With their grand presence, the eagle and the hawk are impressive examples of powerful birds of prey. But vultures? Aren’t they just nature’s clean-up crew? A black vulture at Silver Springs named Lurch might alter the perception of these oft-maligned scavengers. You may never look at vultures the same way again.

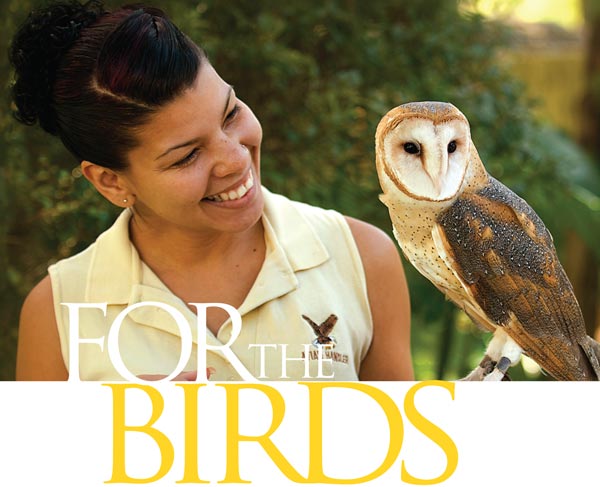

“Vultures are extremely intelligent and more personable than most of the other birds because they live in a flock,” says Andrea Junkunc, a senior trainer with the attraction’s Wings of the Springs bird show, which soars twice daily at Ocala’s longtime nature park.

-DSC_6113[1].jpg)

“Thor,” a Spectacled Owl

Of course, I didn’t know that vultures were so social and easily trained until I watched Lurch show off for the crowd as she interacted with her trainer. Elegant and graceful, she (yes, Lurch is female) clearly enjoyed performing. She actually seemed a bit of a ham and in no hurry to cut her visit short.

Leave it to the trainers to come up with a show that manages to combine hawks, vultures, chickens, and ducks in one performance. Not to worry—predators and prey are never onstage at the same time. The 25-minute show flew by (no pun intended) and left me wanting to know more about the surprising variety of feathered participants.

A number of the birds in the shows are either rescue or rehab cases. Some can never be released back into the wild because of the extent of their injuries, but they can still enjoy a quality life. “Dancer” is an impressive red-tailed hawk that was hit by a car and brought to the park for rehabilitation. A lingering equilibrium problem keeps her from flying during the show, but she gives guests a close look at one of Florida’s native hawk species.

-DSC_6404[1].jpg)

“Sundance,” a Double Yellow-Headed Amazon Parrot

Other performers were born in captivity and have been part of the show since its inception 11 years ago. “Sundance,” a double yellow-headed Amazon parrot, falls into this category. Boasting an amazing vocabulary of 200 words, Sundance is now in her twenties, and has a life expectancy of 60 to 80 years. Don’t be shy about speaking up if it’s your birthday—Sundance regularly sings “Happy Birthday” to guests at the show.

Training and conditioning a bird for this type of performance requires an enormous amount of time. Approximately 270 hours are invested before just one of the majestic birds is ready for a crowd. Although some birds remain on the handler’s gloved hand during their appearance, others fly freely, zipping close above the heads of the spectators with a thrilling rush of wings.

The trainers instruct guests to put away any food before the show starts—for good reason. Some birds have been known to make a detour during their performance to grab a snack from an unsuspecting patron.

Shows take place in a tree-shaded, open-air pavilion, so the untethered birds could simply fly off if they had a mind to leave. The trusting bonds they’ve developed with their handlers, however, keep them close by—a bite of beef heart or a tender morsel of mouse helps, too!

While you can’t eat or smoke during the show, you are welcome to take photos, and the venue offers an opportunity to capture some incredible shots. Where else in Ocala are you going to come face-to-beak with an American kestrel, a barn owl, or a Harris’ hawk in full flight?

The shows aren’t limited to birds from Florida, or even North America, which allows from some rare-breed surprises. There’s “Tequila,” a Mexican crested caracara, the national bird of Mexico and one whose image appears on certain Mexican coins. This long-legged member of the falcon family dines on carrion and snakes.

“Thor” is a spectacled owl who, thanks to his dramatic feathering pattern, truly looks as if he’s wearing dark-rimmed glasses. Don’t believe the myth about owls turning their heads all the way around, though. In truth, they can only turn their heads about 270 degrees.

Perhaps the most unusual bird in the show is “Cirrus,” a Bateleur eagle — a large, strikingly marked raptor native to Africa.

“They’re very rare. Only about 300 are left in the wild because of habitat destruction and poaching,” says Junkunc, who has been with the bird show for seven years. “More are now found in captivity than in the wild.”

Although the trainers take to the stage every day, they also spend many hours behind the scenes handling the decidedly less glamorous tasks. Someone has to dice up all the beef hearts, chicken necks, mice, rats, and insects.

Far left: “Kahlua,” an American Kestrel; Left: “Tequila,” a Mexican Crested Caracara; Below: Andrea Junkunc with “Cirrus,” a Bateluer Eagle

“We do all the food prep,” offers trainer Jamie Ballard.

Along with specialized diets, all birds are weighed daily and their condition carefully monitored.

“One of the first signs a bird is sick is a sudden decrease in weight,” explains Junkunc.

She adds that birds in captivity live twice as long as birds in the wild thanks to diet, vitamins, veterinary care, and a safe environment. The shows offer a chance for the public to learn about the different species of birds and at the same time, provides a source of enrichment for the birds who clearly seem to enjoy the spotlight.

“The most rewarding thing is to be able to present these birds to people who wouldn’t be able to see them any other way,” says Junkunc. “We hope they appreciate how beautiful they are and do what they can to protect them.”

“It’s also rewarding to be able to release an animal back into the wild when possible,” Ballardn adds. “That’s always the goal.”

Silver Springs launched its Wildlife Rehabilitation Program in 1973 and since then has rescued and rehabilitated thousands of birds and animals.

-DSC_5920[1].jpg)

Jamie Ballard with “Dancer,” a Red-Tailed Hawk

“We can receive up to around 500 animals in a year through the rehab program,” notes Joanne Zeliff, wildlife manager for Silver Springs. “Many of the birds seen in the show or at the Outpost have been permitted and added to the collection through the rehab program as permanent educational birds. Many of the injuries were wing injuries suffered when they were hit by cars.”

Hawks, opossums, and gopher tortoises, as well as baby songbirds that haven fallen from nests, are examples of rescues brought to the facility. If you do find a baby bird on the ground, you should always try to return it to the nest first, Zeliff says. It’s a myth that a mother bird won’t take back a baby if it’s been touched by human hands.

“The hard work by the staff, especially when they take them home overnight, allows many of the orphaned babies to get a second chance,” she adds. “The ultimate goal for any rehabber is to release these animals back into the wild.”

Not to give anything away, but there is at least one performer in the Wings of the Springs show without feathers. “Sakari,” a wild Florida hog, was a two-day-old orphan when she was brought to Silver Springs several years ago.

And just what exactly is a four-legged critter doing in a bird show?

“You’ve heard the saying ‘When pigs fly’?” Junkunc asks with a laugh. “We’re working on that!”

Want To Know More?

silversprings.com

(352) 236-2121