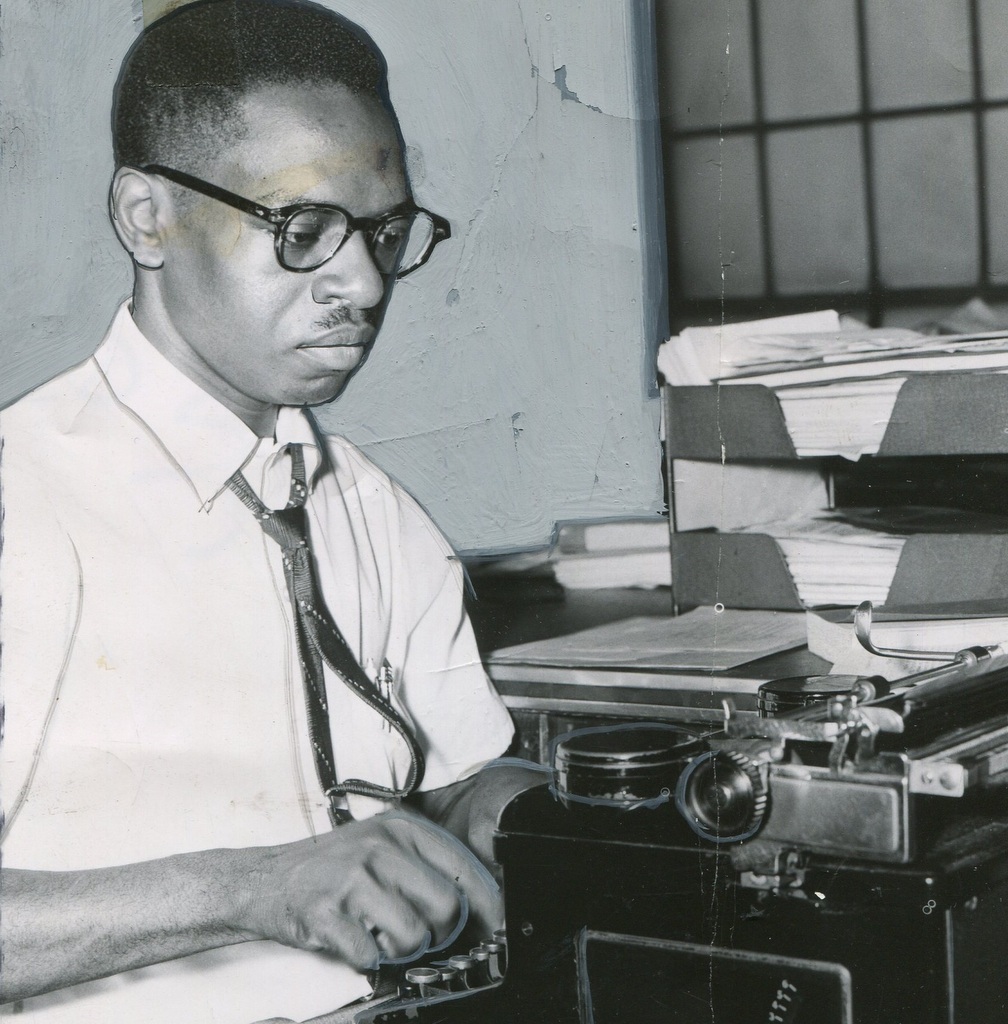

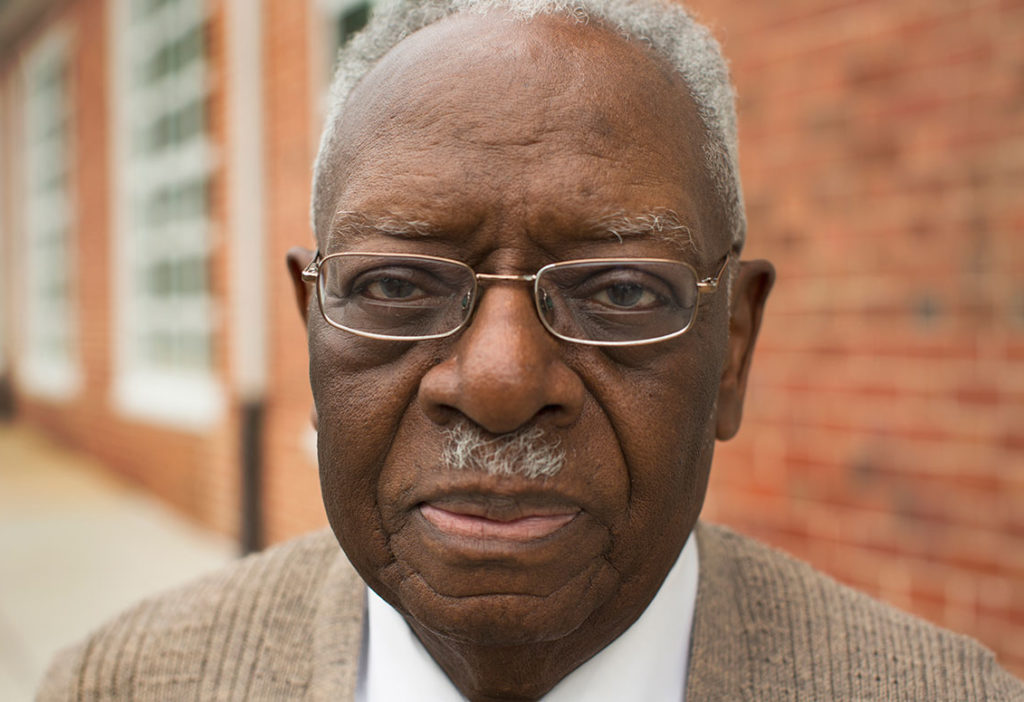

Moses J. Newson—author, reporter, editor and public affairs specialist—is an American treasure. In Ocala, he is affectionately called “Uncle Mose” by his nephew Wendell Johnson.

As a newspaper reporter and later editor, Central Florida native Moses Newson sometimes risked his life to bear personal witness to virtually every tear-stained milestone of America’s civil rights movement.Newson’s career highlights read like a History Channel biopic. As a writer for the Tri-State Defender in Memphis, Tennessee and later as a reporter for the Baltimore Afro-American, he covered desegregation in Hoxie, Arkansas; Clinton, Tennessee; at Central High in Little Rock; and at the University of Mississippi. He also reported on the infamous Emmett Till murder case in Missis-sippi, interviewed the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., traveled with Medgar Evers and was part of the May 1961 Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) Freedom Ride.

“Probably no single reporter with the exception of Simeon Booker covered more of the early events of the civil rights movement than Moses Newson,” notes Eugene Roberts, former managing editor of The New York Times.

Responding to this reporter’s questions via email correspondence through one of his daugh-ters, Newson, 95, recalled a particularly harrowing experience from those turbulent times.

“The Freedom Riders story was probably the most challenging because of a lack of being able to communicate with others,” he shares. “There were no cellphones then. When I called my wife from Atlanta on Mother’s Day (May 14, 1961), I told her I would be on one of the Freedom Ride buses headed to Birmingham, Alabama. But in Anniston, a mob of angry Ku Klux Klan supporters attacked the bus I was on and threw a firebomb behind the seat where I was sitting. I put my camera under my seat and helped as many people as I could. My camera was left on the bus, charred beyond further use. We got it back from Greyhound, and it was destined for museums. It was late Mother’s Day before my worried wife learned through another source that I was OK.”

When asked why he put himself at risk, he replies, “I was a journalist and we always took the position that Black journalists needed to be on the scene where news was being made.”

