great eats on offer with a new spate of eagerly awaited restaurants including District Bar & Kitchen and Mellow Mushroom opening.

The evolution of downtown is not the full story of Ocala’s origin or growth, but it is an integral part of the tale and the city’s historic square is at its heart. You can’t walk the streets of downtown and not marvel at the history, observe the progress the community has made in establishing a vibrant destination for visitors, be inspired by the current efforts at revitalization and feel the excitement for what is on the horizon.

So, if you haven’t lately, just like that old song says, you should “go downtown—everything’s waiting for you.” OS