Sumter County’s culture of agriculture has been disappearing at an alarming pace, only to be replaced by a new cash crop of housing developments. To satisfy the lifestyles of those new residents, the old way of life is getting paved over with bigger roads, shopping centers, and fast food restaurants. But as long as customers are ordering hamburgers from those restaurants, there will be a need for cattle—and cowboys. Meet five of this latter group. They’re…

A Cowboy Roundup: (l to r) Ricky and Angela Rollison, Kenny Hicks, Chandler Holt, Coy Mueller, and Jeff Jowers relax after working all day at the Rollisons’ ranch.

As late as the 1970s, Florida was the second-largest cattle producing state in the nation. It was third in its number of Professional Rodeo Cowboy Association rodeos. So where’s the beef now? It’s grazing on side roads off of US Highway 301. It’s sold at the Livestock Market in Webster every Tuesday from noon to night, until all is sold.

Every cowboy covered in the pages to come has covered thousands of miles of this land on horseback, from The Villages to Marion County and beyond. They remember a time when only two or three cars would pass over 466A all night. Now, during rush hour, that many pass by in as many seconds. This is a cowboy’s story.

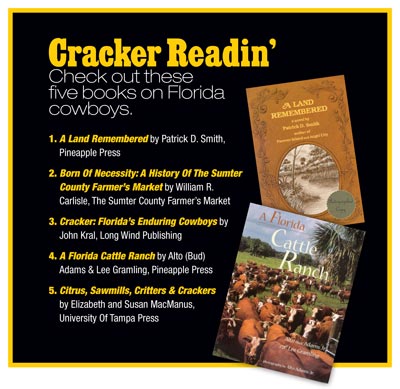

‘A Happy Man’

‘A Happy Man’

A hard rain is pounding on the tin roof of the perfectly kept barn at the ranch Ricky Rollison owns in Oxford. An inviting chair-swing sways. In the outside living room, a fire pit, comfortable chairs, and a television make for a relaxing end to a long day of doing what the sign on his board rail fence says—yes, breakin’ and trainin’ fills the hours.

“I was raised in the woods in Dixie County on the Gulf Coast,” Ricky begins. “I never left until I was about 15. I worked woods cows but wanted to work on a ranch.”

In 1975, Ricky heard the Bailey Cattle Company was hiring. From daylight to dark, he worked for $92 a week.

“They treated me like family,” he recalls. “I rode a lot of young horses and people heard about it.”

That experience is what honed Ricky into the excellent horseman he is today.

“Florida horses were raised to be tough,” Ricky says. “If they didn’t make it, we’d find something else for them to do, like being a trail horse.”

Finding what a horse does well and how he does it is why Ricky has excelled professionally, and although Quarter Horses are a cowboy favorite, Ricky has a broader view of breeds.

“Horses are like people—they’re all different. I can read their mind and pick their brain,” Ricky remarks with compassion. “I take all horses in—dressage, jumpers, Arabians, you name it. Every horse deserves a chance.”

People who need a horse for a specific purpose know Ricky won’t advise them to put a saddle on just anything.

“I stand behind what I do,” Ricky states. “If he’s a horse I can’t help, I don’t charge them.”

He also procures cattle.

“I run around 200 brood cows,” Ricky says, “My wife, Angela, and I do most everything on this place. She can drive a fence staple in a fence better than anybody.”

A little background—a cowboy staple is a slippery, U-shaped piece of pointed metal that can lame a horse if it flies away and lands hidden in the grass. For this reason, horse fencing is a serious skill.

Most of their children are grown and gone, but today, granddaughter Savannah, 6, is helping “Paw-Paw” train. She is fittingly on the lead horse. It is evidence the tradition will continue.

“Ten years from today, I’ll still be riding horses if the good Lord’s willing,” Ricky forecasts. “That’s my life. That’s all I do. If I get hurt bad and pass on riding a horse, I’ll go a happy man.”

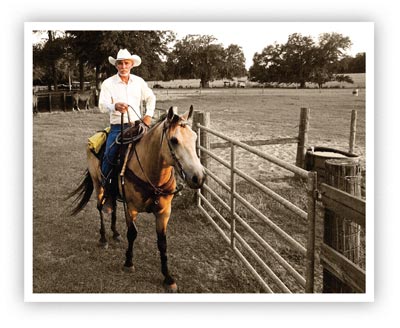

‘A Good Horse Is Like A Good Truck’

‘A Good Horse Is Like A Good Truck’

Jeff Jowers is a cowboy of few words but of much value to ranches in Sumter County. His father, Donny Jowers, raised him to be that way. It’s been an inside joke that cattlemen had as many children as they could so they would have free ranch hands. They started them early and worked them late. Jeff was no exception.

