While many of us head to our air-conditioned offices each day, others put in long hours under less-than-ideal working conditions. These professions may not be glamorous or high profile, but they’re essential. Ocala Style takes an inside look at five of…

‘Good Old-Fashioned Elbow Grease’

At Ocala Recycling, ‘going green’ often means getting dirty.

Ocala Recycling’s shredder facility is quite a site to see—and hear. The low rumbling of heavy machinery grows louder as an abandoned automobile or appliance is dropped into the massive shredder. The sound emanates through your feet and up into your chest. Ten 200-pound steel hammers break down the metal like a flimsy soup can, reducing what was once a 2,000-pound item to a pile of dirty rubble.

Once the items are shredded, they are sent via conveyor belt to the cyclone, where they are blown with air at a rate of 200 cubic feet per minute to rid the pieces of excess dust and debris, or “fluff” as it’s known in the business. A 150-horsepower engine runs the machine.

“Consider the cyclone a big vacuum system that blows and sucks debris off the shredded material,” says Ferrous Manager Billy Warbach.

Several times a day, a piece of rebar or a leaf spring from an automobile suspension gets caught in the cyclone, stalling the shredder. When that happens, someone has to physically climb into the machine to locate and release the jam. It’s not a pleasant job.

Darrel Gunter (left) and Jon Coots take a moment out of their work day at Ocala Recycling.

“It smells like an old, wet pile of clothes that’s been left out in the heat,” says Billy. “It’s dark and humid in there. The metal-on-metal friction of the shredder really builds up the heat within the system. We add water to reduce that heat, which produces excess moisture and humidity.”

A sorter at Ocala Recycling, Joseph DeRiso often finds himself climbing the 40 feet to the top of the cyclone to clean out trapped debris. The machine is shut down to ensure his safety isn’t compromised. Flashlight in hand, Joseph enters what’s known as the Z-Box through one of two small hatch doors, physically climbing into the machine.

“Depending on how bad the clog is, sometimes I’m able to just kick it free,” he explains. “If the jam is bad, I may have to use a poker or even a blow torch to free up the machine.”

As the blow torch sparks fly, the Z-Box’s dirty walls are illuminated, revealing a thick, damp coating of powdered metal you can almost taste, like chewing on aluminum foil or placing a coin on your tongue.

When Joseph emerges from the box, his forehead is fraught with beads of sweat, his uniform is covered in black soot, and the outline of his safety goggles is clearly visible on his face.

A crane prepares to pick up a discarded automobile at Ocala Recycling.

Ocala Recycling Co-Owner Michael Bianculli calls it “good old-fashioned elbow grease.”

“The first thing I do when I get home at night is take a shower,” Joseph jokes. “My wife wouldn’t have it any other way.”

‘Like A Big, Dirty Shop-Vac’

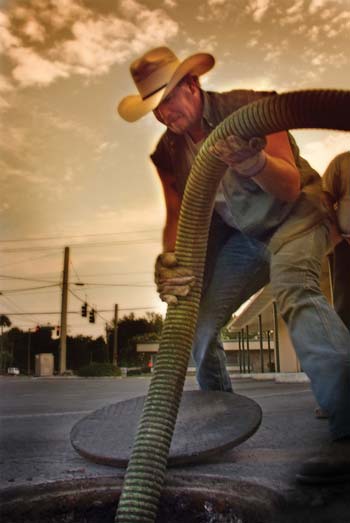

Brown’s Septic Tank Service takes care of what’s left behind.

The 65-degree temperature and gusty winds weren’t enough to disguise the stench that emanated from the opened grease trap outside of Ocala Regional Medical Center. Standing upwind didn’t seem to help, either. It’s enough to make you hold your breath.

“It smells worse when the manhole cover is first opened,” says Lee, a driver and pumper for Brown’s Septic Tank Service. “When the lid is sealed, the gasses are contained within the tank. Once the lid is popped, all of those gasses and smells are released into the air.”

“Grease smells the worse,” adds Vice President Chad Ankney. With 200 beds and an average of 138 patients to care for on a daily basis, the hospital’s six septic tanks—7,200 total gallons—are pumped on a weekly basis.

Lee, a driver and pumper with Brown’s Septic Tank Service, lowers a hose into an opened septic tank to retrieve its contents.

As Lee pops the valve on the back of the truck, a gush of brownish, foul-smelling liquid escapes into a waiting bucket.

More than 200 feet of thick, heavy hose is wrapped around the 3,600 gallon pump truck. Lee unwraps the hose and drops it into the murky liquid filling the tank. The truck draws the tank’s contents out at 19 pounds per square inch. As the liquid is pulled from the tank, the hose jumps and sputters when air is sucked through the system. The truck’s contents are noted in four large glass bubbles as the brown liquid swirls through the glass, indicating how full the truck is.

