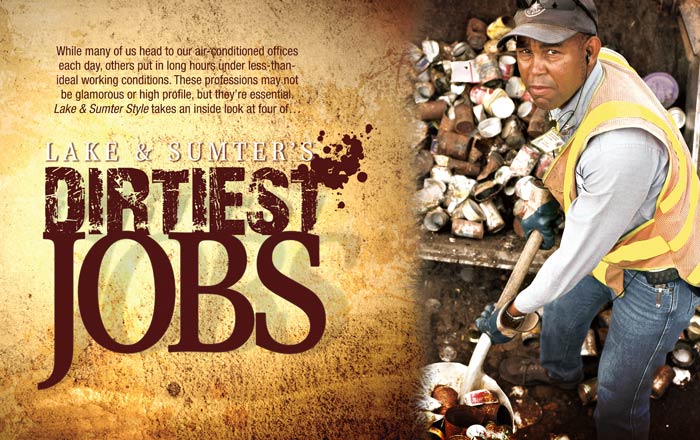

‘For A Dump, We’re Pretty Clean’

Before heading to the landfill, Sumter County’s trash—or the vast majority of it—makes a pit stop at Jimmy Wise’s office.

The solid waste facility off rural CR 529 in Lake Panasoffkee shouldn’t be confused with a landfill, which is a graveyard for garbage. Consider the trash here on a layover.

Above: Though trash abounds at Sumter County’s open-air waste facility, Operations Coordinator Jimmy Wise and his team haven’t received an odor complaint in years. Below: On any given day, John Moody and his co-workers load 75 to 100 tons of the county’s trash onto semis headed for Holopaw Landfill.

By the Hefty bag and by the truckload, from rural residents, the City of Bushnell, and nearby Coleman Federal Prison, garbage is dropped off at this Sumter County waste hub six days a week. And every day, between 75 and 100 tons of it is loaded onto semis and shipped to Holopaw Landfill, south of Kissimmee.

What happens between the dumping and the loading falls under the watchful eye of Operations Coordinator Jimmy Wise and his team of eight Department of Environmental Protection-certified workers. Their goal is two-fold: sort as many recyclables out of the trash and get what’s left behind out as quickly as possible. The speed with which they accomplish this task may explain why, remarkably, the open-air facility doesn’t smell.

What happens between the dumping and the loading falls under the watchful eye of Operations Coordinator Jimmy Wise and his team of eight Department of Environmental Protection-certified workers. Their goal is two-fold: sort as many recyclables out of the trash and get what’s left behind out as quickly as possible. The speed with which they accomplish this task may explain why, remarkably, the open-air facility doesn’t smell.

“We haven’t had an odor complaint in over four years,” Wise says. “I think you’ll see that for a dump, we’re a pretty clean place.”

He’s right. The work may be inherently dirty, but the facility runs like a well-oiled machine. From eight in the morning until five at night, a steady stream of cars—some 200 a day—loaded down with bulging trash bags, cans and plastic bottles, and bundles of old newspapers crosses the weigh station scales and snakes through the facility, the drivers stopping at the appropriate bin to pitch an item.

The facility encourages recycling. Cans, cardboard, newspaper, milk jugs, and soda bottles all have separate disposal containers, as does lawn waste, scrap metal, motor oil, electronics, and car batteries. Wise’s team accepts large recyclables, too, which explains the pair of beat-up washing machines and the haystack of old bicycles by the 20-yard dumpsters. The items are sold to Ocala Recycling and to Trademark Metals Recycling in Tampa, with the profits going right back to the facility to help pay salaries and maintain equipment.

“We operate as an Enterprise Fund, which means we try to operate off of the money we bring in,” Wise explains. “We get a Small County Consolidated Solid Waste Grant, but we don’t get money from the general fund or county taxes.”

Watching residents drive around the property, an obvious question comes to mind: Why doesn’t everyone in the county have curbside pickup?

“There’s an old joke—Sumter County doesn’t do curbside pickup because we don’t have curbs,” Wise deadpans. “We’re pretty much still a rural county.”

