When does 2+2=1?

Some say it’s when you try to add up the need for Common Core Standards in our schools. Just what is Common Core and why do some feel it is needed to make your child a better student?

When does 2+2=1?

Some say it’s when you try to add up the need for Common Core Standards in our schools. Just what is Common Core and why do some feel it is needed to make your child a better student?

A Brief History of Common Core

The Common Core State Standards Initiative is designed to establish consistent educational standards in the United States. It is today’s end product of a standards and accountability movement that began with the publication of A Nation at Risk: The Imperative for Educational Reform, a report by the National Commission on Excellence in Education in 1983.

Along with the information provided in A Nation at Risk, research in the mid-1990s began to reveal that American students were scoring poorly compared to students in the world’s other industrialized nations. This research was seemingly verified when in 2000 the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) began testing students around the globe in mathematics, science and reading literacy.

In the last round of tests, performed in 2012, PISA showed that the average score of U.S. students ranked 29th in mathematics, 22nd in science and 19th in reading literacy compared to 65 of the world’s other advanced countries. The State of Florida chose to be tested both within the U.S. education system and as a separate individual education system. The results of those tests showed that Florida students ranked even lower, falling below the U.S. average in all three subjects.

American educators and politicians have long feared that if American education standards continued to lag behind, it would put the nation at a disadvantage both in the business world and as a global military power. Their solution was to take a close look at the American system of education to determine whether changes needed to be made in order to improve our students’ international standing. Every presidential administration for the last three-and-a-half decades has attempted to improve the American education system, and all have used standards-based education as a foundation.

In 2010, the Common Core Standards for math and English language arts were released, and the federal government urged states to adopt them. Contrary to popular belief, Common Core is not a product of the federal government, and the government does not mandate states to adopt the standards. Common Core was initiated by the National Governor’s Association and the Council of Chief State School Officers, and state participation is completely voluntary, although there is an incentive program provided by the federal government designed to financially entice participation.

This incentive program, named Race to the Top, gives states “points” for adopting common standards, improving low-performing schools, adopting programs that expand the creation of charter schools, maintaining state data systems aligned with federal data systems to record progress and utilizing performance-based evaluations for teachers based on their effectiveness. States are awarded federal funds based on scoring enough points. Florida was awarded $700 million in Race to the Top funds.

Since the standards’ establishment, the majority of states have adopted all or part of them, but many have altered them to best suit their individual preferences. The one common goal of federal, state and local educators, whether adopting Common Core standards or not, is to ensure that when a student leaves high school they have the education required to either attend college or effectively begin work in their chosen career field.

According to Common Core creators, the initiative is designed to set a common standard of learning that each child should reach by the end of each grade level; it does not deal directly with school curricula. School districts are free to determine their own curricula, and their teachers have the freedom to create their own methods of instruction.

Standardized Education In Florida

Florida’s first attempt at standardized education began in 1996 with implementation of the Sunshine State Standards, which were designed to provide “greater accountability for student achievement at each grade level.” These standards covered English language arts, mathematics, science, social studies, physical education, world languages, fine arts and health education for grades kindergarten through 12. Students were tested each year in grades three through 10 on varying subjects utilizing the Florida Comprehensive Assessment Test (FCAT).

In 2008, the standards were revised and renamed the Next Generation Sunshine State Standards. The standards still used FCAT testing to ensure all students were learning the required material at the required pace, and end of course (EOC) assessments were added to measure student proficiency following completion of specific courses, such as algebra I or biology I.

Florida law directly tied school funding to student performance on these tests. Higher performing schools were rewarded with higher school funding, and lower performing schools were penalized. Opponents to FCAT testing argued that the poorly performing schools should have received the increased funding in order to hire additional staff to increase performance standards, thereby creating parity in the state’s school system. Opponents also felt far too much emphasis was being placed on students passing the test and too little emphasis was being placed on actual learning.

These objections were one of the catalysts behind the creation of the Common Core Standards. Common Core creators say they are attempting to shift the emphasis back onto learning and away from standards-based testing. Although the Common Core approach will also entail year-end testing, proponents of Common Core feel that it will once again return focus on how students can learn best and how teachers can teach more effectively.

