In searching the past for facts about the prominent players in the local whiskey trade and one famous figure whose involvement was something of a mystery—until now—we uncovered a mysterious death, old debts and a surprising reversal of fortunes.

The Ocala/Marion County area has a long history when it comes to hooch. At one time, moonshine was a booming industry that supported many other local small businesses, according to local historian and genealogist Celeste Godwin Viale. One story that was passed down to her was about a “shine” distiller who received word that some folks in New Jersey wanted to place an order for some aged whiskey. Legend goes that he reached in his pocket, pulled out a tin of Prince Albert ground tobacco—a mahogany-colored variety with subtle notes of cocoa, vanilla and molasses—sprinkled a bit into a bottle of moonshine, shook it up and then shipped out his Cracker “whiskey” to some very satisfied folks up north.

A tale that involves actual whiskey, that has had some curious locals buzzing for years, is not exactly a “straight” story. In a county full of historians and enthusiasts, it is somewhat intimidating to try to unwind it. The bit of history in question revolves around William LaRue Weller.

For those of you who know your whiskey, the name probably brings to mind the award-winning Kentucky straight bourbon whiskey. This uncut and unfiltered, hand-bottled bourbon, from Buffalo Trace Distillery, is thought to be the best in the category by many aficionados.

Born in 1825, Weller was the grandson of German immigrants who moved to Central Kentucky in 1794. His grandparents settled in LaRue County in 1800. Like many farmers at the time, William’s grandfather was also a small-scale distiller who taught the young man his trade.

William’s mother, Phoebe LaRue Weller, was the daughter of John P. LaRue, an early settler in the region and the man for whom LaRue County is named.

As young adults, William and his younger brother, Charles, opened a trading company in Louisville and began selling their own bourbon brand, William Larue Weller & Brother.

William then established himself as a true distilling pioneer when, in 1849, he switched the second grain in his bourbon mash from rye to wheat and invented wheated bourbon, which possesses a considerably richer and smoother flavor.

Sadly, Charles was murdered in 1862 while trying to collect on a business debt in Franklin, Tennessee.

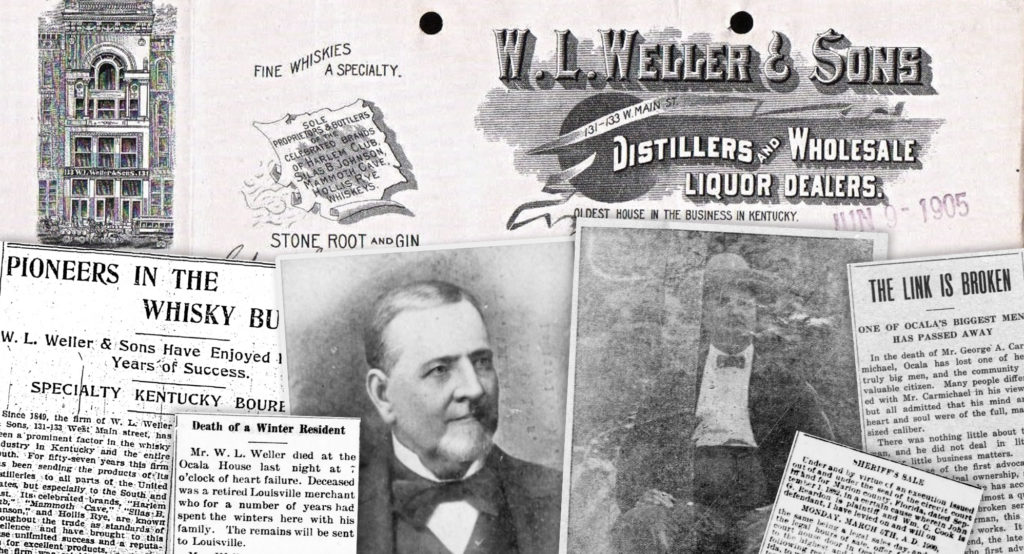

Following Charles’ death and with his sons coming of age, William changed the company’s name to W. L. Weller & Sons in 1887.

In 1893, William hired Julian “Pappy” Van Winkle as a traveling salesman. A few years later, when he retired, his brother John and eldest son George took over the business.

Eventually, William’s namesake company merged with Pappy Van Winkle’s A. Ph. Stitzel Distillery to form the Stitzel-Weller Distillery. It became renowned for such brands as W.L. Weller, Old Fitzgerald, Rebel Yell and Cabin Still.

Since 2002, the Van Winkle and Weller brands have been distilled and bottled by the Sazerac Company at the Buffalo Trace Distillery as a joint venture with the Old Rip Van Winkle Distillery company.