“Daddy started ranching when I was in high school,” Jeff remarks at the end of a long workday. “I never wanted to do anything else. I’ve done it for so long.”

And it’s hard, dirty work. Ranching isn’t glamorous, like the silver screen suggests. It’s not all riding horses and rounding up cattle for the big sale.

But Jeff’s pretty wife, Jenilee, and his son, Brody, are happy to be a part of carrying on the family tradition. If you ask Jeff how many generations his family goes back, his reply is simple.

“I don’t know. A long way, I guess.”

He shoots straight about the future of living off the land in Florida.

“Everybody’s buying up land to build houses,” Jeff laments.

But until all the land is gone, you’ll probably see him atop his horse, Legs, putting in a solid day’s work.

“A good horse is like a good truck,” Jeff shares. “The less you have to work with them, the faster your day goes.”

‘A Way Of Life’

‘A Way Of Life’

The sun is going down across US Highway 301, but for Rusty White, the day is far from done. The hounds are howling in their pens, and Rusty is working on a pre-conditioning cow pen with friend Randy Croft. But Kenny Hicks hasn’t shown up yet. It’s no surprise. They know he’ll get here when he gets here. The men are sinking fence posts and running string to keep it straight. Welcome to recycling, the cowboy way.

“This barn,” Rusty explains, “came from Mr. Bailey when they tore the place down.”

You see, cowboys have been “green” long before the term became popular. Likewise, Rusty was here long before Sumter County became a hot spot to call home.

“I watched this county road go from a dirt-rut road to clay to asphalt,” Rusty recalls. “Thirty years ago, you might see two or three cars pass by. Now it takes 15 to 20 minutes to get a horse trailer out in the morning.

“I used to ride across this county on horseback,” he continues, “and knew everybody I saw.”

Mornings start early. Evenings like this one mean you need to turn the lights on in the barn so you can work. Young son Ethan is with his dad and his dog.

“This is not a living,” Rusty states. “This is a way of life.”

But The Villages have changed that way of life.

“I don’t blame anybody for cashing in their land,” Rusty remarks. “It made a lot of people rich, and it’s progress. I guess they’ll just keep planting houses.”

Yes, Florida’s new cash crop is houses, but the economic downturn has slowed things down a bit. That’s okay with Rusty. The slower the pace of progress, the longer Rusty can enjoy his traditional way of life.

“I was born right here in Oxford,” Rusty reminisces. “Mom and Daddy had a working Quarter Horse breeder operation.”

Randy Croft, who smiles when asked if he’s still waiting for Kenny Hicks, interjects, “The Florida we knew isn’t Florida anymore. There are still big ranches in South Florida, but work is hard to come by here.”

When they do come by work, they have their own brand of time-shares.

“If someone needs a crew of three guys for three days, we change up the guys so everyone gets work,” Randy explains. “We stick together.”

Though Rusty has done other things for a living, he’s always “gone back to cowboying.” He also trains cow, deer, and hog dogs from Sumter County lines that date back generations.

“Some people don’t have a bond to the land, I reckon,” Rusty admits. “But I’m proud to be a Cracker.”

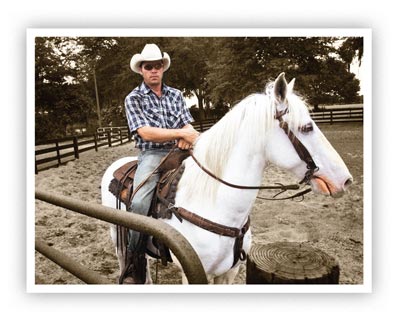

‘Give Respect’

‘Give Respect’

Coy Mueller, 27, is allowed a short break from working for Ricky Rollison, breakin’ and trainin’ horses. He’s one of a few young cowboys keeping old traditions alive. He was “born into” a Dade City ranching family—his father, Joe, operated M&M Cattle Company and Circle B Meat Packing and his uncle is a livestock broker.

Ask what he envisions for Sumter County cowboys in 10 years and Coy doesn’t have to ponder long for an answer.

“We’ll probably have half the cowboys,” Coy says with a sigh. “The most cowboyin’ some guys do is at rodeos. They don’t go out and work cows anymore. The only realistic events in rodeo are team roping and calf roping.”