In 2010, the state adopted the Common Core State Standards, which were renamed the Florida State Standards in 2014 when 100 amendments were made to the standards. FCAT testing has been replaced with the Florida Standards Assessment tests, end of year assessment tests produced by the American Institutes for Research (AIR). The Florida Standards can be read in their entirety online at flstandards.org, and the Common Core Standards can be found at corestandards.org.

Although the name of the year-end test has changed, the Race to the Top policy of awarding higher achieving schools and teachers remains, a point that Common Core opponents says does little to change Florida’s “high-stakes-testing mentality.”

It’s All Relative

When it comes to the mechanics of Common Core, where do the experts stand?

According to William McCallum, distinguished professor (on leave) from the Department of Mathematics at the University of Arizona, who was the chairman of the team that wrote the Common Core Math Standards, Common Core is generally misunderstood and is only a guide for schools to use to set up their own approach to learning.

“The Common Core establishes expectations at the end of each grade level but does not dictate how to get there,” says McCallum. “So there is more than one approach to teaching that will achieve the standards; there is no single ‘Common Core approach.’”

Belleview resident, Michael Losito, who has taught mathematics at Belleview High School for the last 12 years, agrees—with certain reservations.

“Yes, Common Core standards do allow schools and teachers to set their own curriculum, but when you have a certain standard of learning that has to be met by the end of the school year, how much freedom do you really have? A set amount of defined material has to be learned before end-of-year testing, and that material has to be taught, so where is the freedom? Teaching styles may differ slightly, but the material that must be taught is the same for every teacher.”

Marion County Public Schools Superintendent George Tomyn feels the standards afford districts adequate leeway to create substantially different curricula while reaching the same goals.

“The Florida Standards we’ve adopted make sure all schools reach the same common goals for each student in each grade, while still giving us complete freedom to determine the curriculum to reach those goals,” he says. “Whether it be Shakespearian literature, the Constitution or some other piece of distinguished literary work that we should choose to use in our curriculum to meet that standard is left up to the states and the districts. The year-end assessments and end-of-course tests should soon give us reliable feedback on if we are reaching those goals using the methods and curricula we’ve chosen.”

But Why?

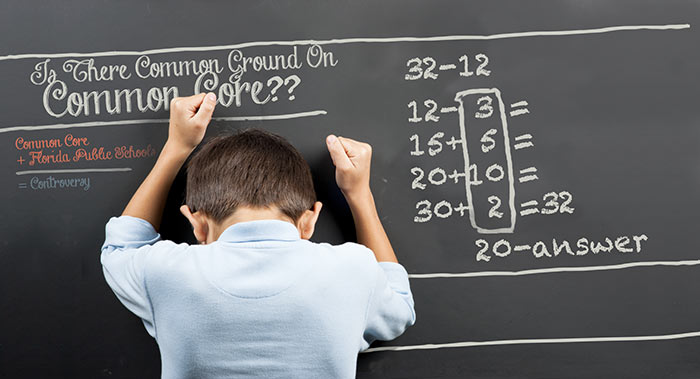

McCallum says Common Core concepts enable students to learn why math works… not just accepting the fact that 2 + 2 = 4.

“There are expectations that students be fluent in procedures, that they understand why those procedures work and that they be able to apply them to solve problems. The standards pay equal attention to fluency, understanding and applications,” he says. “They describe the expectations as a coherent whole, not in fragmented pieces. Students who have memorized many fragmented pieces have fragile knowledge, which crumbles when they are confronted with problems posed in a different way from what they are used to. Students who understand why the procedures they are using work and who see how all the pieces fit together are more likely to have a robust knowledge that lasts beyond the class they learned it in.”

Losito agrees.

“Teaching in high school is a bit different from teaching in elementary school using Common Core standards,” he says. “In high school, what we are seeing is that material is being taught at a ‘pushed up’ pace. Things that were being taught in 10th grade are now being taught in 9th. Younger students are expected to understand concepts they didn’t have to understand under the previous standards… but the real changes are in the elementary schools. Children are being taught a different way to look at numbers. And yes, it is true that this should give them a better number sense using this approach, especially when it comes to estimating and having some idea of what a correct answer should look like even before starting a problem.

