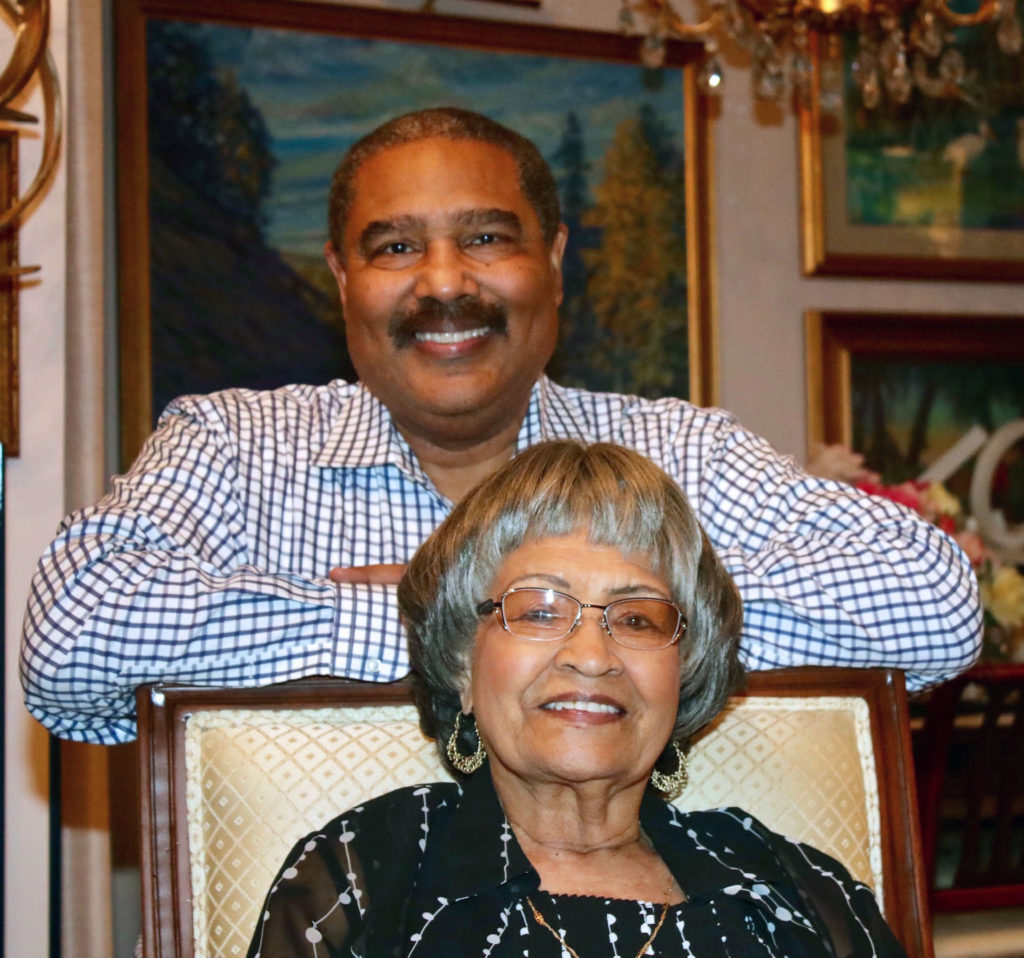

Longtime Ocala/Marion County educator Juanita Cunningham was awarded the key to the city of Ocala in September. That honor joined the previously declared Juanita Perry Cunningham Days on July 1st, 2005 and June 18th, 2015. But perhaps the biggest accolades should be given for raising her family to rise above racial discrimination and achieve their own successes. Her son and family spokesman James C. Cunningham Jr. shares the story of this remarkable family.

Juanita Cunningham, the 95-year-old matriarch of her family, and her late ex-husband James, squared their shoulders against the headwinds of the Jim Crow era, prevailing to live inspiring and meaningful lives. Despite the odds against them, Juanita and James parlayed higher education to a better life for themselves, their children and their community.

“Growing up when they did, my parents were well aware of the social inequities for the Black community,” says James C. Cunningham Jr., 65, the couple’s eldest son, who had a front-row seat to his family’s journey. “But that did not deter them. And they made sure we understood that the best was expected from my siblings and me. The message wasn’t if we were going to college, it was where we were going to college.”

The Cunninghams led by example. Juanita earned degrees in elementary education and education administration and James Sr. garnered a degree in mortuary science. As for their children? James Jr. and his brother Courtney earned law degrees while sister Renee has a master’s degree in sociology.

James Jr. proudly points out that his parents paid for their educational pursuits.

“Through education, our family was transformed and uplifted,” he says. “We were born in and of a certain time. But we overcame a lot of obstacles as Black people to be part of the change that came out of that time. And it all started with my parents.”

