Adrenaline junkies. Thrill seekers. Risk takers. Those who pursue dangerous sports, hobbies or professions go by many names. For this group of Ocala-area men, what they do that most wouldn’t is about many things, mostly adventure and passion rolled into one, sometimes bordering on obsession. Given that, although they are bold souls, they are not foolhardy ones. They train for years for proficiency, stressing safety for themselves and others.

For these men, dangerous pursuits are not just a one-time rush—they’re a way of living.

Art Shaffer, Skydiver (Pictured above. Photo by Shane Shaffer)

For Art Shaffer, skydiving is a leap of faith—an apt description for stepping out of a plane on purpose at altitudes of 13,500 feet and more, then free-falling at 125 miles an hour for a minute or more before deploying the parachute. The faith part? Trusting that the parachute will open and you’ll land safely.

“When you think about it, skydiving is not a natural thing to do,” says Shaffer, 49, a master professional skydiver who owns and operates Skydive Palatka. “But it’s an amazing way to be a part of nature. I don’t think of it as falling through the sky but more like surfing on the air currents in the sky.”

Shaffer was hooked on skydiving’s adrenaline rush from his very first jump at 22. The Gainesville native was attending the University of Florida when he heard about skydiving at the Williston Airport. A lifelong sportsman, Shaffer thought that might be fun.

“Right in the middle of that first solo jump,” says Shaffer, “I got the feeling that skydiving was something I was going to be doing for a long time.”

Since that first jump 27 years ago, Shaffer has logged 13,000 jumps and counting. He quickly became a certified instructor he says “to subsidize my own jumping.” In 1992, Shaffer was part of a team of 200 skydivers that set the then world-record for a spokes-concentric formation. Also that same year, he was part of a 100-member team that set an unofficial record of making back-to-back formations. Formation jumps are generally made from 19,000 feet, allowing for the skydivers to join up during 60 to 70 seconds of freefall.

Although not considering himself a daredevil, Shaffer admits that some of his skydiving endeavors would make people want to call him one. In addition to the risky formation diving, Shaffer headed his own Art of Skydiving demonstration team for several years.

He also tests and trains military skydiving equipment for a military contractor. The assignments take him to military bases in and out of the country, being the first to try out new skydiving equipment. Once the equipment passes the tests, Shaffer trains the military personnel in its use.

“It’s something I enjoy doing, and it’s a challenge,” says Shaffer, whose skydiving injuries over the years include a broken ankle, pulled back ligaments and several cracked ribs. “I put safety first and remember that stupidity and the ground hurt.”

Shaffer has lost many skydiving friends over the years, including witnessing from the ground an in-air collision between two divers in 2007. Shaffer’s longtime friend, Bob Holler, was killed. According to the United States Parachute Association, there were 21 skydiving fatalities from an estimated three million jumps in 2010. To date, six skydiving deaths have been recorded in 2011.

“I guess some people think that skydiving is a dangerous sport,” says Shaffer. “But the way I look at it, life is dangerous and dying is just part of life. That doesn’t mean we stop enjoying life.”

It’s the enjoyment of skydiving that Shaffer wants those who come out to Skydive Palatka for a tandem jump to experience. From Thursday through Sunday, Shaffer and his team take clients 18 years old and up on tandem jumps. Shaffer, who usually does 20 to 25 jumps over the three-day stretch, has many regular clients of all ages, including several in their 80s and 90s.

“For a lot of people, skydiving is about facing your fears,” says Shaffer, “and taking that leap of faith.”

