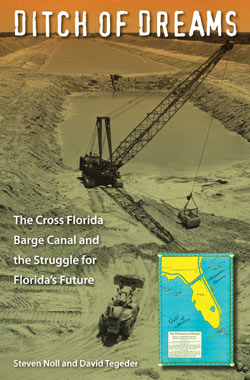

This exclusive excerpt from Ditch of Dreams: The Cross Florida Barge Canal and the Struggle for Florida’s Future reveals how Marion County played a central role in the debate.

Historians often talk about the importance of getting immersed in their work. Usually, this expression is figurative in nature, but late one Sunday morning, we took the advice quite literally. On a canoe trip on the St. Johns and Ocklawaha Rivers, we flipped our craft not once, but twice into the placid blue-green waters of the twisting Ocklawaha.

A scenic view of the pristine Ocklawaha River. Photo courtesy of State of Florida Photographic Archives,Tallahassee.

The journey, even with the unexpected swim, convinced us that our research of the Cross Florida Barge Canal was not just another investigation of the past. Indeed, the canal and its history are central to understanding modern-day Florida. Why is the history of something that never happened so important? All that remains today are the faded dreams of supporters and the physical remains of two failed efforts to cross the peninsula. And yet, the abortive canal touched far more than the river we were canoeing, a quiet stream that would have been obliterated in the wake of a giant ditch filled with relentless barge traffic.

‘A Sudden Burst Of Prosperity To Ocala’

The official groundbreaking was held on September 19, 1935, at a location on the canal route nine miles south of Ocala. Touted as the greatest moment in not just Ocala’s, but the state’s history, the ceremony was filled with pageantry and color. As if to underscore the importance of the event, President Franklin Roosevelt himself, linked by telegraph from Hyde Park, set off 50 pounds of dynamite to inaugurate the project. With stores and schools in the region officially closed by noon, more than 15,000 enthusiastic supporters gathered to hear prominent Floridians extol the virtues of the project.

At precisely 1:00pm, a deafening blast “blew Florida sand and an under stratum of shell fifty feet into the air.” The disruption immediately halted the ceremony as thousands began to scream and blow their car horns, rushing to the site of the new ten-foot crater. In spite of the blunder, boosters were confident that they were on their way to building “one of the wonders of the world.”

Following the September groundbreaking, work began in earnest in both clearing the land and digging the canal itself. Among thousands of workers, crews of 80 to 120 men removed timber and underbrush by hand for eventual excavation. While project managers established portable camps from Palatka to Dunnellon, much of the work concentrated on the Central Florida Ridge, the nearly five thousand acres of land between the Ocklawaha and the Withlacoochee.

Ocklawaha timber men transporting cypress logs by raft to Palatka in the late nineteenth century. Photo courtesy of State of Florida Photographic Archives, Tallahassee.

The 195-mile passageway would require the excavation of somewhere between 600,000,000 and 900,000,000 cubic yards of rock and dirt, significantly more than was removed to construct the mighty Panama Canal. Far from merely cutting a 90-mile path directly through the Central Florida Ridge, the project also included significant alterations to the St. Johns, Ocklawaha, and Withlacoochee Rivers.

While initial designs recognized the need to preserve “the beauty of Silver Springs” as well the Ocklawaha and Withlacoochee rivers, project engineers quickly called for “much straighter cuts.” Construction would similarly involve dredging a massive channel—500 feet wide at the shore line and 1,000 feet wide at its mouth—nearly 20 miles into the Gulf of Mexico to make a navigable entrance for the cross-peninsula passage.

With a transit time of roughly 25 hours, planners saw a new ship passing through the canal every hour of the day. Even in its narrowest sections, the canal’s width would enable two cargo ships to pass with relative ease. When compared to the carrying capacity of its predecessors, the proposed ship canal allowed for twice the traffic and nearly twice the tonnage as the Suez and Panama canals. This was to be no mere ditch, but the crowning achievement of an integrated American waterways system.

As a source of work relief, the Ship Canal counted on manual labor for excavation. Photo courtesy of Ocala/Marion County Chamber of Commerce, Ocala.