Humble Beginnings

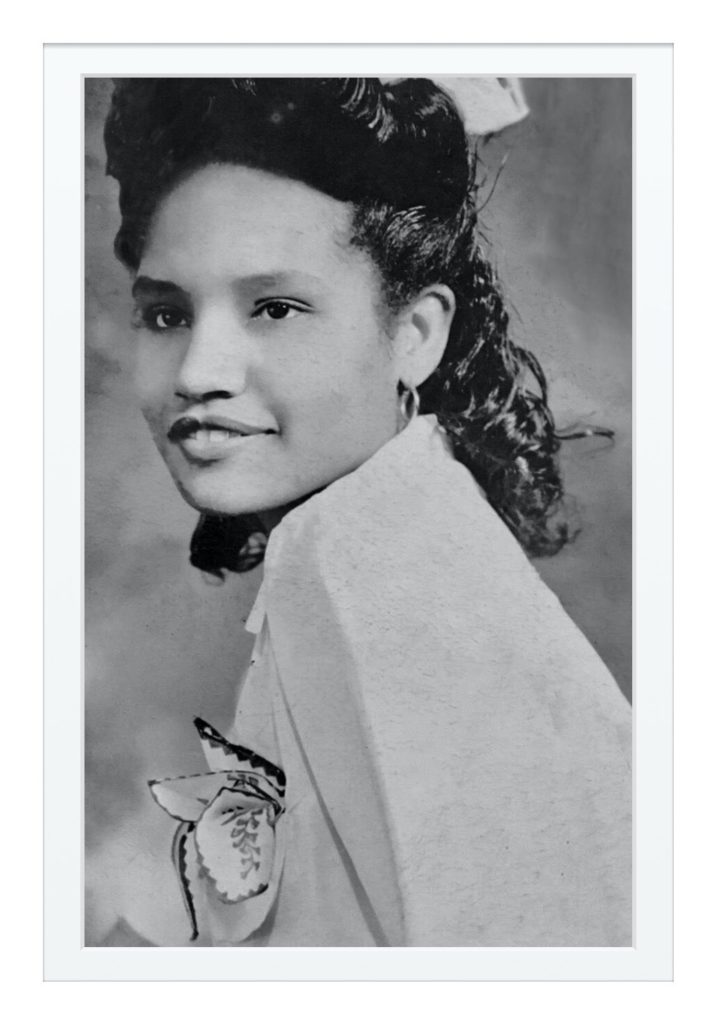

Juanita Perry was born in St. Petersburg on June 18th, 1925 and, while still an infant, her mother moved to Hawthorne in Alachua County. There, Juanita grew up around her stepfather, six siblings and her grandfather, who was the can-do patriarch of the family. In the summers, Juanita worked in the nearby fields, picking beans.

James Jr. explains, “The children in Black families were expected to work to help earn money for the family. It was just the norm then.”

From first to 12th grade, Juanita attended the segregated Shell School and it was there that a teacher took a special interest in her.

“Mildred Greene was my mother’s fifth-grade teacher and she was the one who told my mother that she could and should go to college,” explains James Jr.  “Mrs. Greene planted that notion in my mother’s mind, which proves that just one person, particularly a teacher, can make a difference.”

“Mrs. Greene planted that notion in my mother’s mind, which proves that just one person, particularly a teacher, can make a difference.”

But college would have to wait for Juanita. Right out of high school, she attended the Sunlight Beauty School in Miami. Then she came back to Hawthorne where, according to James Jr., her grandfather built her a little building for her hair salon on his property. And Mrs. Greene became one of her regular customers.

“My mother told me that every time Mrs. Greene came to get her hair done, she would say, ‘Juanita, you need to go to college. You don’t need to press hair all of your life.’ Mrs. Greene just wouldn’t give up on my mother,” says James Jr. with admiration.

But Juanita’s college aspirations were soon deferred by love when she met James Sr. at, of all places, a funeral.

“In the mid-1940s, my father worked for Chestnut Funeral Home in Gainesville while my mother was operating her beauty parlor in Hawthorne,” James Jr. explains. “One of my mother’s many talents was that she had a beautiful soprano singing voice and had been asked to sing at a funeral in Hawthorne, which was conducted by Chestnut Funeral Home. My father was smitten and while everyone was at the cemetery for the burial, he asked my mother if he could call on her. She said yes, he courted her and they were married in 1946.”

James Jr. recalls asking his mother once why she married his father, saying she answered, “He was an ambitious man and he was going places.” He adds, “Turns out, it was a team effort and they went places together.”

Education Mattered

The Cunninghams moved to Ocala in 1951 and James Sr. went to work for Chestnut Funeral Home there. But as Juanita so astutely pointed out, James Sr. was an ambitious man and he wanted his own funeral home.

“My mother stopped pressing hair as Mrs. Greene suggested, but instead of going to college, she put my father through college,” James Jr. reports. “She did domestic work to pay for my father to attend Eckels College in Pennsylvania and get a degree in mortuary science. In 1952, my father and his brother Albert established Cunningham Funeral Home in Ocala.”

