A single spotlight pierces the velvety blackness of the stage, revealing a beautiful woman. Suddenly, she is not alone. A startlingly beautiful gray Arabian stallion walks into the pool of light, materializing from the darkness as he approaches the woman. His delicate muzzle touches her offered hand in silent greeting.

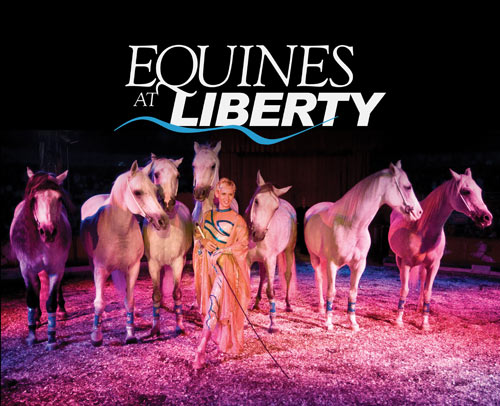

Moments later they are joined by more horses, until eight horses—all in varying shades of gray and cream colors—have formed a loose circle. Despite the audience of thousands, each horse’s attention is unwaveringly centered on the woman. Eight pairs of dark, luminous eyes focus on her. There is a palpable sense of strength and energy awaiting release.

The blonde turns and steps back, deftly motioning with one hand. Her body language, while almost imperceptible to the mesmerized crowd, is like a shout to the horses. As one, they spin and whirl into a tight circle, galloping around the woman, thick manes and tails waving, an exercise in controlled power and beauty.

Over the course of 20 minutes, the horses perform remarkable feats of synchronized movements. There are no lead lines, no bridles, not one bit of equipment directing them, which is what liberty work is all about, only the slim blonde in the gauzy costume, who commands their attention with both ease and grace.

The crowd has been treated to a liberty demonstration without equal, and they know it. Sylvia Zerbini and her horses leave the stage to a thunderous standing ovation.

A Florida native, Sylvia hails from a nine-generation circus family and has been performing since the age of 13. Her father, a native of Italy, and mother, a native of France, immigrated to the U.S. in the early 1960s. While her father trained horses and wild animals, her mother was an aerialist, or trapeze artist.

Born in Sarasota, Sylvia studied ballet and gymnastics and performed on the trapeze from an early age. She doesn’t remember a time when her family did not have horses.

“Horses have always been my love,” she says. “My first was a Shetland pony named Silver I got when I was 5 years old. I taught him all kinds of things; he could lay down, bow, and I could run up behind him and jump on his back like the Lone Ranger.”

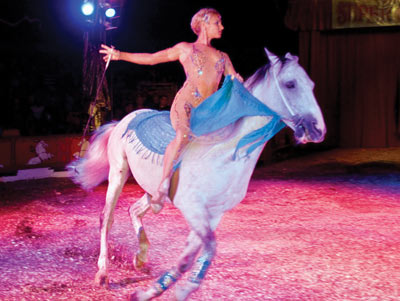

Sylvia was one of the first people to mix aerial trapeze work with horses in performance. She’s won numerous awards for her acts, including the prestigious Cup of Monaco, presented to her by Monaco’s prince rainier. If you visit the Circus Hall of Fame in Sarasota, you’ll see the star honoring her work.

Now, after four incredibly successful years of touring with Cavalia, the highly acclaimed equestrian spectacle, from 2008 through August 2011, Sylvia has come home to Ocala to move her career in another direction. She had been deluged with requests from horse owners around the country asking if she could teach them how to do liberty work. In addition, Cavalia had made a commitment to tour in China, and Sylvia was concerned about possible travel restrictions on her stallions returning to the U.S.

This past August, with the encouragement of Richie Waite, her husband and business manager, she left the show to focus on giving liberty clinics and teaching private liberty lessons.

“Cavalia was beautiful and a great production to be with,” says Sylvia, who had made a name for herself long before she joined the traveling equine show. “Now I’m at a place where I want to do what’s good for my horses and to set the rules. I want to help educate the equestrian world on the ABCs of groundwork.”

Part demonstration, part instruction, Sylvia’s clinics, which are held at equine facilities across the U.S. and Canada, begin with a 30- to 40-minute demonstration, much like her performances with Cavalia.

The big difference is she’s now playing to an audience of horse people who truly appreciate the amazing things she does with her equine partners. Clinic attendees are typically horse owners who want to create stronger bonds with their horses and learn how to work them at liberty. After giving a demonstration showing what horses can do at the top level of liberty work, Sylvia proceeds to break things down and explain to the attendees exactly what she does. During her clinics, she not only demonstrates with her own finely tuned horses but also works with horses that have less training, and even with horses she’s never seen before.

“It’s all body language. For example, the position of your shoulders either puts pressure on the horse or takes it off,” Sylvia explains. “When you pay attention to your body language and placement, the horse more easily understands what you’re asking. We just need to explain it better and look for the signs the horses are giving us. I call it the ABCs because once you have that bond and connect with them, they’re so willing. Everything else falls into place.”

Many horse owners get frustrated and think their horses are trying to “test” them or “pull a fast one.” Sylvia disagrees, explaining that when a horse won’t do what you ask, it’s simply because it doesn’t understand what you’re asking.

Once the person alters his or her mental approach and considers how the horse interprets things, the whole picture changes.

By its very nature, liberty work allows the horse the option of leaving, and he definitely knows this. Yet the bond the horse has with its handler causes it to look to that person for direction and security. Plus, as Sylvia explains, when it’s fun for horses, they want to cooperate and be part of the action.

In the Cavalia show, Sylvia’s horses came out onto the stage before she appeared. As soon as she entered the stage, all the horses immediately came to greet her. Yet, that was never something she taught them. They were simply eager to see her and knew that whatever came next was going to be interesting and fun.