Canal construction brought a sudden burst of prosperity to Ocala. Mayor B. C. Webb jokingly complained that the town was growing so fast that municipal officials now had to install large numbers of new traffic lights. New restaurants, hotels, and theaters quickly opened as business increased between 25 and 50 percent. Native Ocalans recognized the economic importance of the project and conveniently looked the other way as bars and slot machines proliferated in their community. In one county meeting, ten applications for liquor licenses appeared on the agenda.

Camp Roosevelt, of course, provided the spark, and to some observers even posed a threat in overtaking the nearby city. The editors of the St. Petersburg Times ruefully noted that the work camp could become a “permanent city” and maybe “the future inland metropolis of Florida.”

‘Santos Was Wiped Out’

The single exception to all of this prosperity lay in the fate of Santos, a small, unincorporated, predominantly African-American community located squarely in the projected path of the waterway. It would be naive to presume that it was mere coincidence that this community would be the only one to disappear in the wake of the canal.

Located seven miles south of Ocala, Santos emerged in the late 19th century as a free black settlement along the tracks of the Seaboard Coastline Railroad. Since that time, it remained a stark reminder of the strict color line of the Jim Crow South, as well as a vivid example of the sense of community established by disenfranchised blacks.

Cut off from the hustle and bustle of Ocala, it became relatively self-sufficient with a local school and numerous black-owned businesses. As little more than a whistle-stop between larger destinations, Santos remained a small but vibrant community of hard-working and close-knit African-Americans. Reflecting the tension between Saturday night and Sunday morning, the town simultaneously supported three juke joints and three churches that were at the center of black life. As with many black towns at that time, the community baseball diamond offered additional recreational opportunities as Santos became an integral stop on the local semi-professional Negro League circuit. In addition to the usual agricultural activities, residents could work in a local rock crushing mill and a factory that processed Spanish moss for stuffing pillows and mattresses. All of these activities came to an end with canal construction.

During the Great Depression, the Works Progress Administration (WPA) employed huge earthmoving equipment to dig the Ship Canal cut.

Photo courtesy of Ocala/Marion County Chamber of Commerce, Ocala.

With the creation of the Ship Canal Authority in 1933, Santos quickly became little more than a memory. State officials flooded the area, going house-to-house along the right-of-way, purchasing land for pennies on the dollar. In December 1935, for example, the state acquired the sanctuary and lands of the Calvary Baptist Church for a mere $750.

The entire community was wiped out, with only a small Methodist church remaining. To add insult to injury, few of the town’s displaced agricultural laborers found jobs associated with the canal. Even worse, many property owners, originally proud to participate in an endeavor that would ostensibly aid their country, became frustrated that they had lost their land and community for what would become an empty promise. Unlike Rosewood, no dramatic episode of racial hostility occurred in Santos’ destruction.

The town just disappeared.

‘The Carnival Atmosphere Of Camp Roosevelt’

The rest of Marion County experienced rapid population growth. The Ocala area soon filled with more than 9,000 new residents, including “itinerant peddlers, preachers, medicine men, sooth-sayers, beggars, acrobats, and musicians” who crowded into “large and small side shows and tent meetings” in efforts to cash in on the project. Anticipating many “social problems” caused by “drifters and transients,” Marion County Chamber of Commerce Secretary Horace Smith asserted, “we are organized to cope with them when they arise.”

In spite of the carnival atmosphere of Ocala and Camp Roosevelt, few major disturbances occurred. Vagrancy became a considerable problem as transients, arriving with little or no money, put pressure on local relief rolls. Anticipating only 75 cases per month, the Salvation Army reported it actually provided lodging for an average of 416 cases per month. Fighting, public drunkenness, and petty larceny became commonplace enough that the Marion County Sheriff’s office tripled its workload after canal work started.

While local officials and camp administrators overlooked minor legal transgressions, they could not ignore signs of what they considered a far greater source of disorder: union organization. Officials felt workers were well compensated and labor advocates were little more than troublesome intruders.

In March 1936, George Timmerman, a 30-year-old St. Augustine labor organizer, was found nailed to a cross near Camp Roosevelt. Instead of investigating the incident, local law enforcement officials blamed Timmerman himself, claiming that he had staged the crucifixion to gain publicity for an ostensible sideshow career. Ocala Police Chief J. H. Spencer also tied Timmerman to left-wing causes, accusing him of “allowing himself to be nailed to the cross for communistic reasons.” After taking him to the hospital for medical attention, officers forced Timmerman to immediately leave the area. He then disappeared from Ocala and the historical record. Workers were now warned—labor organization would not be tolerated along the canal.