A garbage truck from Bushnell, which does provide curbside service, bypasses the residential disposal up front and heads to the tipping floor—a large, three-walled warehouse—for unloading. There, a worker operating a front loader with solid-rubber tires—“No flats,” Wise explains—pushes the incoming trash into manageable piles and then shovels buckets-full onto a waiting semi, headed for Holopaw.

“The loader bucket has a scale, so he knows how much he’s put on the truck,” Wise says. “These trucks average about 25 tons a load.”

Meanwhile, another employee works on-foot, directing traffic, keeping floor drains clear for liquids, and pulling large recyclables, such as tires and cardboard, from the heaps. He also removes unacceptable items—florescent bulbs, half-full paint buckets, and generally “anything with a skull-and-crossbones on it.” Glancing at a mangled mattress and box spring leaning against the building’s far wall, Wise nods: “We get everything here.”

Most importantly, the county gets employees here who are as loyal as they are hardworking. Altogether, these men have given nearly 100 years to the facility, and Wise, who contributes a decade to that total, hopes to keep working alongside them until the day he retires.

“I’m really proud and blessed to have a good crew,” he says. “They’re dedicated to their job.”

‘The Heat Is A Lot To Take’

Roofing is back-breaking work, Bud Gordon admits, especially on a scorching summer day.

Roofer Terry Mixon takes a much-needed refreshment break while working on a recent job. The temperatures on a roof can easily exceed the 100-degree mark during Florida’s summer months.

Sweat drips from the brim of his nose as the roofer hunches over, 20 feet above the ground with no safety belt. His claw hammer removes fasteners, one by one, from the rooftop materials in preparation for a re-roofing job. The noon hour has yet to arrive, and the men are already exhausted, sweaty, and sore. On days like these, nothing feels as good as a small section of shade and a quick swig of ice-cold Gatorade.

Ninety-five-plus degree air temperatures, the scorching Florida sun, and dangerous elevations are just a handful of the challenges Central Florida roofers face on the job. Bud Gordon and his group of talented roofers at Bud Gordon Roofing take the conditions in stride, though.

Bud Gordon runs his successful Lake County roofing business with the help of his dedicated and talented staff.

“Yes, the heat is a lot to take, especially when you factor in that the temperature on the roof is probably closer to 120 degrees,” Bud says. “For me personally, though, demolition is the most challenging part of being a roofer.”

Consider that the roofing materials on an average 3,000-square-foot home likely contain close to 17,000 fasteners. During a re-roofing job, each of those fasteners has to be removed by hand. The process can create blisters and calluses on even the most athletic of hands.

As for the heights, Bud normally doesn’t give them a second thought—unless the morning is damp or footing conditions are not solid. Then the site can be an accident waiting to happen.

“Wet roofs and shingles with loose granules can easily cause a roofer to lose his footing,” he says. “Rotten wood decking also poses an increased risk.”

Bud should know.He admits to falling off a roof or two in his time.

“Once I was trying to show the guys how to put felt down,” Bud recalls. “I got to an area where there was dust on the roof and slipped. I hit a two-by-four with both feet thinking it would stop me from falling over the edge, but it didn’t. On the way down, I remember looking and seeing a half cinder block. I was lucky enough to be able to quickly spread my feet to straddle the block.

“It probably took one and half seconds to hit the ground,” he continues. “But it feels much longer when you’re visualizing the what-ifs on the way down.”

‘Nothing Goes To Waste’

Twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, Jerrill Robison and his operators reclaim millions of gallons of Leesburg’s raw wastewater.

Cleaning the Leesburg/Canal Street Wastewater Treatment Facility’s clarifiers is just one of the tasks that keep Chief Plant Operator Jerrill Robison and his employees busy.

The sign at the plant’s entrance is faded but the warning is still legible: “Obey Lifeguards.”

“You’ve got to have a sense of humor here,” Jerrill Robison says with a chuckle as he walks past a large basin of churning brown wastewater.