That philosophy inspired him to report on global civil rights events, such as the Independence Ceremony in the Bahamas, a Commonwealth Nations meeting in Jamaica, post-civil war struggles in Nigeria and protests in Panama, South Africa and Cuba.

But prior to Newson blazing a trail for Black journalists, he worked alongside his father in Fruitland Park, 30 miles south of Ocala in Lake County, where he was born. He then served in the U.S. Navy before learning his craft at Lincoln University in Jefferson City, Missouri.

“The reason I got my journalism degree in Missouri was because, at that time, there were no schools in Florida that would accept Black students into the journalism degree program,” he says.

A winner of numerous writing awards from the National Newspaper Publishers Association and the Maryland-Delaware-DC Press Association, Newson served thrice on Pulitzer Prize jury panels and covered four presidential nomination conventions. In 2014, he was inducted into the National Association of Black Journalists Hall of Fame.

A Native Son

Wendell Johnson, 60, of Ocala missed those early reels of Newson’s life. His fondest recollections begin in the 1970s, when his uncle (who he called Uncle Mose) and his Aunt Lucille Wallace Newson, on his mother’s side, left Baltimore for balmy summer vacations in Florida.

Photo by Bruce Ackerman

Johnson grew up in a neighborhood with several family members nearby. His childhood home on Southwest Second Street was down a dirt road from his grandmother’s home—“The Big House”—on what is now Martin Luther King Jr. Avenue. And his Aunt Dot lived a street over from his home, on West Fort King Street, all within walking distance.

Johnson remembers those visits as the “best times” of his pre-teen life.

Reenacting the excitement, Johnson says, “I used to be looking down the road” in anticipation of the Newson family’s annual summer vacation to Ocala. “We did not go to sleep for two weeks.”

Newson, “the best uncle in the world,” according to Johnson, has similar memories of a tradition that continued until their last visit in 2016.

“Ocala, Florida is where my wife’s family relocated when they moved from the Leesburg/Fruitland Park area,” recalls Newson. “Our summers were for spending quality time with our families and friends. We would visit for two weeks, often staying in Ocala with Lucille’s large family. Anything you needed, Ocala had it.”