‘A Grass-Roots Environmental Movement’

Criticism of the canal actually began long before its groundbreaking. A group of railway executives in a February 1933 Army engineers’ hearing leveled charges that a proposed canal would destroy Florida’s aquifer. Canal excavation, they asserted, “may have a very decided effect on the underground flow in the Ocala limestone and on the wells and water supply” in Central Florida. These criticisms, however, could easily be dismissed by canal supporters as the mere grumblings of discontented commercial rivals, embittered by government support for the canal.

Four months later, however, Roosevelt received a personal letter from James Howe, his cousin residing in Daytona Beach, with no apparent ties to competing railroad interests. Calling for “a thorough investigation” of construction plans, Howe viewed the canal as a project that would bring “serious and irreparable injury” to the state.

Laying out the framework of opposition that would hold for almost 40 years, Howe listed his objections in a brief attached to his letter to the president. First, he reiterated the concerns of railroad men by proclaiming the canal’s threat to Florida’s water supply. The salt water intrusion caused by the canal would make “living in the area a virtual impossibility.”

Calling the canal “a great ditch,” he then attacked it for destroying the state’s scenery. For Howe, this was not simply a matter of aesthetics because Florida “depends for its prosperity, to a large extent, upon its tourist business.” He couched his final arguments in economic terms, calling the project “an unfair and impossible burden” and not even a beneficial work project since “the greater part of the construction would be performed by giant dredges.”

By late 1935, the opposition became so strident that many citizens increasingly feared that the ship canal’s completion would reduce southern Florida “to the status of an island.” In November, tempers were so hot that a committee met in Orlando to consider dividing Florida into two states, one north and one south of the projected canal.

Sensing growing resistance from across the state, as well as in the halls of Congress, Roosevelt cautiously backed away from the project by the end of 1935. Opposition on the national level centered on the canal as a stunning example of pork-barrel politics. Canal critics viewed the project as “utterly without economic justification.”

After the 1936 congressional defeats, the abandoned cuts southwest of Ocala were all that remained of the Florida Ship Canal. Photo courtesy of Ocala/Marion County Chamber of Commerce, Ocala.

‘The Bulldozers Stood Silent For Good’

In 1942, as German U-Boats ravaged merchant shipping off the Florida coast, Congress passed a bill authorizing the construction of another canal across the state following the same route as the abortive New Deal work project. This one, however, would be a barge canal, only 12 feet deep with attendant locks and dams. The canal would be an important link in the protected shipping of oil and gas from the fields of Texas to Eastern U.S. markets. Though it appeared canal boosters had won a great victory, Congress never appropriated the money to build the project, as more pressing war needs took higher priority. Once again, the canal was on hold—briefly.

But 20 years later, with the money encumbered, President Lyndon Johnson traveled to Palatka to initiate the groundbreaking of the Cross Florida Barge Canal. The dream of canal supporters seemed well on its way to reality until it ran up against a new generation of environmental activists determined to preserve the Ocklawaha River. Led by Marjorie Carr, these critics forged a movement centered around scientific expertise, citizen activism, and the use of the legal system that challenged a political and institutional juggernaut intent on completing the canal. Through sheer persistence—as Carr later put it, “timing, knowledge of the facts and staying in the fight until it is well and truly won”—they overcame enormous obstacles and in seven years convinced both the courts and President Richard Nixon to halt construction. Once again, the cranes and bulldozers stood silent—this time for good.

For decades, the Santos bridge stanchions remained as mute reminders of the failed Ship Canal project. Today they are barely visible through the trees near the Sheriff substation in Belleview on US 441. Photo courtesy of Florida Defenders of the Environment (FDE), Gainesville.