In rodeos, Coy ropes and rides bulls. In ranch rodeos, he rides wild colts and does team branding. Ricky is cracking a whip nearby to get the horses accustomed to the sound that gave the name to these living legends.

Ask him what he sees 20 years ahead and he shakes his head.

“There will probably be no place to work,” Coy sadly projects. “Some people forget their great-grandparents ate beef. Americans survived by growing their own vegetables and meat; they slaughtered animals. It may not be politically correct, but it was part of life. It hurts the business because people believe animals are being mistreated, and they’re not.”

You may not agree, but it’s something to think about when you’re at the drive-thru ordering a hamburger or the next time you open a can of pet food.

“Right now it’s hard for me to get a job doing what I know how to do,” Coy continues, “because there’s nowhere for a young guy to work.”

The current system involves a hierarchy of hired hands.

“Young guys do the grunt work, building fences and riding colts,” Coy explains. “You move up into penning cows and day working. Older guys keep going because ranches are smaller. Big fence companies have taken away those jobs. Young guys have to settle for something else.”

Coy says he had those jobs, but was never happy.

“When you’re raised on a ranch,” Coy says, “you have a certain mentality. Things are slower. You’re taught to take your time and make sure everything is done right the first time. Ricky is passing what he knows on to me.”

The advice he passes on is to preserve the heritage.

“If you own a family ranch, stick with it and keep to your roots,” Coy suggests. “Give respect to the guys who did it before you.”

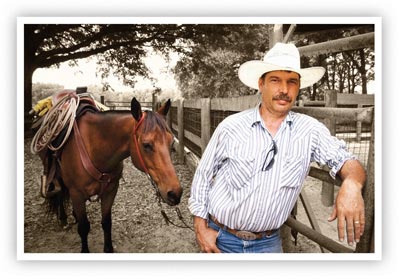

‘The Baddest Ass Cowboy Around’

‘The Baddest Ass Cowboy Around’

When you finally track down Kenny Hicks, it’s time to cowboy up. I take notes on the back of a tractor tire, with a puppy chewing on my jeans ‘hem. You catch Kenny when you can.

“It’s a good thing I’m late ‘cause they need a head start,” he laughs. “I’m the baddest ass cowboy around—and you can print that!”

Bonifay-born and one of six kids, Kenny was ranch-raised. His father was a horse trader.

“Cowboyin’ came first,” Kenny says. “We had one Paint stallion that bucked. I could ride him at two. A rodeo announcer told the crowd anyone that could ride him could have $250. He bucked everyone off but me.”

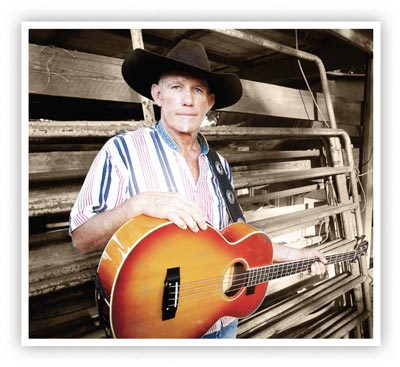

The incident was Kenny’s early foray into show business. Today, he keeps another tradition alive as a singing cowboy, though he’s far from the Roy Rogers variety. His band, Justin Heet, has been around for more than 30 years and a new album is out with another on the way. Steeped in R&B, country rock, and lots of well-written originals, Rick Stott, Bobby Croft, Tony Manna, and Mark D’Aigle make up the non-cowboy components of this local favorite at the Leesburg Bikefest and other venues.

Respect is something Kenny has earned, with a joke or two along the way. Though not often punctual these days, tardiness was not a luxury he was afforded when his family moved to Lake County in the ‘60s. Kenny was 10 when he began working cattle for the Bailey Cattle Company and credits that family for starting him in the profession he loves. He also credits Miss Barningham, his elementary school music teacher in Fruitland Park, for teaching him about music.

“I worked all day and sang all night,” Kenny remembers. “I’d get a 20-minute power nap and be good to go. I can still do it now.”

Kenny sees the future of cowboy work in Central Florida as something that will soon be in the past—gone but hopefully not forgotten.

“There’s just no cowboy work anymore,” Kenny explains. “You have to love it. It’s hard work, long hours, and no money. I would steer a young person in another direction.

“But,” he continues, “how many people get to do two things they love in life?”