“It’s like a big, dirty Shop-Vac,” says Lee. “How long the job takes depends on the amount of solids at the bottom of the tank.”

While liquid will easily pass through the system, foods such as noodles, rice, and grease stick together, creating a thick substance at the base of the tank.

“The rotting, decomposing food smells worse than any septic system you could find,” says Chad. “It’s especially challenging when the system hasn’t been properly maintained.”

Lee agrees.

“I had a job where the system was 20 years old and never pumped,” he says. “The contents were a solid brick. I first had to get enough liquid into the truck to be able to backwash it and send it back to the tank to loosen it up. It was pretty nasty and took almost three hours.”

For Lee, the hose is the dirtiest part of the job.

“I’ve ended up with the contents of the tank on my chest and clothes,” he says. “It’s not pleasant.”

Exterminator Tom Peek of A2Z Pest Control crawls out from under an Ocala house after an inspection.

Once the truck is full, Lee heaves the heavy hose out of the tank and seals the valve on the truck. The tank’s contents are transferred to Brown’s treatment facility.

The tank is dumped into a large rotating filter that separates the liquid from the solids. The liquids pass to the holding tank where they are aerated and treated with lime to improve the pH level and kill the bacteria.

“Once the proper pH level is sustained, the pump truck comes back and pulls the liquid from the tank,” says Chad. “It’s used as field fertilizer at places like golf courses. I always cringe when my friends put their used golf tees in their mouth.”

The decomposing food and trash that stayed behind at the screener is dropped onto a stainless steel stay and allowed to dry before being hauled to a dumpster. Chad describes the stench as “rancid.”

Lee adds that while some jobs are easy, others are quite the opposite.

Lift station cleaning requires a hose, a collection truck, and lots of suction power, all manned by Ocala Water & Sewer employees.

“Some of the hardest are the residential tanks that are buried,” he says. “I have to physically search for the tank and dig it out with a shovel, which is especially difficult on 100-degree days. It also gets dirty when the tank covers are broken. When that happens, I have to put on my rubber boots and get into the tank to pull out the solids. Those aren’t the best days.”

‘A Very Tight Workspace’

At A2Z Pest Control, workers get up close and personal with nature.

The crawl space is only 24 by 15 inches, but Tom Peek of A2Z Pest Control is unfazed, even eager. He’s after one formidable, albeit very small, enemy. On comes the hazmat suit and gas mask, and with flashlight in hand, he slips head-first on his back through the rectangular hole, using his legs to slide further and further under the house. A short time later, he emerges, head-first and still horizontal, with a short piece of wood in his hand.

“Termites,” he nods, as he hops to his feet. “Subterraneans. Southeastern subs.”

One thing is immediately clear: Tom, or Dr. Death as the exterminator’s commonly known, loves his job.

The house will be chemically treated with Termidor. Tom digs a trench around its perimeter, treating the soil with the termiticide, and then backfills it, creating an invisible barrier against the insect. If the house is not on a concrete slab, he repeats the process underneath the house, which is usually a very tight workspace.

Having Southeastern subterranean termites is comparatively good news for an Ocala homeowner, if one had to choose a termite to have. Easier to spot and treatable by trenching, Southeastern termites are preferable to the dry-wood variety, which requires fumigation to eradicate, or the much-feared Formosan species. The mere mention of the latter’s name halts Tom mid-conversation.

“The Formosan,” he pauses, shaking his head. “They are the baddest of the bad, the great white shark of termites.”

He’s fought them. Once. The only exterminator in Marion County to have done so.

“The Southeastern subs have about three-quarters of a million in their colony. The Formosan have 7.5 million,” Tom explains. “They have five times as many soldiers, and they’re very aggressive. The soldiers make sure everybody is doing their job. If one isn’t, they kill it. Just bite it in half.”

A former North Marion Middle School science teacher, Tom, not surprisingly, was one of those kids growing up who loved having insects and snakes as pets. He still does. What makes most people’s skin crawl fascinates Dr. Death. Although he loves a good termite fight, Tom also takes on a laundry-list of other pests: ants, roaches, fleas, scorpions, ticks, moths, grasshoppers, spiders, rats, snakes, possums, and skunks, to name a few.

Tom works shoulder-to-shoulder with his employees, and some have been with him for decades. So, just how does one keep employees motivated when they’re fogging roaches or trapping rats?

It’s very simple, Tom says: “I never ask them to do something I wouldn’t do myself.”