“However, it will be three or four years before we begin to see if this concept is working,” Losito adds. “The students who are learning Common Core methods now will have to reach high school; only then will we begin to see if these changes have actually worked. Everything takes time… and we have to give Common Core time to prove itself.”

Tomyn thinks the standards are the real deal and that time will prove them out.

“When I took a look at the math standards as they are written, I understood why they have chosen this method to teach our children. Our generation did learn math in pieces, and we memorized certain ways of doing things, but we never fully understood the mechanics of math. I made As and Bs, but I just didn’t understand the why of what I was doing. Our children will have that ability.

“And, yes it will take a while to see if they are working, but remember, we’ve already been using standards in Florida for more than 15 years… this isn’t something brand-new.”

However, Marion County School Board District 1 member, Nancy Stacy couldn’t disagree more.

“The Florida Standards are an absolute disaster,” she says. “The math standards were written by mathematicians who have never taught one day of class in an elementary or high school. They sit around and come up with theories that they think will work and then experiment on our children with them. How can someone who has never taught a child know what is the best way to teach them? Look at how convoluted the process is to simply add two numbers together. It is nonsense.

“The true experts are the ones on the validation committees like Drs. Sandra Stotsky and James Milgram who believe Common Core will ruin our nations academic standing internationally,” Stacy adds. “I completely agree with them that the standards are totally inadequate and will set us back at least two years behind the world’s leading countries. This approach to math was already tried in Russia and in California, and it didn’t work then and it won’t work now. We will end up losing technology jobs to countries like China in the very near future.”

When Numbers Lie

When it comes to American students falling below international averages, McCallum feels that American students have the same abilities as international students who are scoring higher on PISA and that the long-term implementation of Common Core Standards will eventually prove this fact.

“I would not say that Common Core makes better students, but that it expects students to be better and it expects the education system to rise to that challenge,” he says. “The expectations of Common Core are equal to those of high achieving countries. American students have the same abilities as students in Singapore or Japan. If students in those countries can achieve the level of proficiency and understanding in Common Core, then so can ours.”

Losito goes one step further. He feels that the numbers aren’t truly indicative of where American students stand internationally.

“The American education system is one of the best in the world,” he says. “Step back and take a look. We are the most technologically advanced nation on Earth. I believe the reason it seems we are behind the rest of the world is because our education system teaches everyone. We don’t turn any child away from an education, and we don’t shuttle lower-performing students into vocational schools or allow them to simply drop out of school. We teach everyone regardless of their academic ability. Other countries don’t do this. You are only seeing the scores of their best students. I really think our system is the best, and I believe that when you factor all of this in, our students really are among the best and brightest in the world.”

Randy Osborne, Ocala resident and chairman of the Marion County Republican Party, an outspoken critic of the Common Core Initiative agrees.

“The numbers are simply not representative of the true state of education in the world,” he says. “Countries like China only show the scores of their best students, and we show all scores of all students. This is why Common Core was, and is, unnecessary. Our educational system was in great shape before the politicians started trying to make it better. If something isn’t broke, why fix it?”

Standardized Learning

All agree that standardization is helpful in assisting the education process, but does it have any drawbacks?

“i

would say standardization is helpful rather than necessary,” McCallum says. “If our expectations of students are shared across state lines, then resources can be shared also. And teacher preparation can be much more targeted to the mathematics that teachers will be developing in a given year. However, standardized tests do not assess everything a student knows… but they do give you some idea of how much students are learning. States spend on average something over $10,000 per student per year on education. It makes sense to spend a few dollars per student figuring out whether the investment is paying off or not. The promise of common standards is a common measuring stick that could be used to compare different teaching methodologies. However, I don’t think tests should be used in a crude way to make comparisons… there are so many other variables that might affect student performance.”