If you’re wondering where all this is leading—and why wouldn’t you—the fact is William LaRue Weller died right here in Ocala on March 23rd, 1899 at the age of 73. Yes, that grand old Kentucky boy spent his last days and punched his ticket in Marion County.

This has generated much speculation over the years as to how exactly he wound up here. Some believe he settled locally after he retired, while others thought he had family ties to the area.

As a matter of fact, Mr. Weller had not relocated to the area nor did he intend to. And we could find no evidence of his family line among our citizenry. But he sure did like to visit.

On March 24th, 1899, The Ocala Evening Star carried a story called “Death of a Winter Resident,” that said Weller had passed away the night before from heart failure. It revealed that for the previous 10 years he and his wife had spent several months a year in Ocala.

The Louisville Courier-Journal explained that he began his sojourns here because of his asthma which he had for many years.

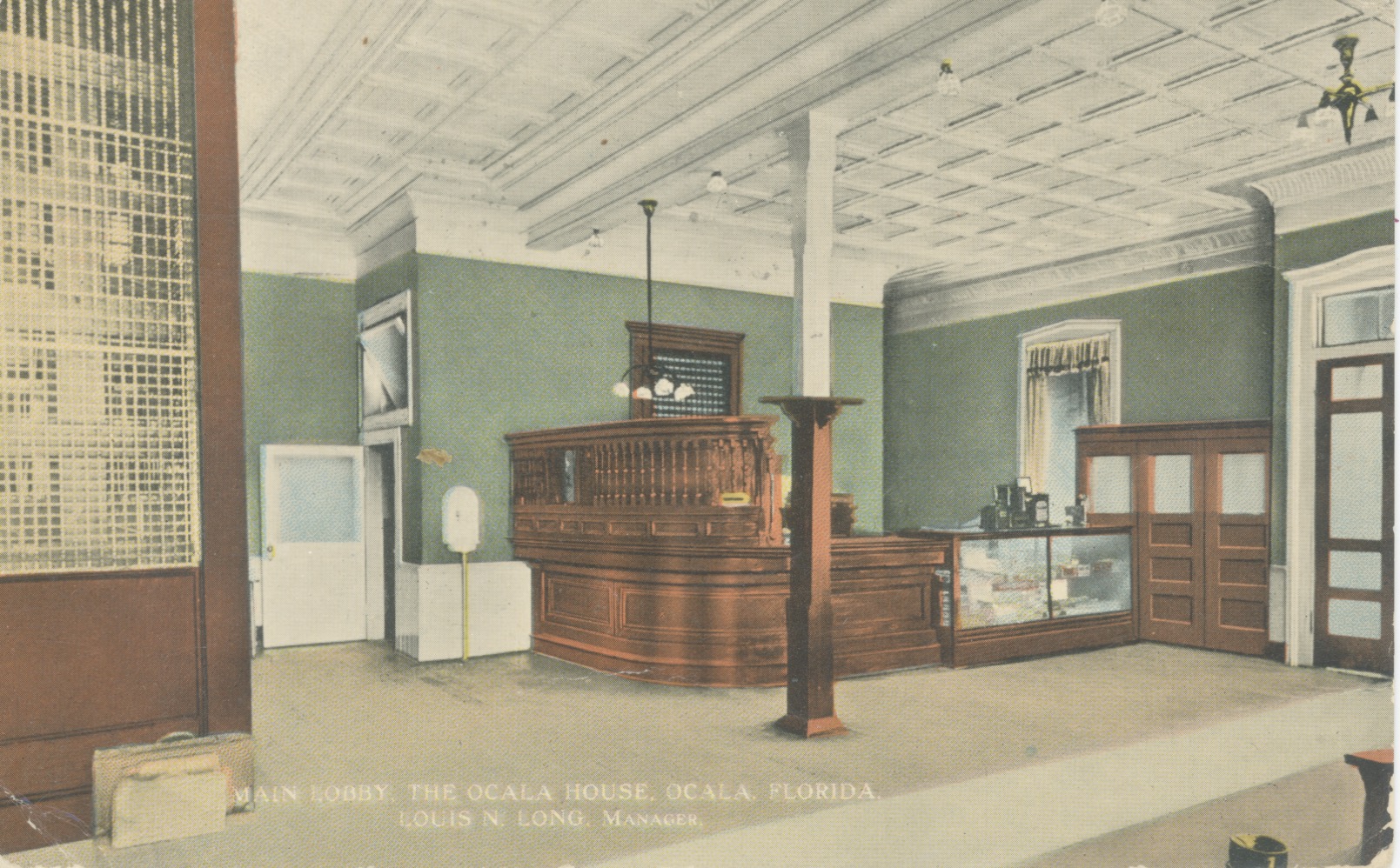

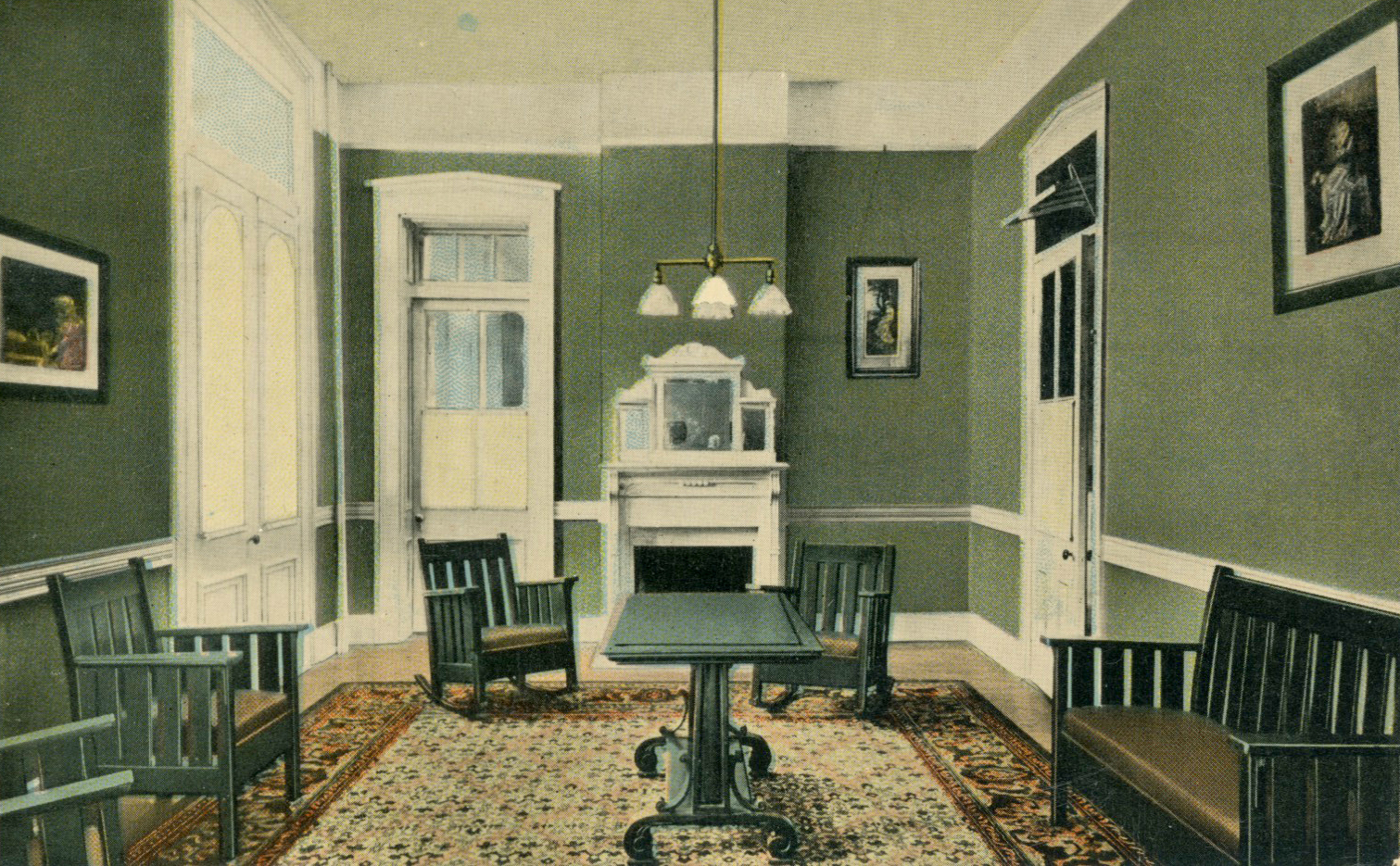

His winter home during those visits was the Ocala House hotel, considered a top resort of the day. Owned by hotelier and railroad mogul Henry Plant, it was widely marketed as one of the finest semi-tropical resorts in the world. Newspaper advertisements boasted that it was “reached by fast trains from all points of the compass.” These ads, many of which appeared in Kentucky papers, billed the Ocala House and other local hotels as “The Famous West Coast Hotels.”

In a column called “Ocala House Notes” in The Ocala Evening Star, that appeared during the same time period, a notation that is not identified as either editorial or advertising reads, “The climate of Ocala is beginning to be understood as the driest and most invigorating for all persons suffering from pulmonary troubles.”