‘Down-Right Nasty Work’

Keeping Ocala’s pipes clean is a never-ending job for Ocala Water & Sewer employees.

Most people don’t think twice about what happens after they shut off a faucet or flush a toilet, and they’re probably just as content never to think about it. But Jeff Halcomb does. So do Tim Maynard and Kenny Shuman. As City of Ocala Water & Sewer employees, their job is to keep our city’s pipes clean, and part of that responsibility includes maintaining the city’s 123 lift stations.

On an average summer day in Ocala, the temperature on a roof can easily exceed 120 degrees while Scott Smith roofers work.

Even if you can get past the stinging smell, the frequent rats, and the occasional syringe, the biggest hurdle to overcome in lift-station cleaning is the small, simple fact that it’s lift-station cleaning. For Ocala homes on city sewage, water (from sinks, dishwashers, washing machines, and yes, toilets) flows out of the house through a series of pipes that lead to a lift station. There, pumps raise the incoming waste water to the necessary level for gravity to take over again, causing the water to flow to the next lift station or to the waste water plant.

However, not all of the incoming material gets out, settling instead like sediment at the bottom of what’s called the wet well. Left unattended, the well can clog. If that happens, the unmanaged station would smell far worse than it already does and, of course, would not work properly.

Workers remove the accumulated sludge with a hose, a collection truck, and a massive amount of suction power, not unlike a giant Shop-Vac. In a non-submerged lift station, the incoming waste flow is held at bay as a handful of workers in hazmat suits, gloves, and surgical masks climb down the well’s staircase to work the suction end of the heavy hose while another stands at the staircase’s top—for better leverage—to help guide it with a rope. A water gun, capable of administering 3,000psi of pressure, is also used to break up the solidified waste. Additional workers hold the hose in their hands to control the sudden jerks as waste passes through.

The smell that is so pungent at first, but grows surprisingly bearable, is caused by hydrogen sulfide gas, which is also toxic. While odor-control mechanisms keep hydrogen sulfide levels low, workers must still take a small monitor inside the well to check oxygen levels. They also wear headphones to muffle the deafening suction noise. Lift stations are inescapably hot, especially for those wearing the Tyvek protective suits, but with more than 100 such stations to maintain, the workers can’t afford to clean only during the agreeable months. They work through every season and without much recognition for the public service they perform.

“These guys are happy to stay behind the scenes,” explains Jeff Halcomb, deputy director of operations for the City of Ocala Water & Sewer. “Yes, it’s down-right nasty work, but they’re just doing their job.”

‘A Different Kind Of Tired’

For Scott Smith roofers, long days and sweltering heat come with the territory.

The numbers alone speak volumes about the grueling work of roofing. On a 95-degree summer day in Ocala, a roof’s surface temperature can reach 120, even 130 degrees. Eight out of every 10 trainees hired by Scott Smith Roofing can’t handle the work and quit within the first three days. Most don’t even last that long. For those who can cut it, the day starts at 6:30am and ends around 6:00pm.

“Our job is very tough, particularly because of the elements,” says Wayne Smith, president of Scott Smith Roofing. “It ranges from freezing cold in the winter to 95 degrees during the summer. And it’s physical, hands-on work. It’s abusive.”

Looking up and watching roofers nail shingles, it’s easy to think they’re not that high up. But like most things, perspective is everything, especially when you’re standing on a steeply pitched roof with a pneumatic nail gun in hand.

Looking down is much more daunting than looking up, even on a single-story structure. Roofers become perfectly at ease with the height, and over time, their muscles grow accustomed to standing at severe angles and hunching over to nail shingles, says Wayne, who spent many a day on a rooftop himself.

Surprisingly, the roofers forgo tread-heavy shoes for the more flat-soled, flexible kind. If the building is several stories high or the pitch is extreme, the workers will wear a harness. Above all else though, cleanliness is key to safety.

“Keeping a clean job is very important,” explains Scott Smith Jr., vice president of the Ocala company. “We sweep up the loose granules and nails because roofers can slip on them. But, ultimately, you’ve just got to be able to do the heights.”

Residential re-roofing begins with the dirty job of shingle tear-off. Leaks and other problems are dealt with after the crew—usually three or four roofers—have removed the underlying tar and can see the bare plywood. After the roof has been examined and repaired, the crew rolls out a new layer of tar paper and begins the laborious process of layering and nailing new shingles. Aside for the hiss of the nail guns and the low music emanating from a nearby radio, the job site is quiet with the roofers working quickly and efficiently. A re-roofing takes about four days, and when the work is done, the roofers simply pack up their tools and head off to the next rooftop.

“It’s a different kind of tired after being up there all day,” Wayne says, “but it’s very gratifying work.”