Cruising along wide interstates, touring the state’s tourist attractions and shopping in air-conditioned malls, it’s easy to forget that Florida was once a rugged, dangerous, unexplored territory.

After the Spanish colonial period, the people who settled this intimidating, wild peninsula were a bit untamed themselves. Back in the day, the Sunshine State attracted a hardy, adventurous sort; it wasn’t unusual to find renegades and folks on the run from the law.

The first generation Florida Cracker was not a pillar of society. A life of hard knocks had not been a bad school, however, for it had taught both man and woman the skills they needed and given them the determination that was required to survive in this new life… Today, Cracker refers to the unpretentious people and architecture found on farms and in rural communities still sprinkled throughout these peninsular and panhandle wetlands.”

So writes Ronald W. Haase in his intriguing book Classic Cracker: Florida’s Wood-frame Vernacular Architecture.

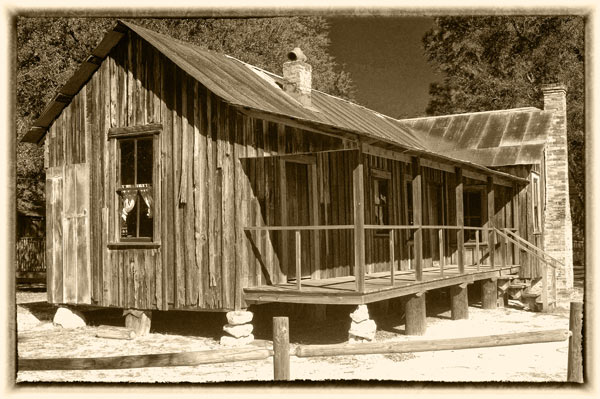

When these early settlers called themselves “crackers,” it was a reference both to the cracked corn they used to make cornmeal and to the cracking sound made by their long, leather whips as they drove cattle out of thick scrub and treacherous bogs where it was impossible to ride a horse. Their houses had distinct architecture still seen today and often featured the “dog-trot” style, in which two rooms are separated by an open breezeway and covered on both sides by a broad, shady porch.

Despite the rapid spread of progress and concrete, Florida has a number of people living the keep-it-simple cracker lifestyle… even in these days of satellite technology and the Internet.

Although Florida’s pioneers were forced to live off the land, today, we have the luxury of choosing our back-to-nature tasks, such as making bread, growing our own vegetables and herbs, raising livestock for meat, hunting, canning produce and jams or simply hanging clothes on a line instead of using a dryer.

While we are accustomed to buying almost everything we need, Florida’s early settlers worked from sunup to sundown just to survive.

“You look at old photos and those people were all skinny. That’s because they were working very hard all day,” observes Scott Mitchell, director of the Silver River Museum & Environmental Education Center in Ocala. “They’d grow cash crops like cotton and sugar cane to buy things they needed but couldn’t make themselves, like cast iron skillets and fabric. They’d also barter goods and services. They made cane syrup, which was where they got their sugar, and boiled down seawater to get salt.

“You might be surprised to find out that some of those old skills are still being practiced by someone you’re standing next to in the grocery store,” says Scott. “It’s interesting to find that, in 2012, some people are still living this lifestyle. Some do it for tradition; others just to stretch their dollars.”

Jim Carty does it for both reasons. A native of Marion County, Jim, 61, was raised on a dairy farm in Santos and has lived in this area his entire life. He doesn’t mind being called a “cracker.”

“Most crackers have a way of thinking and a lifestyle,” he says. “There’s nothing wrong with being called a cracker.”

Jim maintains a simple lifestyle, residing in an old tenant house (circa 1910) from his family’s dairy. It has no hot water heater or dryer, but he does have air conditioning. He heats his home with the fireplace, so his winter electric bills average just $25 a month.