‘The Canal Was Only Half The Battle’

Though construction halted in January 1971, controversy over the canal and its legacy did not stop. The Rodman Dam, which the state of Florida officially designated as the George Kirkpatrick Dam in 1998, and its adjoining reservoir had already been completed and still remain in place today. For environmentalists, stopping the canal was only half the battle, as their efforts centered on preserving the Ocklawaha River. To this day, they cannot claim complete victory until the dam is removed and the Ocklawaha is restored to its original free-flowing condition. This will provide, according to a pro-restoration press release, “a rare opportunity to correct an environmental disaster.”

On the other hand, their opponents no longer seek the completion of the canal. Instead, their goal is to retain the dam and the Rodman Reservoir created by it. In their eyes, the dam established a “viable and complex ecosystem that supports a wide variety of native plants and wildlife.” The once inaccessible river has now been replaced by an expansive reservoir providing significant recreational opportunities for the general public. Removal of the dam would drain the reservoir and thus eliminate one of the premier bass fishing spots in America. Since 1971, neither group has had the political clout to impose its will on the other and bring an end to the controversy.

In December 1992, politicians in Tallahassee met to review a recommendation on turning the former canal into a linear park. Though the public meeting dealt with many of the broader concerns related to the transitional process, contentious debate centered on the fate of Rodman. Once again, adversaries descended on the capital and staked out their positions and hopefully sway government officials their way.

But for Marjorie Carr, the activist from Micanopy who had fought the canal project for decades, it was a bittersweet moment because her illnesses made her too weak to appear in person. Instead, her supporters brought along an emotional videotaped appeal from their leader. In it, Carr called the Ocklawaha “a natural work of art” and asked the Florida Cabinet to “restore it and care for it as if it was a Pieta by Michelangelo.” She summarily dismissed the economic and recreational concerns of those who pleaded for retaining Rodman Reservoir. “I realize bass fisherman will be inconvenienced,” she said. “I trust they will find good fishing in nearby lakes.”

Marjorie Harris Carr, “Our Lady of the River,” at the Ocklawaha River, 1966. Photo courtesy of Florida Defenders of the Environment (FDE), Gainesville.

But Rodman Dam—“that obscenity, that ridiculous mistake, that hideous monstrosity,” according to Carr—remained. By the summer of 1997, “feeling lousy,” tethered to an oxygen bottle, and forced to move from her cherished Micanopy homestead to a patio home in the middle of Gainesville, Carr plaintively asked, “Will I live to see it [the Ocklawaha] run free or not?”

She railed against those who failed to see the wisdom of Rodman’s removal. She complained that bass fishermen “ought to be ashamed of themselves” for their unyielding support for the reservoir. At the same time, Carr reaffirmed her sentimental attachment to the river.

“Once the dam is gone,” she reflected, “the manatees will be able to come up there during the winter. What a sight that will be.”

In late May of 1998, the legislature commemorated Carr by naming the Cross Florida Greenway after her. In many respects it marked the crowning achievement for a woman who had dedicated her life to environmental protection.

Despite the ongoing controversy over the fate of Rodman Dam and the Ocklawaha River, the establishment of the Marjorie Harris Carr Cross Florida Greenway turned the centuries-old boondoggle of a canal into a model conservation project. Florida’s legislature took advantage of an unprecedented opportunity and established a 107-mile greenway dedicated to recreation and natural preservation in a region undergoing rampant growth and economic development.

But the final chapter’s not written just yet.

As Floridians struggle with concerns about growth and preservation in a fragile and increasingly finite environment, the history of the canal looms as a cautionary tale over present-day public policy.Whether the issue is the expansion of port facilities to accommodate giant Asian cargo ships or the construction of a modern high-speed rail system, questions about the cost and necessity of public works projects will become all the more pointed in an era of scarce financial and ecological resources.

Perhaps most controversial is the problem of Florida’s diminishing water supply. Current public policy debates center on solutions ranging from simple conservation measures to enormously expensive water projects like desalination plants and restoring the natural flow of the Everglades. One such proposal involves diverting flow from the Ocklawaha and St. Johns Rivers to meet the demands of central and south Florida. Seen against the historical backdrop of the Cross Florida Barge Canal, Florida’s current water war is but the latest skirmish in a never-ending struggle between different interests and visions.

Stay tuned.

Want To Know More?

Want To Know More?

Go to upf.com to purchase Ditch of Dreams: The Cross Florida Barge Canal and the Struggle for Florida’s Future or hundreds of other titles of local interest.