Lucille and Newson met while attending high school together in Leesburg. They married in 1948 and had four daughters. After 73 years of marriage, Lucille passed away in 2021. One of the daughters, Pat Newson Benns, is the same age as Johnson. Johnson’s mother, Rosa Wallace, raised three sons and two daughters in Ocala. Because Johnson’s mother did not drive, their vacations were limited. But when the Newsons came to town, joined by other family members from as far as Chicago, the gatherings turned into a celebration, complete with trips, two or three times a week, to places such as Disney World and Busch Gardens. Johnson felt blessed because most of his friends could not afford those luxuries.

“Cousins would walk back and forth,” Johnson describes the days they spent hanging out between family residences. “Back then, the roads were dusty limerock roads that tractors had to smooth out.”

Johnson says his cousin Pat feared the dirt, so he would put her on his back and carry her to The Big House.

Benns echoes similar experiences: “Two weeks in Florida with our aunts, uncles and cousins were the best two weeks of the summer. There were family picnics, fish fry events and many late-night bid whist card games. We spent time at Silver Springs with the glass-bottom boats, the (Ocala) Jai Alai, Daytona Beach, Disney World and Universal Studios.”

Competitions around card games still dominate family gatherings.

Johnson recalls that youngsters did not participate in the adult conversations at the card table in those days and says Newson called the children “jitterbugs.” He says he and Pat would sit and watch, longing for the day they could play cards with the grown-ups and join in the banter.

Listening to Elders

“Tap into the wisdom of older folks while they are alive,” advises Johnson, who has made the art of listening to his elders a lifelong practice. He believes he is strengthened by attaching himself to wiser people, like Newson.

He jokes, “You know what people your age know.”

Newson’s travels intrigued Johnson early on. Two incidents specifically. The first was an occasion when Newson traveled to cover a Miami Dolphins practice.

“He was the only Black reporter that day and he said they would not let him in,” Johnson explains, until a white reporter vouched for him. Johnson boasts that Newson wrote about the occurrence and was never again denied access.

The second event involved a Confederate flag waving at an establishment Newson visited in South Carolina. Johnson says Newson was off ended by the flag and when he returned home he wrote a letter and the flag was later removed from that location.

Johnson says his uncle has always been calm, gentle and wise. He never saw the civil rights journalist get upset, even as Newson replayed infuriating moments from his past. Johnson said Newson encouraged the children to enjoy their youthfulness.

“Almost like he wanted to protect us,” Johnson says.

Johnson also credits his father, Solomon Shuler, who died in 1997, for instilling a strong work ethic within him. Shuler, a field contractor, harvested watermelon, oranges and peanuts and enlisted his young son to work with his 150-person crew. After work, Johnson says, his dad would take him to the store for a soft drink and an “ikey mike”—a gingerbread cookie with icing. In the back seat of Shuler’s truck, he would eat his snacks while listening to his father, his Uncle Jack and other men talk under a shade tree.

Later in life, Johnson would gather knowledge from men 30 and 40 years his senior. Locals like the taxi driver James Roberts, businessman Austin Long, historian Albert Jacobs, William James, Whitfield Jenkins, Ed Fordham and others.

Johnson eventually experienced adult conversations with Newson.

“He loves sports,” says Johnson.

Newson coauthored Fighting for Fairness: The Life Story of Hall of Fame Sportswriter Sam Lacy with his friend and autobiographer, Lacy.

Johnson professes that Newson’s wealth of knowledge overwhelms him. He refers to his uncle as the “country boy who did all of this,” including lectures, interviews and phone calls from Hollywood and New York filmmakers.

“Someone was always contacting him about a movie or Black history or the voting issues,” says Johnson.

Justifiably impressed, Johnson invited three buddies to meet Newson while attending the Million Man March in Washington, D.C., in 1995.

Family Impact

Johnson has grown from “jitterbug” to his family’s “go-to guy” and exhibits Newson’s giving characteristics. As foreign to cold weather as Benns was to dirt, Johnson chose not to move up north. Instead, he stayed in Ocala, raised four kids and took them on biannual vacations.

With lessons from his father on work and a mother who taught him how to cook anything he and his brother, Maurice, killed and brought home to eat, Johnson has worked to off set food desert issues in the West Ocala community for 25 years. On Fridays and Sundays, he provides fresh fruits and vegetables through his company, Fresh Florida Fruit, on the corner of Silver Springs Boulevard, north of Mary’s Cleaners.

“The freshest food is found on the side of the road,” declares Johnson.

From 2001 to 2007, his generosity extended to the Lake Weir High School track team.

“I fell in love with those kids,” says Johnson, who changed his work schedule to accommodate his coaching assignments.

Johnson says he “loves talking to kids” and acts as an influencer in the lives of his nieces and nephews in Virginia, New Jersey, Delaware and Florida. He says he enjoys guiding them to better decisions based on the knowledge he has received from his elders.

“It meant a whole lot to have my aunt and uncle come visit,” Johnson says. “I will never forget the impact he had on my life.”

Photo by Brian Palmer

And Johnson’s contributions have not gone unnoticed.

“One of the things I appreciate most about Wendell is that he is always helping and supporting other family members,” Newson asserts. “His support of young family members is legendary.” OS