Some girls want to be models. Some girls dream about seeing their image in magazines. Many actively seek out fame and fortune. And then there are those who distinguish themselves in other ways and find themselves in the path of an opportunity that creates a legacy beyond their expectations.

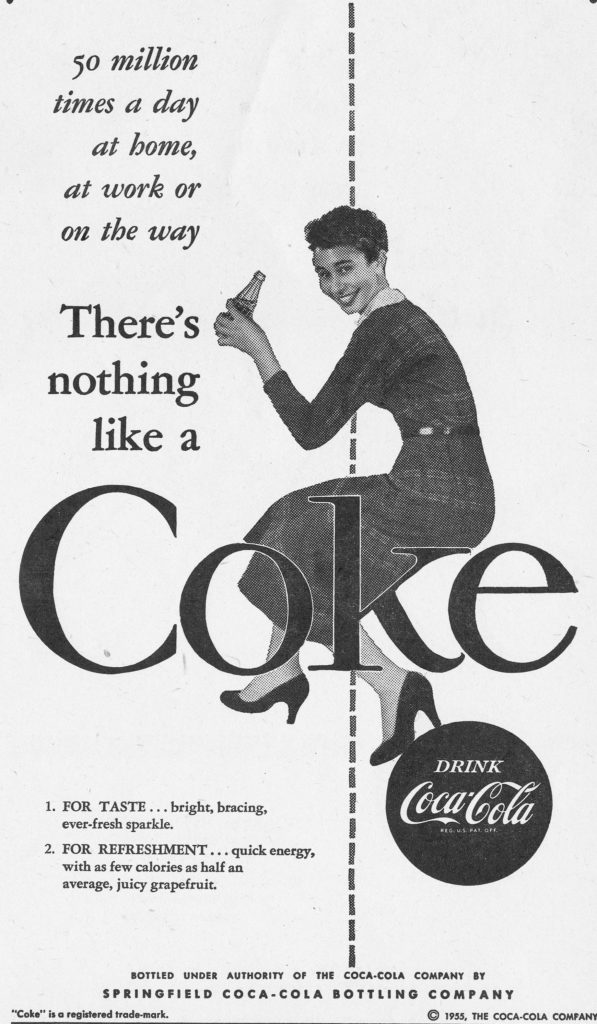

Mary Cowser Alexander, who was born May 25th, 1934, in Ballplay, Alabama, was never one of those girls who dreamed of modeling, popularity or profiles in magazines, but, in 1955, the Coca-Cola Company selected her to be the first Black woman to star in one of their iconic advertising campaigns.

Something About Mary

A soft-spoken, quick-witted, self-described “country girl,” Alexander began making history when she stepped onto Clark College’s campus in Atlanta. She and her sister were the first from her small town to attend college. Mrs. Cowser, Mary’s mother, instilled the importance of higher education in all of her children and sustained the strongest influence on Alexander’s life.

“She was a role model in the community as well as for the family,” Alexander explains. “She had a sixth grade education, but was a wonderful homemaker for 10 children and one wonderful husband.”

Mary undoubtedly made her mother proud. At Clark, she earned recognition when she was named to the Who’s Who Among Students in American Universities and Colleges, worked in the dormitory throughout the week and babysat for her college advisor and typing teacher, Dr. Hale, whom she “loved to death.” Whenever Dr. Hale ran late for classes, she would ask young Mary to open the classroom doors and get the students started on “thus and so.” Alexander truly enjoyed helping. She liked teaching but once considered majoring in something else until Dr. Hale said she could not. Alexander explains, “She was almost like my mama.”

And while Alexander focused on her future career, admiring eyes were on her. Alexander admits her popularity. “Before I started modeling for Coca-Cola, I was an attendant to the college queen.” That same year her dormitory matron told her that Coca-Cola was “looking for people to advertise and model for us,” adding, “I want you to go downstairs and apply.”

And while Alexander focused on her future career, admiring eyes were on her. Alexander admits her popularity. “Before I started modeling for Coca-Cola, I was an attendant to the college queen.” That same year her dormitory matron told her that Coca-Cola was “looking for people to advertise and model for us,” adding, “I want you to go downstairs and apply.”

Alexander dismissed the notion because she was already swamped. But her matron insisted. She says she never expected to be chosen from among the 75 girls representing cities such as Atlanta and New York.

Fear gripped her. “I wasn’t afraid to do it [modeling].” She says her butterflies stemmed from gaining her parents’ approval. “Back then, you couldn’t pick up a phone and have a talk with your parents.” Alexander had to write a letter and wait a week to 10 days for permission. Ballplay lay 15 minutes away from the nearest town and Mrs. Cowser had to walk 3 miles to the mailbox.