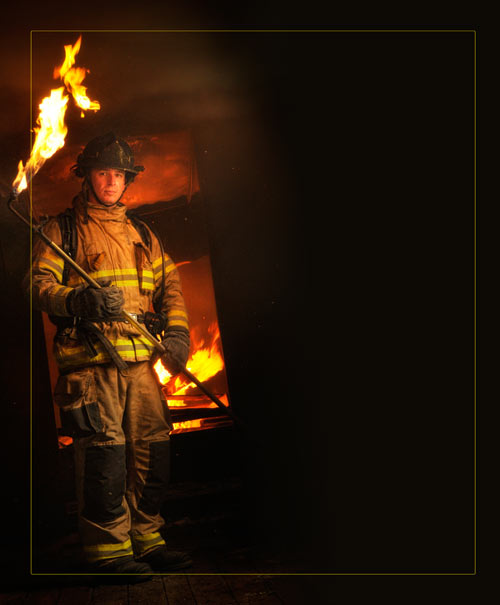

Richie Lietz, Firefighter

Call it knowing the enemy. And in Richie Lietz’s world, the enemy is fire, and he knows it well. As an Ocala Fire Rescue firefighter, Lietz battles blazes. But as the lead live fire-training instructor at the Florida State Fire College, Lietz sets fires. The latter could be seen as a necessary evil—to slay the fire-breathing dragon, you have to know the beast.

Photograph by John Jernigan

“Live fire training is absolutely necessary,” says Lietz, 36, who has been a firefighter for 11 years. “This type of training gives us the opportunity to understand fire dynamics in the safest environment possible. Training helps you prepare physically and psychologically to deal with the challenges of fighting fires. If we do it right, the training automatically takes over in the real world.”

Fire fighting is a dangerous profession and so can be the training. According to the U.S. Fire Administration, approximately 100 firefighters are killed while on duty, with six percent of those deaths during training.

“Safety comes first in the field and in our training,” says Lietz. “We very carefully plan out every live fire exercise and preach safety to our trainees. If we don’t stay safe, we can’t help other people.”

It was the desire to help others that led Lietz, a Vanguard High School graduate, to become a professional firefighter.

“Growing up, I remember watching the TV show Emergency and running around in a fireman’s helmet,” says Lietz.

After first completing the EMT training, Lietz then attended the Florida State Fire College and graduated in 1999. He didn’t have to wait long to battle a fire.

“It was only my first week on the job and we got a call on a structure fire,” he says. “I remember it as clearly today as the day it happened. It was definitely a rush, and I knew I had made the right decision.”

Being so sure of the decision to become a firefighter soon had Lietz wanting to help others training to join the ranks. For the past five years, he’s been a live fire instructor at the Florida State Fire College. Located northeast of Ocala on County Road 25A, the FSFC is a regular campus with classrooms but also with live fire training facilities. Almost like a Hollywood movie set, props like buildings, cars, towers and pits are used in the live fire training. The training teaches how to make critical decisions in dealing with flames, intense heat and smoke while wearing 90 pounds of gear.

For safety reasons, the buildings on the FSFC are engineer-designed simulated structural fire buildings equipped with computers. These control built-in fire-producing devices that run on propane, allowing instructors to select how the fire will burn and at what temperatures. In an emergency, the burn buildings have a computer-operated system to extinguish the fire and extract the smoke.

“The trainees really get excited about the thick black smoke,” says Lietz. “Getting charred debris and soot on their helmets is kind of a rite of passage.”

In addition to the live fire training on campus, acquired structures, like abandoned buildings and cars, off campus provide for a different kind of training. And because these structures provide a less controllable real-life fire scenario, an extensive safety preparation checklist is followed. Manually administered propane is used to set the fires in acquired structures.

“One of the best live fire training sessions I ever had was a three-story apartment building that was donated,” says Lietz. “We prepped it, then burned it room-by-room. By the time we burned it to the ground, we had learned a lot about fighting fires.”

Bill Foote, Cave Diver

Bill Foote was in trouble. Halfway through a complex cave dive, more than a hundred feet below the surface, his underwater motorized scooter malfunctioned.

“It was a serious equipment failure at the most inopportune time,” recalls Foote, who at that point had already logged 20-plus years of diving. “I had a 50-50 chance of making it out alive.”

Ironically, Foote and his two buddies had opted to use scooters because of the especially challenging cave dive. This particular underwater cave system in north Florida was a series of tunnels connected by shafts reaching a depth of more than 180 feet. The scooter would allow the divers to more quickly navigate the distance and currents than on their own power.

“The scooter restarted, and we turned around, but now I’m going against the current,” says Foote. “The scooter would stop then start, stop then start. All of this time, I’m using up lots of air. I was very relieved when I finally made it to the surface.”