In several performances, one of her young stallions Tonner decided to gallop in a more direct line to a certain part of the stage. Obviously, in a liberty performance, he could do whatever he wanted. But when he looked over and saw the rest of the horses gathered around Sylvia, he quickly decided that was the better place to be. With no cue from her at all, he galloped around and rejoined the other stallions. The audience had no idea the horse’s actions weren’t a choreographed part of the performance.

“My horses surprise me every time I work with them,” says Sylvia. “They blow me away by the way they communicate. You have to be paying attention, and your mind has to be totally into what you’re doing, because if you’re distracted, the horses will let you know it.”

Working with a single loose horse in a quiet corral is one thing. When Sylvia’s performing in front of thousands of people with eight to 10 horses at once, it’s an entirely different scenario.

Or is it?

Not really, she explains. The secret is that she’s already built a bond and understanding with each individual horse. As she puts it, she “makes good memories” for them. Each gesture, each body movement, each spoken cue means something specific to the horse.

Sylvia teaches her horses in French.

“My father always trained in French. The tone is calmer, and the words are more like singing; they just roll off your tongue,” she says. “You want to keep your vocabulary very short; I try not to use more than seven different verbal cues so they understand each word and what it means.”

Although there’s plenty of psychology involved in what she does, Sylvia says it never feels like “work.” When she’s training a horse, the moment the animal responds positively, she rewards it with the verbal cue, as well as a scratch or rub. This is the foundation for “making good memories.” At times, she also rewards them with a treat. Once the horse understands what the verbal cue means and that it’s connected with feeling confident, relaxed and safe, it never forgets.

“When the horses go on stage, they’re feeding off the energy from the audience. I bring them back to me because I’m their comfort zone, I’m their good memory,” says Sylvia.

“Horses are good at maintaining good memories,” she adds. “If you have a horse that starts to panic and you give the verbal cue you use when giving them a treat, you can literally interrupt a potentially bad situation with a verbal cue attached to a good memory.”

Sylvia says that once her horses know a routine, she doesn’t continue to practice, as that will make them dull and bored. For that very reason, she never duplicates backstage what she does on stage while performing. Her horses are her partners in the performance, not “props.”

“When a horse performs, it becomes an artist,” Sylvia says. “We have to maintain them mentally in order for them to perform 100 percent on stage every night. If you use the philosophy of work-work-work, you’re forcing them.”

Sylvia prefers Arabians for her liberty demonstrations. She has 10 purebred Arabs and three horses that are half-Arabian and half-Andalusian, a breed from Spain. Her performance horses range in age from 2 to 20.

“People say Arabs are fiery and difficult, but I love them,” she says. “They’re more playful than other breeds and seem to enjoy their work so much. Even though I use stallions, they don’t want to fight or attack each other.”

She positions the larger, heavier half-Andalusians on the outside of the group when the horses are working at liberty. At certain times, there will be as many as 10 horses abreast, so the outside horse needs to be sturdy because the other horses may lean against him.

Sylvia remembers clearly her first Arabian horse.

“I was about 12. That horse had so much energy, but his eyes were so innocent.”

It’s safe to say, Sylvia grew up paying closer attention to animals than most young children.

“My grandfather, Charles Zerbini, always said every animal has its own silent language and it’s up to us to learn it. I feel certain people have a gift, a ‘special something’ to connect with animals. I have that with horses; my sister is like that with elephants,” Sylvia says, referring to her sister Patricia Zerbini, who owns and operates Two Tails Ranch in Williston.

Sylvia says that, although her father trained horses, she probably learned more from her horses themselves than from any one person.

“I have to say my horses taught me my work. I started putting horses together and watching them. That’s how I started learning body language and how they communicate,” she says. “I’ve learned that silent language. It’s self-explanatory if you just pay attention. Sometimes people use too many words. Words can distract. Animals have a very strong energy, and they feed off energy. They can sense when you’re sad or happy. If people would use that more to communicate—and not just with horses but with any animal—they would be amazed how much more they could get out of their animals.”

When touring with Cavalia, and other shows prior to that, Sylvia was accustomed to living on the road.

Although she and Richie have owned their Williston-area farm for nearly 10 years, she’s been away more than she’s been home over the past decade. It was common to stay on the road for eight to 10 weeks at a time, then fly home for just a few days.

“I just love coming back to Ocala, says Sylvia. “I travel to so many cities, and it’s always good to come back to the weather here and the people. I like the Southern manner here; you can lose that in big cities.”

The traveling lifestyle is as familiar as breathing to Sylvia, as it is to her English-born husband Richie, who met Sylvia in the 1990s after his tumbling troupe joined her father’s circus. Ambra, Sylvia’s 19-year-old daughter, was raised in much the same way as her mother.

“Circus families are very tight and family oriented,” says Sylvia. “We always had really strict rules when I was a child, and I raised Ambra the same way. She was on the road with me and has been everywhere in the world, but we always kept a routine. She had a tutor on the road and did her homework. She’s very grown up and level-headed for just 19.”

Ambra is also an aerialist and talented horsewoman, following in her mother’s footsteps. She performed as an acrobat with Cavalia, and when Sylvia was recuperating from a torn meniscus, Ambra performed a six-horse liberty act for the show.

Now that Sylvia is doing her own clinics, she’ll have greater control in sharing the amazing world of liberty work. One of her goals is to establish a new discipline, where people can compete in presenting their horses at liberty, just as riders compete in other types of equestrian events.

“Horses are my love and my passion; they’re so sensitive and willing,” Sylvia says. “I hope that what I’m doing will help horses and make people more aware.”

Want To Know More?

For more information about clinics and lessons, contact Grande Liberté Farm at (941) 256-1063.