When Alexander did get a response, the answer was, “You can do it. But be careful.” Her father worried about the kind of posing she would do and he did not want any swimsuit modeling—a requirement for one of the ads. “My father was especially old-fashioned.”

But after Mr. Cowser saw the first check, he said, “OK.” The $600 payment was more than he made for months of farming. Mr. Cowser also became a fan of the product, which he had never tasted prior to Alexander’s modeling.

The then-college junior produced 14 ads for the soft drink giant, which meant she had to be present for photo shoots on three different settings, scheduled on weekends and holidays. Alexander recalls having to ride the bus to Atlanta from Alabama while on spring vacation and holidays; she couldn’t go straight home with her family members. She had to take a bus to Alabama alone.

In one ad, she sits at a piano. But it was only a prop. Her mother wanted her to take lessons from her sister, but Alexander confesses, with a laugh, that her sister was “not a good teacher.”

Eventually, she would hear of her image featured on billboards in New York and down in Mississippi. She unfortunately never saw any of those, but she did see herself in Ebony magazine.

“I was just thrilled,” she recalls with lingering excitement in her velvety voice.

Her favorite ad is the one of her seated behind a microphone.

In those days, she became somewhat of an archetype. After being selected to represent Coca-Cola, she became the college queen—a title bestowed by Clark’s football team. Alexander says coyly, “I was just blown away. I knew very little about football then.”

She was also unaware of her future influence. “Being 21, it never crossed my mind. I thought I was just doing something,” she admits. “If you were in a position to do this, that’s just normal for you to do that. I guess that is what youth will do for you.”

The ads were just a glimmer of the achievements that lay ahead for her.

A Can-Do Woman

Alexander maintained her determination and confidence as she advanced in her career. And while she didn’t let her Coca-Cola fame go to her head, she applied the fruits of her success wisely, using the proceeds from her modeling sessions to pay off her college education, something her mother felt was a requirement before marriage.

And although she had the looks, she never thirsted for the spotlight. She remained focused on becoming an educator. “I wanted to use my degree.” Unfortunately, teaching was not her first professional job.

And although she had the looks, she never thirsted for the spotlight. She remained focused on becoming an educator. “I wanted to use my degree.” Unfortunately, teaching was not her first professional job.

As a result of a discriminatory Detroit school system, Alexander worked as a real estate secretary for two years. She admits voicing her disdain publicly when a white woman with an associate’s degree received the teaching position instead. Alexander told the principal, “I know why you’re not hiring me. Because I’m Black, and she’s white.”

It took two years before that principal called her in for another interview and, in 1959, Alexander accepted the position and became the first Black teacher in Mount Clemens, Michigan. She became the head of the Business Education department, she is proud to share—a department that was composed “of all white teachers.” Later, she shattered the ceiling as the first female and first Black principal in the School District of the City of Highland Park. When her peers believed that women could not lead because they did not know enough about industrial education, Alexander replied, “Do the men know anything about home economics?” Her proficiency and confidence opened doors to serve in several leadership capacities: the State of Michigan’s first African American Vocational Education Director, the first African American on the Vocational Advisory Committee and the chairperson of that committee.

“They just used my little Black face everywhere,” she teases about the promotion of her many achievements.

Finally, in 1989, after 32 years of teaching and trailblazing for other Blacks and her fellow women, she retired and took on the role of directing a foundation for Buffalo Bills standout Reggie McKenzie. But she never strayed far from instruction, instituting tutoring services in Detroit and Highland Park and partnering with organizations like the United Way and the Chamber of Commerce.

Welcome to Ocala

For years, Alexander and Henry, her husband of 39 years, would vacation in Florida’s southernmost cities. On one occasion in 1990, the couple was heading back to Michigan when Alexander spotted a billboard boasting designer handbags.

“I love to shop,” she explains, so she told her husband, “Let’s go see what those handbags are like.”

The two avid shoppers took a detour into Ocala, and while Alexander did not find any handbags to her liking, Henry suggested they look around. Alexander stops to reflect on the pretty horse farms she saw at the time, “I just loved the horse farms, ‘cause I’m a country girl.”

They were so impressed they spent the night at a hotel on the then two-lane State Road 200. The following morning they woke up and ate breakfast at Bill Knapp’s Restaurant. Before leaving, they purchased flower pots to take back to their garden and vowed to return. In September of 1993, they returned and officially made Ocala home.

