On the wall in Steve Saint’s Dunnellon office hangs a striking photo of an Ecuadorean man in tribal dress. The warmth and kindness in the image is palpable—a smile creases his face and extends to a pair of strikingly dark eyes. For decades, Steve has known Mincaye as “Grandfather,” despite one disturbing fact that would tear most families apart. This is the man who killed Steve’s father.

Born to missionary parents in the jungles of Ecuador, Steve was just five years old in 1956 when his father, Nate Saint, and four other missionaries were speared to death by a group of Waodani. A notoriously violent tribe, the Waodani were known to kill any outsider who penetrated their territory. Yet the missionaries had made peaceful contact just two days earlier and were hoping for another promising interaction. Instead, they were ambushed and killed, their bodies left floating in the river, their plane destroyed.

Steve faintly remembers watching his father’s yellow Piper Cruiser fly away that day. But what is seared in his memory is what happened afterward.

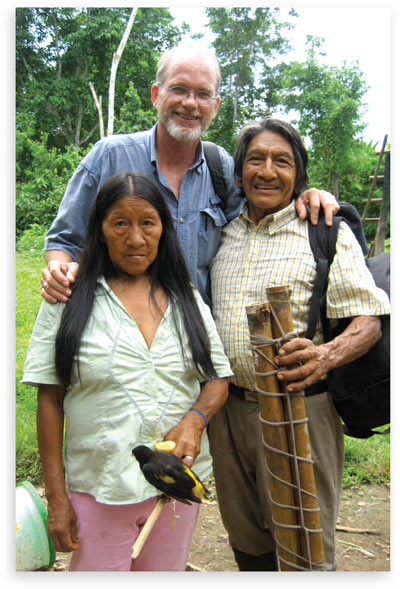

Steve Saint, who is a longtime pilot (top), has dedicated years of his life helping and studying Ecuador’s Waodani tribe (above).

“One of the most vivid memories wasn’t the day he left, but the days that he didn’t come back,” recalls Steve.

Seeing his mother, Marj, and Aunt Rachel (Nate’s sister) in tears, young Steve knew something was very wrong. But what he couldn’t imagine then was how his own life would be forever altered by the deaths of his father and the other missionaries.

At the time, Shell Oil was in Ecuador—a country roughly the size of Colorado—exploring for oil. The Waodani had already killed several Shell employees so the fact that tribal members had killed the five missionaries was not surprising. But what happened next was.

Steve holds a photo of the man he calls grandfather, Mincaye, an elder in the Waodani tribe.

Despite the circumstances, Marj and Aunt Rachel didn’t flee the jungle and return to the States. They stayed, cautiously continuing to reach out to the very people who had killed their family member. Amazingly, Aunt Rachel and one of the other widows, Elizabeth Elliot, even moved to Waodani territory to live among the tribe.

Before the tribe became “God followers,” as they now describe themselves, they were classified as the most violent society ever studied by anthropologists. Homicide rates within the tribe itself were a shocking 60 percent. As Dabo, one of the tribe’s most noted warriors said of the missionaries and their attempts at religious conversion, “If these people had not come with this new information, there would be none of us left.”

Even with the dangers, Steve joined Aunt Rachel in the jungle, living there off and on between the ages of 8 and 18. Raised “tribal,” as he puts it, his adopted Waodani family taught him to hunt, read trails, stalk game, and hunt monkeys with blowguns and poison darts. At age 13, he was baptized in the same river where his father perished, by two of the same men who had manned the spears that took his father’s life.

Looking back, Steve sees that fateful day of his father’s death not as chaos, but as divine order.

“I’ve listened to the Waodani tell hundreds of killing stories, but I’ve never heard of them attempt to kill someone unless they had superior numbers and the opportunity of surprise. The likelihood of those six warriors attacking five foreigners who had guns and an airplane was preposterous,” he recalls. “I think God planned it.”

In 1973, Steve met Ginny Olson, a young woman from Minnesota who was traveling with a singing group in Ecuador. He served as the group’s jungle trail guide, and after just three days he was smitten. After Ginny left for home, he flew to Minnesota, met her parents, and convinced her to return to Ecuador. The two married three months later. Four children (their youngest daughter died of a brain aneurysm in 2000) and 16 grandchildren later, their marriage still thrives today.

Steve, his wife, Ginny (fifth from the left), and their family visit the Waodani.

“We’ve been married 37 years,” Steve says with a smile, “and they have been really, really good years.”