From One Whiskey Family to Another

George Carmichael arrived in Ocala from Alabama in the early 1880s with his family and quickly established himself as an enterprising businessman. With the help of his teenage son Columbus “Ed” Carmichael, he opened a combined saloon, wholesale whiskey business and grocery store. George was also an alderman, who for more than a quarter of the century was a member of the city council.

Ed not only inherited his father’s business acumen, but also his sense of community service, serving for many years as one of the first chiefs of Ocala’s volunteer fire department

In December of 1896, The Ocala Evening Star reported that the Carmichaels erected a three-story frame building in the rear of their saloon. The building was the largest in north Ocala.

In 2012, a beloved local historian, the late David Cook, wrote about the Carmichaels and the 1890s campaign to make Marion County a dry one. “The anti-alcohol faction in Ocala was moving closer to another of those wet-dry referendums that roiled the county periodically,” Cook stated.

He explained that those pushing for prohibition were up against “more politically powerful saloon keepers and liquor manufacturers. Naturally, the king of Marion County’s distillers, George Carmichael, was the head of the wet faction,” he asserted, noting that the younger Carmichael was held in high esteem. “The fact that Ed Carmichael, George’s son and partner in the legal whiskey-making business, was among the most popular young men in Ocala showed he had earned considerable political influence.”

Cook states that in addition to the whiskey distillery on North Magnolia (possibly Ocala’s first), which was located next to the Florida Peninsular Railroad station, the Carmichaels owned a group of saloons located all around Ocala.

“Carmichael and his group were told they could continue to make and sell alcoholic beverages until a final court decision came down,” Cook detailed.

However, he offered that “the prohibitionists already had won somewhat of a victory over the saloon keepers. The dry crowd had browbeat the city council into adopting an ordinance that required the saloons to remove curtains or shades from windows and keep doorways open on Sunday mornings so the public could see who was drinking when they should have been in church.”

The battle raged until March of 1899, when the prohibitionists lost their campaign. However, the damage seems to have already been done to the Carmichaels’ decade-old business because, on March 7th of the same year, many of their holdings (including an enormous stock of various alcoholic beverages) was sold off at a public auction for $1,050 to satisfy unpaid debts, by the Marion County sheriff, in front of the county courthouse. The jewel in their crown, the saloon and distillery on the south side of Ocala’s downtown square, on Broadway between Southeast First Avenue and Magnolia Avenue, was among the 11 properties.

The man who cast the winning bid was that familiar fellow from the beginning of our story, William LaRue Weller, who was in town for his winter holiday. In an ironic turn, he died just 16 days later. And there is no evidence that he ever officially took possession of the holdings. Several of his children joined his wife in Ocala and transported his body back to Louisville.

His eldest son, George, returned to Ocala about a month later, presumably to liquidate the properties. However, based on research conducted by the Marion County Clerk of Court and Comptroller’s office, the only record of any sale of said properties by a member of the Weller family involved the one located on the square, by William’s sons George and John to D. Elmore Davidson on December 20th, 1900. Davidson had joined the Carmichael & Son Company when they had reformed the business in June of 1900 through articles of incorporation. It was described as “conducting a general mercantile business, bottling and handling of soda waters and other drinks, buying and selling real estate.”

They were later able to expand the building and operation. During the early 1900s, they were shipping alcoholic beverages all over the Southeast United States, mostly in case lots. Among its numerous products was Fort King whiskey, made in Ocala. But by 1908, local prohibitionists were on the warpath again.

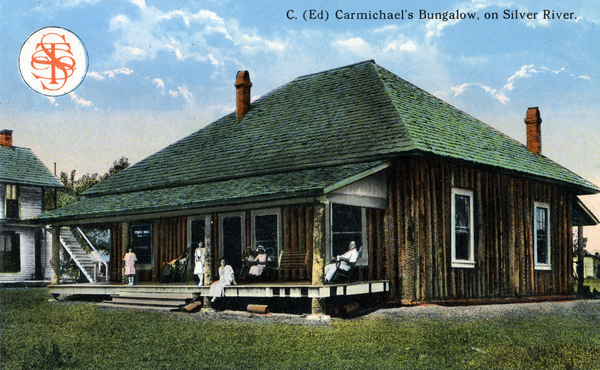

George died in 1915, the year Marion County voted to ban all alcohol sales within its boundaries. Carmichael & Son was forced to close and Ed turned his attention to developing Silver Springs into a tourist destination.

One outstanding mystery surrounds Ed’s son, who he named…wait for it…Weller LaRue Carmichael. Why he was named after the famous Kentucky whiskey man was a mystery we couldn’t crack. Perhaps it’s one of those obscure facts lost to time or perhaps someone out there knows the answer.

They say that the perfect whiskey can transport you to another place. Maybe an interesting tale about whiskey can transport you to another time—full of pioneering men and good hooch.