Not only did the Cunninghams start a business in 1952, they also started a family, with daughter Renee being born. James Jr. would come along in 1955 and Courtney in 1962. Shortly after James Jr. was born, Cunningham Funeral Home was doing well enough that Juanita could finally go to college.

“At 30, my mother went to Bethune-Cookman College in Daytona Beach, staying there during the week and then coming home on the weekends,” according to James Jr. “The plan was that Renee, who was 3, and me, still a baby, would stay with our grandmother. But I wouldn’t stop crying, so my mother just took us to school with her. She would leave us outside the classroom and other students would check on us, making sure we were OK. I know that sounds like something crazy to do, but it was an all-Black school and the Black community took care of each other.”

“At 30, my mother went to Bethune-Cookman College in Daytona Beach, staying there during the week and then coming home on the weekends,” according to James Jr. “The plan was that Renee, who was 3, and me, still a baby, would stay with our grandmother. But I wouldn’t stop crying, so my mother just took us to school with her. She would leave us outside the classroom and other students would check on us, making sure we were OK. I know that sounds like something crazy to do, but it was an all-Black school and the Black community took care of each other.”

In 1958, Juanita finally made Mrs. Greene’s advice come to fruition, graduating with a bachelor’s in elementary education. None other than Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered the graduation commencement speech.

“My mother was obviously inspired by Dr. King and came home not only with a degree, but with activism on her mind as well,” he shares. “And she and my father were on the same page there too.”

Juanita’s first teaching assignment was at the segregated Stanton

Elementary and High School

in Weirsdale, just south of Ocala. She then taught at the all-Black Howard Elementary School. Meanwhile, James Jr. was growing up in a time of segregation that was grudgingly giving way to desegregation.

“My parents explained to us that the law wouldn’t permit us to do certain things, like use a restroom designated for whites only,” he notes. “But that didn’t mean they weren’t trying to change those laws. In 1963, my father participated in the March on Washington. And he was part of these mass meetings to organize civil disobedience at Covenant Baptist Church.”

Time For Change

Slowly but surely, desegregation moved into the Marion County education system.

“From first to fifth grade, I went to all-Black schools, Madison Street Elementary and Howard Elementary,” James Jr. recalls. “But in 1965, the Freedom of Choice program was instituted in Marion County and my parents chose Eighth Street Elementary for me. I was one of only five Black students and the school district didn’t provide us with school bus transportation. My father and another parent took turns carpooling us to and from school.”

James Jr. would then go to Osceola Middle School in the seventh and eighth grades, before moving on to Vanguard High School, where he graduated as class president in 1973. By the time he went to the University of Florida (UF) to earn a political science degree in 1976, his mother had also gone back to college.

James Jr. would then go to Osceola Middle School in the seventh and eighth grades, before moving on to Vanguard High School, where he graduated as class president in 1973. By the time he went to the University of Florida (UF) to earn a political science degree in 1976, his mother had also gone back to college.

“My mother attended Nova University, which was located in south Florida. The professors would come up to Gainesville on Saturdays to teach and that’s how she got her master’s in education administration in 1976,” he shares with obvious pride. “She then became what was called the dean of girls at Vanguard High School, which was later changed to assistant principal. After that, she became the first program director/principal of Howard Academy Community Center. She retired in 1991.”

And James Jr. adds, “Just like Mrs. Greene had inspired her, my mother inspired her students. She still has past students who stay in touch with her to this day.”

Before retiring, Juanita spearheaded the program to have free hot lunches served in schools. She also was a founding member of the local chapter of Altrusa International, a nonprofit organization dedicated to making communities better through service. One of Juanita’s pet projects with Altrusa was having members, and others from the community, visit elementary schools once a year to read to the students. The Juanita P. Cunningham Bookshelf is located inside the Tools 4 Teaching room at the Public Education Foundation of Marion County. There also is a Juanita P. Cunningham Endowed Scholarship through the College of Central Florida Foundation, which is awarded annually to an African American student or graduate of Vanguard High School.

As for James Sr., he made history in 1975 by being the first Black man in 86 years to be elected to the Ocala City Council. He would also serve as city council president and was re-elected in 1979 and 1983.

“My father was instrumental in the city annexation of the section of West Ocala from Martin Luther King Jr. Avenue to I-75,” asserts James Jr., who earned his law degree from UF in 1978 and became the first Black law clerk with the Florida Supreme Court. “When he was first elected to the city council, that part of West Ocala was underserved; there were few paved streets and no city water. My father helped change all of that.”

After being married for 38 years, Juanita and James Sr. divorced in 1983 and James Sr. died of a heart attack in 1985.

“My parents always made sure that their children had as many advantages as possible. They took us to events that often times we were the only children there,” remembers James Jr., a Miami-based retired commercial litigation lawyer who now creates steel sculptures on commission. “They believed it was important that we got a big-picture view of the world and saw what was possible for us through education and hard work. I like to think that my family is an example of what happens when people are free to be who they are.”