When Foote checked his air tanks, one was empty and another was dangerously low. Even his decompression tank was low on oxygen. During the dive, Foote remained calm, and his extensive cave dive training automatically took over. He lived to tell of another diving adventure.

Although Foote has been a certified diver and diving instructor for over 40 years, he is especially intrigued by cave diving, exploring what he describes as “cold, dark scary places, these underground rooms full of cobalt blue water and unseen treasures.” And Foote was in the right place, as north-central Florida is the world’s leading cave-diving destination thanks to the Floridan Aquifer.

In the mid-1980s, Foote headed up a diving team that included a photographer, cartographer, biologist and archaeologist to map the Silver Glen Springs cave system. The team received a special permit from the U.S. Forest Service for the two-year project in the Ocala National Forest.

Certified by multiple major diving organizations, Foote’s diving résumé is extensive. He’s recorded more than 3,000 dives; he’s been involved in scuba diving film projects, as well as cave-diving exploration, mapping and documentaries. Foote has trained more than 1,500 divers, including the members of the Marion County Sheriff’s Office Recovery Team. So when Foote talks about cave diving, people listen.

“Cave diving is a much more dangerous and technical form of diving than open water diving,” says Foote, 55, who has owned and operated Ocala Dive since 1992. “It’s an overhead environment, meaning you have the cave ceiling to deal with. You are beyond the surface air and light, so you have to depend on the artificial air and light you carry with you. There are currents to deal with, and if sediment gets stirred up, your visibility is greatly reduced. It can be a very unforgiving environment.”

How unforgiving? According to International Underwater Cave Rescue and Recovery, there have been more than 375 cave-diving deaths in Florida from 1960 to the present.

“Cave diving is a calculated, acceptable risk if the diver is properly trained, properly equipped and uses good judgment,” says Foote.

“Cave-diving training is as complex as the cave diving itself,” adds Foote, who teaches both open water and cave diving. “You have to be very disciplined in your training, planning and actual diving. A very small percentage of people have the psychological mindset for cave diving.”

Count Foote among that elite percentage.

Sonny Tripi, Storm Tracker

If self-taught storm tracker Sonny Tripi tells you dangerous weather is coming, heed his warning. Not only does Tripi have an affinity for stormy weather, it apparently has one for him as well.

Photograph by John Jernigan

“My family and friends call me Mr. Lightning,” says Tripi, 52, who with wife Bonnie moved to Ocala eight years ago. “In my life, I’ve had at least 10 very close calls with lightning.”

Over the years, lightning strikes too close for comfort have scared the daylights out of Tripi on basketball courts, golf courses, in his house and car. Once when arriving home during a storm, lightning struck Tripi’s car antennae while he and his wife were still in the car. After the blinding white light and explosive boom of the strike subsided, Tripi opened his eyes to see all the instrument lights on the dashboard blinking and the melted antennae glowing red.

“When we went inside, we realized the lightning had hit the car antennae then gone through the house,” recalls Tripi. “It took out the TV, the appliances and our garage door opener.”

Tripi later sold that car, then one year later to the day, the new car also got hit by lightning while parked in the driveway. “The insurance company couldn’t believe it had happened again,” says Tripi.

Tripi’s passion for stormy weather began at a young age. He reportedly loved storms even as a baby. Tripi briefly took some meteorology classes, but then he got married and started a family, opting to forego the formal education. But he never lost his fascination, immersing himself in learning everything he could about the weather.

“I’ve always been intrigued by weather and how storms take on a life of their own and how insignificant we are to Mother Nature.”

Just this spring, tornado-producing storms killed more than 300 people in the South and Midwest. Florida’s spring and summer months are extremely active, and Tripi spends a lot of time on his two computers, tracking potentially dangerous weather situations. With Tripi in Ocala and fellow storm trackers Stephen Sponsler in Cape Canaveral and Jason Weingart in Daytona Beach, the trio has formed a severe weather-watching triangle. All three will head outside to storm track, cameras and video cams in hand.

“The three of us pretty much have this area covered,” says Tripi, “and we can send out alerts via Facebook, e-mails and texting. We also contact the National Weather Service and other agencies if we think we’ve spotted something significant.”