“Standardization is necessary,” says Losito. “It makes sure we are all on the same page and that education is uniform wherever you are in America. But the problem comes when the emphasis is on testing. Teachers tend to focus their teaching on the test, and when testing time comes, the students are under tremendous pressure to perform. In all this test preparation, we lose sight of the student and his or her need for a total education. We lose focus on instilling creativity through the arts, music, etc. It hinders our ability to turn out free thinkers with good ideas and a social conscience. We end up just looking for a number and miss out on creating a ‘whole’ child.”

“We live in a high-mobility state for students,” says Tomyn. “This means that we have lots of students moving here from other states, students moving within the state itself and students leaving the state to go elsewhere. Standardization ensures that if a student should leave their home in Oklahoma and move to Florida, they will be able to enter the classroom pretty much on the same academic level as the students around them. That’s very important for a state like Florida. If students can seamlessly enter a new classroom, then teachers aren’t required to spend extra time bringing them up-to-speed and the other students aren’t affected.”

High Stakes Testing

Everyone also agrees that year-end standardized tests should not be tied so closely to teacher performance and tenure, school grading and district funding.

“i

’m all in favor of holding teachers to expectations for their students’ learning,” says McCallum, “but we don’t know enough about all the variables and about the complexities of the education system to tie their evaluation directly to student test scores.”

“I believe in accountability, but there simply has to be a better way than basing teacher and school evaluations on a student’s score on a single test,” says Losito. “Some students simply don’t do well on tests, some kids may not have gotten to bed on time, some may not have eaten breakfast… there are just too many variables affecting a student’s score on a single test to use it to determine funding and performance evaluations.”

And evaluation methods have recently changed in Florida.

“I am very concerned that a student sitting down for a one-time test can help determine his or her teacher’s value-added performance score. But remember, this has been an ongoing problem for a while,” Tomyn says. “But things have changed a bit since the last legislative session. Before session, 50 percent of a teacher’s evaluation was based on student test scores and 50 percent was based on administrative observation. Now, 33 percent of the teacher’s evaluation is based on student performance and 67 percent is based on administrative observation. How does that observation take place? Here in Marion County, we train our principals to look for the qualities that make a teacher a good teacher, and we ask our principals to spend at least 70 percent of their time out of their offices among the teachers, observing them in the classroom and evaluating their strengths and weaknesses. No teacher evaluation model is going to be ideal, and all are going to be debated, but some method has to be used to determine how successful a teacher is in the classroom.”

Is It Political?

There may be basic disagreements between backers and opponents of the Common Core Initiative when it comes to the mechanics of the standards and their implementation, but Osborne, who has spoken extensively on the subject, takes his opposition a step further.

“c

ommon Core is purely a political ploy. Our education system was the best in the world before certain politicians began to try to change it,” he says. “Why did they want to change it? To gain more governmental control over our children. The way that Common Core math is taught is the perfect example. A parent today can’t sit down with his elementary-school-age child and help him or her with their homework. What parent can understand how or why it takes so many steps to just add two simple numbers together? Common Core forces the child to receive all their education from the school and from the teacher. And the schools have the ability to bend curriculum beyond just simple math or reading; they can introduce social or political issues into learning… and they do. I, and many others, feel this is just one more way for the federal government to control our and our children’s lives.”

Tomyn disagrees.

“Whenever I am challenged by someone who claims the standards are a government ploy to take over our children’s lives, I ask them to read the standards. The standards are simple. They outline exactly what our students need to know by the end of each school year at each grade level. They are well-defined and sound. There isn’t a hidden agenda. We aren’t mandated to use them, and we can teach them using whatever methods we choose. They are simply an outline.

“And here in Marion County, we have made an extra effort to help parents understand how the standards work. We have open houses… our teachers are always available to assist parents, so they too can understand how to help their children with their homework. We will take the time to teach the parents, so they can, in turn, help teach their children at home. We understand how vitally important it is for parents to be totally involved in their children’s educations, and we make every effort to keep them involved.”

It All Adds Up To Change

w

hether it’s a political ploy or simply what experts feel is the best way to teach our children, according to the experts, it looks as if standardization in education is around to stay for the foreseeable future. Unfortunately, it will take many more years to see if this set of standards is the best one… or even if it is a good one.