Clearly, the Leesburg/Canal Street Wastewater Treatment Facility is no place for a swim, but a little well-placed humor helps keep things in perspective for the chief plant operator and his crew of 11. In fact, they provide a vital public service, however unappreciated their work might be.

Business and household wastewater from 161 lift stations flows into the facility every day, and the responsibility of transforming that raw wastewater into reusable water falls to Robison’s dedicated team.

“Our typical flow is 1.5 million gallons a day,” Robison says.

After preliminary treatment removes rags, sand, and the errant set of car keys that have made it into the sewage system, the wastewater enters an aeration basin where biological oxidation—courtesy of Mother Nature and motorized mixers that agitate the water—takes over.

“The purpose of the mixers is to establish dissolved oxygen in the ‘mixed liquor,’” explains Robison, using the industry term for the wastewater at this stage. “We create an environment for beneficial bacteria to perform the work for us. It takes up the organic material that’s in the water.”

Following two to three days of bacterial scrubbing, the water heads to a large sedimentation tank on-site called a clarifier.

“The mixed liquor flows into the clarifier’s center ring, and the solid items settle to the bottom,” Robison continues, then points to the small grooves in the top of the ring. “The clear water cascades over the top through these notches, into this trough, and then out for further treatment.”

Over time, material accumulates at the bottom of the clarifier and has to be removed, which requires a 1,500-gallon sewer jet truck, a large suction hose, and plenty of old-fashioned elbow grease from the crew. While the hose skims the surface of the muddy bottom, sucking up matter from the waterless tank, two hazmat-suited workers climb down into the clarifier and use high-pressure water guns to break up the solidified sludge. In all, the cleaning takes several hours and fills three truckloads.

“When the truck is full, it’s dumped at our drying bed, which has a drain under it,” explains Plant Manager Rick Harris. “The solids stay on top of the rocks and the water percolates down to be recaptured and sent back through aeration for treatment again.”

The process brings new meaning to the adage, “Waste not, want not.”

“Nothing goes to waste here if we can help it,” Robison agrees.

Every aspect of the plant—from pump function to chemical levels to wastewater intake—is carefully monitored and controlled by computers in the main office. Robison’s team can watch flow fluctuations by the hour, from the usual peak between six and eight in the morning to the second wind around noon. Holidays such as Christmas, Thanksgiving, and St. Patrick’s Day keep the plant particularly busy, and even the Super Bowl has a measurable effect on flow here.

“You can almost see when the commercials are,” Robison says, pointing to a graph of flow data from February 1 on his computer screen. “About the end of May, flow drops off,” he adds, referring to the annual exodus of snowbirds.

Though the work here is dirty, the facility is a model of efficiency, and Robison, a 27-year veteran of the wastewater industry, has a very good explanation for its competence.

“Because,” he says proudly, “we’ve got a good team.”

‘Cleaner Than A Lot Of People’s Kitchens’

For the workers at Uncle Donald’s Farm in Lady Lake, nothing says “good morning” quite like the smell of farm animals and raw meat.

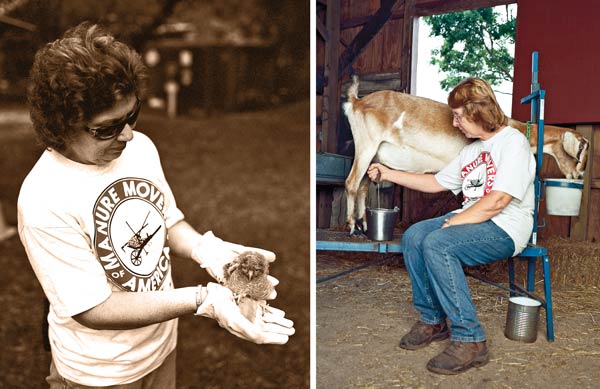

Rain or shine, in high heat or chilling cold, Donna Morris’ workday starts around seven every morning. Over 300 animals, from cats and donkeys to cougars and reptiles, await her housekeeping skills at Uncle Donald’s Farm in Lady Lake.