At the age of 23, Steve left Ecuador to make his life in the U.S. He still maintains dual citizenship. A graduate of Wheaton College, he launched several successful businesses and also served as a missionary in Africa. He and Ginny have lived in Marion County since the early 1980s and raised their family here.

In November 1994, after 20 years in the States, Steve returned to the jungle after Aunt Rachel passed away. Although she had flown to Ocala for cancer surgery, it was her wish to return to the Waodani to live out her final days.

Following her funeral, Mincaye and other tribal elders said something that once again changed Steve’s life.

Steve with Mincaye and his wife during a trip to Ecuador

“They said I needed to come back and live with them again so I could teach them,” he recalls. “One of the problems around the world has been that foreigners go into an area to reach people and do things for them, but never teach those people how to do the same things for themselves. The indigenous people end up thinking they must rely on outside help.”

Still, Steve faced an agonizing decision.

“I’d spent 20 years doing business in North America. I had a wife and four children,” he says. “I couldn’t imagine any practicality in this and I made excuses as to why I couldn’t go.”

It didn’t take long for Steve to stop making excuses, though. He, Ginny, and their children left Florida behind and moved to the Ecuadorean jungle to live among the Waodani from early 1995 through August 1996.

When he returned to the States, he immediately began developing the non-profit organization known as Indigenous People’s Technology and Education Center, which was built around the concept of teaching a man to fish, rather than just giving him a fish (see sidebar). I-TEC’s offices are currently located at the Dunnellon/Marion County Airport.

“Just because people are low-tech doesn’t mean they are low IQ,” says Steve. “It’s not possible to teach them to be like us, so we have to change technology to fit the Waodani and people like them.”

“We’ve sent out over 360 I-Dent [dental] systems so far,” says Mark Stringer who has served as I-TEC’s dental equipment coordinator since 2007. “The philosophy of being able to ‘teach a man to fish’ is the best thing to do. It’s the reason we’re here.”

The offices at I-TEC are filled with computers and the latest technology, yet primitive spears, nine-foot-long blowguns, handmade hammocks, and other tribal items are displayed in every room. Steve, who speaks five languages, is still more than capable with a blowgun himself.

“Missionaries have gone to many of these remote locations, and the indigenous believers are grateful, but they also want to learn something practical so they can reach their own people,” remarks family friend Steve Buer. “Steve has more energy than I’ve seen in anybody. His mind is always working.”

In addition to putting in long days at I-TEC, Steve Saint travels frequently, often with Mincaye. The men have spoken to groups around the world and have appeared on radio and television shows. Half a century after the deaths of Steve’s father and friends, their story continues to inspire.

“Many years later, my mom told me that when my dad and his friends were killed, she received nasty letters. People were angry with us because they thought this would discourage other people from being missionaries,” recalls Steve. “But I’ve had thousands of people come to me over the last 50-plus years saying how deeply impacted they’ve been by what happened to my father and his friends, that it really motivated them to reach out.”

Want To Learn More?

itecusa.org

(352) 465-4545

Read more about Steve’s story in his fascinating book End of the Spear, which was also made into a major motion picture of the same name in 2006.

Courtesy of EthnoGraphic Media.

I-TEC develops numerous products—both hi-tech and lo-tech—to help those in need.

I-Dent: Allows indigenous people to train with a professional dentist. Steve and his crew invented a Portable Dental System complete with a dental chair, instrument tray, and battery-powered dental accessories, all of which fits into a 34-pound backpack.

The I-Dent (above) is aportable dental chair that can fold up to fit inside a backpack. Photo by John Jernigan

I-See: A program that teaches the basics of vision care and provides new glasses, allowing an indigenous business ministry to administer check-ups and fittings.

I-Fix: Teaches indigenous people how to maintain and repair small engines, helping extend the life of chainsaws, tractors, and motorboats used for work and transportation.

I-Med: An intensive medical training program still in the developmental stages. The non-verbal training DVDs will teach basic healthcare services, including lifesaving techniques, anatomy, hygiene, and medicine delivery.

The Maverick: A flying car that won the Breakthrough Award from Popular Mechanics in 2009 that uses regular gas, not aviation fuel, and barely needs 100 feet of open space to take off. The fabric wings fold neatly into a compartment in the roof, but when they are not expanded, the entire contraption resembles a sporty off-road vehicle. On the highway, it travels as fast as other cars, but in the air, it travels along at a moderate 40 miles per hour. “If you can drive an automatic transmission car,” says Steve, “you can drive this.”

Steve Saint with his award-winning flying car, The Maverick. Photo by John Jernigan