One of Tripi’s favorite places to track storms is the Ocala International Airport because of its location and the flat terrain. He says “you want to be able to see what’s coming and have time to get out of harm’s way so you can alert others.” Tripi has spotted tornadoes and felt the fury of an approaching storm but always keeps safety in mind for himself and others.

Although Tripi says everyone doesn’t have to be as an obsessive storm tracker as he is, he does think everyone should have a weather radio.

“It’s a $29.95 investment that can save your life,” says Tripi.

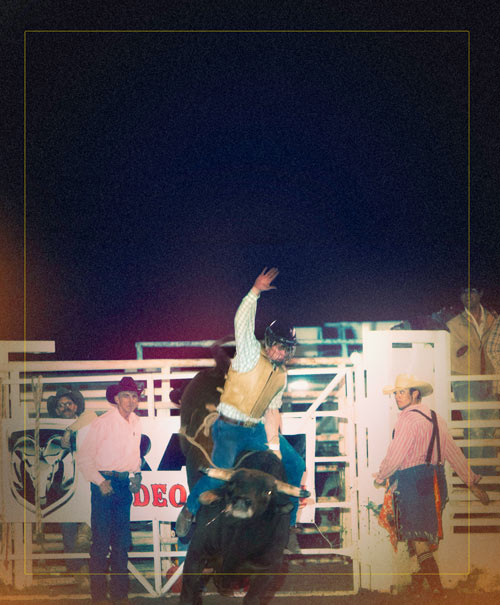

Corey Ferguson, Bull Rider

Eight seconds. That’s how long a bull rider has to stay on to earn a score. Doesn’t seem like that would be a problem, does it? Except that bull riding is called the most dangerous eight seconds in sports.

Photograph by Ron Mandes

Every year, the U.S. professional rodeo circuit averages one or two deaths from bull riding. Then there’s hundreds who are hurt each year, some suffering serious spine or brain injuries, according to the World Health Organization. Protective vests are now mandatory, while a riding helmet with a wire face mask is still optional. The most common causes of bull-riding deaths and injuries are from being gored by the bull’s horns or trampled. Think of first being hit by a two-ton pickup truck, then run over by it. It’s no wonder bull-riding accidents are called “wrecks” in the rodeo world.

But ask any bull rider why he’s involved in this dangerous sport and he’ll tell you that he loves it. Corey Ferguson, a 21-year-old Micanopy cowboy, is no different.

“It’s a challenge like no other,” says Ferguson, who rode his first bull at 14. “It’s you against the bull, and you have eight seconds to beat him. Yes, there’s that adrenaline rush, but it comes after the ride. During the ride, you need to be calm and relaxed, reacting to the bull’s moves.”

Ferguson, who grew up around cattle and was breaking horses before he was a teenager, didn’t plan on being a bull rider. The self-professed “wild kid who was probably headed for big trouble” was steered, pardon the pun, in that direction by, of all things, a rodeo clown. Micanopy resident Cliff “Hollywood” Harris, who performs at rodeos with his son Brinson, aka “Boogerhead,” took a special interest in Ferguson.

“Mr. Cliff could tell I needed some direction or I was going to get into a lot of trouble,” says Ferguson. “He tried to get me interested in baseball, basketball and football. But when he suggested I try bull riding, my eyes lit up.”

As fate would have it, Ferguson won the first junior bull-riding event he entered. After winning that initial bull-riding belt buckle, Ferguson was hooked. Soon, he was going to rodeos every weekend, eventually competing on the Southeastern States Bull Riders Circuit. His long-term goal is to compete on the national Professional Bull Riders tour.

Ferguson favors bulls with what is called in rodeo lingo as a “wild Western style of bucking.” This type of bull, according to Ferguson, “will jump high, like six feet, and that gives me time to get a good hold of my rope, spur, and be set for a spin.”

In bull-riding circles, there’s a saying: It’s not if you’ll get hurt, it’s when.

This past spring, Ferguson had two first-hand experiences of that unfortunate, but all too true, prediction. First, he severely hyper-extended the left elbow of his riding hand. Then, two weeks later, he broke the tibia just above the ankle of his right leg.

“It’s all part of the game,” says Ferguson, who expects to be in an air cast and on crutches for three months. “I’ll heal up and be back on a bull soon because I love it.”