(L–R) Valerie Brown, Sue Seigworth, Donna Morris, and Beth Morris pause for a photo while recently working at Uncle Donald’s Farm in Lady Lake. Pitchforks, shovels, gloves, and wheelbarrows are necessary “office” supplies at the farm.

“Our job is to keep the animals—and the public—safe,” she says.

For the farm’s co-owner, the day begins in the wild animal area. Depending on the animal, her cleaning duties can be as simple (albeit unpleasant) as scraping animal droppings using an old flat shovel or as difficult as corralling big cats into holding pens.

On this particular day, “Marty,” the farm’s popular Florida panther, has relieved herself in her water dish, the stench wafting through the air. Even the cool 65-degree temperature can’t hide the smell. Lounging lazily in a holding pen, Marty watches with only mild interest as Donna uses a water hose to blast the contents of the bowl onto the pavement before scooping it up with a shovel.

Another pleasant chore for Donna? Cleaning up the wild animals’ dinner “leftovers.” Flies and gnats circulate around what used to be three to five pounds of raw meat. Donna jokes that the cats aren’t picky.

Left: As a co-owner of Uncle Donald’s Farm, Donna Morris has a hand in every aspect of the farm’s workings. Here she carefully handles and cares for a newly born owl. Right: Beth Morris milks a goat at Uncle Donald’s Farm in Lady Lake—just one of the many “hands-on” jobs that need to be done on a daily basis.

“Chicken, beef, pork, lamb, they’ll eat anything,” she says. “Often, the panthers or the coyotes like to hide their food and wait until it gets kind of rank before they eat it. It’s not very pleasant when we discover their old food hidden under leaves or sticks. Sometimes it cleans up and other times it falls apart.”

Donna recalls one evening when a raccoon had a “grand time” eating his meal.

“We gave him a cooked turkey leg and he proceeded to smear the food all over his enclosure,” she says. “That was really gross to clean up.”

Though the animals may make a mess of their food once they’re served, the workers go to great lengths to ensure the food is properly stored before mealtime.

“The animals’ kitchen is probably cleaner than a lot of people’s kitchens,” Donna says. “We have two freezers and a fridge to keep produce and meat fresh and safe.”

After completing her rounds at the panther cage, Donna makes her way to the river otter enclosure. “Weasel,” a normally playful otter with mischievous dark eyes, sleeps soundly in the shaded rafters as Donna drains his in-ground pool and cleans the sopping leaves brought in by recent rains.

“The pool is drained every five days to ensure no mold grows,” Donna says. “We can’t use chemicals, so we have to keep it clean with good old-fashioned elbow grease.”

As Donna continues her work to the soundtrack of screeching sand hill cranes and gobbling turkeys, her fellow employees are hard at work elsewhere on the farm.

“We have to get in the cages with the animals,” says Sue Seigworth. “Close-toed shoes are a must. For me, the chicken pens are the worst. You just never know what condition they’ll be in when you get there. They don’t smell pleasant.”

As hard as it is to believe, the chickens make more of a mess than the farm’s 900-pound pig, “Wilbur.”

“He might smell really bad,” Sue says, “but he’s actually a relatively clean animal.”

The workers take turns putting Avon’s Skin So Soft on Wilbur to cleanse him, ensuring he’s fresh for his daily visitors. How’s that for an enjoyable job?

By 10, the employees have been cleaning and scrubbing for nearly three hours. In preparation for a visit from a large group of elementary school children, Sue uses a pitchfork to scrape the old hay, along with the inevitable animal droppings, from the chicken coop. The scraped material will eventually make its way to the farm’s compost pile to be used as fertilizer. The wild animal waste, on the other hand, is removed and buried.

As the buses pull up to the farm, the elementary kids run through the rows of cages and pens, oohing and aahing at the animals and tossing handfuls of feed to them, fully unaware of the hours of prep work that went into making the animals presentable. For Donna, Sue, and the others, the fun will begin again at daybreak.

“We want our facility to look and feel like a farm,” Donna concludes, “but not smell like one.”