Interestingly, it was while packing that Henry discovered a mysterious photograph. He asked his wife, “Mary, this is your picture?” She conceded, “Yeah,” and he said, “Oh, I didn’t know you modeled for Coca-Cola,” to which she replied, “Oh, you didn’t?” Then Alexander told Henry, “Just throw that away. We’re not going to move that to Florida.” And Henry said, “Oh yes, we are!” Alexander insisted, “We don’t need that old thing.” She laughs about dodging a costly mistake—the picture, valued at $3,000 in 2007—reopened a world she left behind.

Family and Rediscovery

Alexander relays those memories with humor and modesty. She says “being with family and friends, teaching and sharing the joys of life” are her favorite pastimes. Perhaps that is why her niece came from Atlanta for a visit in 2007 and brought along a friend named Sylvia Wright. While the two girls rummaged through Alexander’s photo albums, they happened across the same memorabilia Henry had discovered 14 years prior.

Wright asked “Aunt Mary” if she could take a picture. Alexander agreed, thinking little of it until she received a follow-up call from Coca-Cola. She chuckles when she shares, “Coke didn’t know what happened to me. They thought we were all dead.” So Alexander had to prove she was indeed alive and that she was Coca-Cola’s first Black model.

Wright asked “Aunt Mary” if she could take a picture. Alexander agreed, thinking little of it until she received a follow-up call from Coca-Cola. She chuckles when she shares, “Coke didn’t know what happened to me. They thought we were all dead.” So Alexander had to prove she was indeed alive and that she was Coca-Cola’s first Black model.

A letter dated January 24th, 1956, from Jessie J. Lewis, a Black man, and the public relations representative from Birmingham Coca-Cola Bottling Company, Inc., sufficed. In the letter, Lewis writes, “Dear Miss Cowser, it was indeed a pleasure to have met you during my recent visit to Atlanta…Now I am assured that the Coca-Cola company made a wise choice in selecting you to advertise Coke.” With that, Alexander was center stage again.

During the grand opening festivities at the World of Coca‑Cola at Pemberton Place in 2007, Alexander, joined by 20 family members from all over the country, was celebrated for opening the door for others. She reminisces on Steve Harvey’s words to the audience, “Steve said many of us might not have made it to do advertising with Coca-Cola if it had not been for this lady right here.”

Alexander welcomes renewed interest from the media about her story as another opportunity to shed light on the value of diversity and inclusion.

Jamal Booker of the Coca-Cola Company says those considerations “are at the heart of our values and play an important part in our company’s success. In 1955, The Coca-Cola Company selected Mrs. Mary Alexander to be the first African American woman in Coca-Cola advertising. She has been an inspiring trailblazer throughout her life and we are honored that she plays an important and iconic role in the history of Coca-Cola.”

Local Interests and Loves

Alexander continued breaking down barriers after relocating to Ocala. The Alexanders played a part in integrating Our Redeemer Lutheran Church in 1993, where Mary started a tutoring program on Saturdays for children. Her tutelage lasted two years—up until a hip surgery prohibited her involvement. Still, she participated on various church committees and taught adult education for GED candidates at the nonprofit MAD DADS.

Besides her passion for education, Alexander lights up when she talks about flowers. As a child, she enjoyed digging up the front yard and planting rose bushes with her sister.

Besides her passion for education, Alexander lights up when she talks about flowers. As a child, she enjoyed digging up the front yard and planting rose bushes with her sister.

“At one time when I lived in Detroit, I had over 65 different rose bushes in my rose bed, as well as vegetables,” she recalls. Henry still gives her flowers on Valentine’s Day, and she will likely have more to enjoy as Mrs. Alexander turns 87 this month.

Diagnosed with scleroderma, an illness that affects her breathing and physical endurance, Alexander leaves her love of cooking to Henry, with no complaints. She says, “He’s a good cook.”

Education, gardening, cooking and entertaining family and friends are all mainstays. And what does she drink with all that she adores? Alexander has a favorite Coca-Cola product. She says, “I like that Cherry Coke.”

Legacy

Much like the women who spoke into her life, Alexander passes down wisdom like a smooth, refreshing swallow of a favorite beverage. She tells young people, “If the opportunity presents itself, that is the time for you to step forward and say, ‘Yes, I can do this. Just give me this opportunity.’” At family reunions, she imparts life lessons to the younger generation, teaching them where they have come from and where they are going.

Since Alexander’s graduation from Clark, nearly every high school graduate in Ballplay has gone to college. Doctors, lawyers, judges and heads of colleges now follow in her progressive footsteps.

So what’s next for Alexander? In her words: “If my legacy started on a farm in Ballplay, Alabama and allowed me to be a groundbreaker for other women and women of color, then I have done my job. If my legacy has been connecting young people with not only continued education but careers that will sustain their lives through retirement, then I have done my job. I will enjoy my flowers while I live through the grace of God.”