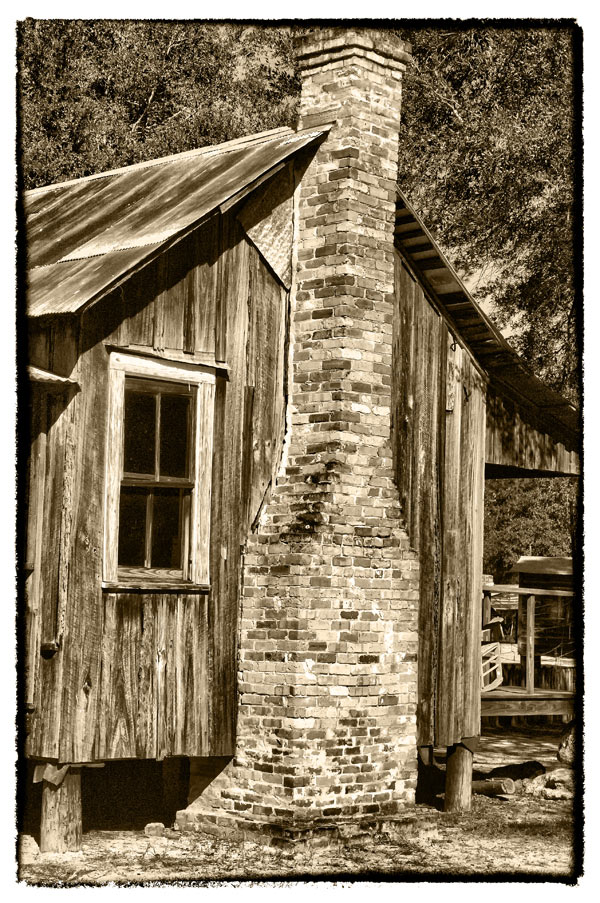

For fun, he built a cracker-style cabin with no electricity (think of it as a “cracker man cave”) on his property, using pine trees he cut down, milled and sawed himself. Resembling a structure from the late 1800s, it’s set on “lighter wood” pine posts, which are naturally bug-resistant and won’t rot.

“I just wanted to make something authentic to the period,” explains Jim, who can be found in the blacksmith shop and making cane syrup during the Ocali Country Days festivalheld each November at the Silver River Museum.

He finds it a little sad that so much of the American lifestyle is about convenience and immediacy.

“People get their paychecks and go buy what they need; there’s hardly anything you can’t find at Wal-Mart. The typical family—with both adults working two jobs—doesn’t have time to do all the stuff from scratch.”

Jim, on the other hand, grows a kitchen garden, raises chickens for eggs, does metal work in his blacksmith shop, makes cane syrup, repairs windmills, hunts deer and hogs, butchers his own meat and makes his own sausage.

He doesn’t have a computer, but he does have a cell phone. (During our interview, that phone rang and he retrieved it from the small pocket on the front of his denim overalls. “Bib overalls were way ahead of their time,” he grins. “They had cell phone pockets before we ever had cell phones!”)

Mike and Monica Carter enjoy a homestead lifestyle in an 1800s sawmill on the banks of Prairie Creek, east of Gainesville. Their fish camp at Newnan’s Lake has been in the family since 1961.

Back in the early 1990s, the Carters were raising their children in the most natural environment possible, but Monica was shocked to discover that didn’t extend to the bath and toiletry items they used.

“I began to realize our natural home included many not-so-natural products,” recalls Monica, who began research in earnest. “These products are full of chemicals I could not spell, much less pronounce. There were so many chemicals, and our bodies absorb 60 percent of what is put on the skin.”

So in 1995, she started making soap for family and friends. Today, Monica’s Cococastile Soap has become a favorite at local shops, farmers markets and festivals.

“We only use premium olive oil and coconut oil, so it’s a clean soap because it’s not made from waste oils,” she explains. “That way, you don’t have soap scum and it’s super bubbly. It lasts longer than regular soap, doesn’t clog pores, rinses clean and can be used for washing your hair, too.”

Lest you think all-natural products are a “shortcut” compared to mass-produced goods, consider the time Monica spends making her soap. Each batch takes six hours to make, then it’s in the mold for four days and cures on the shelf for another 30 days.

“Like a fine cheese, it takes time,” she says. “We keep the soul in the soap!”

The Carters regularly sell their soap products at the farmers markets in Gainesville and Ocala, the same places where they buy much of their produce and food products and shop for handmade items.

After all, that’s what the cracker lifestyle is really about: keeping it down-to-earth, being as self-sufficient as possible and sharing your knowledge and skills. The world would be a better place if more people did the same.

Want To Learn More About The Cracker Lifestyle?

Scott Mitchell of the Silver River Museum recommends:

Cracker: The Cracker Culture in Florida History by Dana Ste. Clair

A Land Remembered by Patrick D. Smith

Ocali Country Kingdom of the Sun: A History of Marion County, Florida by Eloise Robinson Ott and Louis Hickman Chazal

Classic Cracker: Florida Wood Frame Vernacular Architecture by Ronald W. Haase

Where To Find Cracker-Style & Natural Products

Ocala Farm Market On the downtown square. Saturdays 8am-1pm

Union Street Farmers Market At the old Courthouse downtown on University Avenue in Gainesville. Wednesdays 4-7pm

Prairie Creek Soap Works soapmakermonica.com