During these incredibly challenging times, as we grapple with America’s current and unfolding national race crisis, we look back on the legacy of school integration here in Marion County as told by those who experienced it firsthand.

Equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world,” reads the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), which was drafted by representatives from different legal and cultural backgrounds, from all regions of the world, and issued by the United Nations General Assembly in Paris on December 10th, 1948. “Whereas disregard and contempt for human rights have resulted in barbarous acts which have outraged the conscience of mankind, and the advent of a world in which human beings shall enjoy freedom of speech and belief and freedom from fear and want has been proclaimed as the highest aspiration of the common people,” it goes on to say. “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.”

The declaration is a milestone document in the history of human rights that has been translated into more than 500 languages. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt played a pivotal role in drafting the declaration and lobbied governments around the world in order to unite them to adopt this common standard. It was the first time that a global expression of fundamental human rights, to which all individuals should inherently be entitled, had been set forth.

“Human rights include the right to life and liberty, freedom from slavery and torture, freedom of opinion and expression, the right to work and education, and many more. Everyone is entitled to these rights, without discrimination,” it states. And it goes on to say, “Everyone has the right to education. Education shall be directed to the full development of the human personality and to the strengthening of respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms.”

“Human rights include the right to life and liberty, freedom from slavery and torture, freedom of opinion and expression, the right to work and education, and many more. Everyone is entitled to these rights, without discrimination,” it states. And it goes on to say, “Everyone has the right to education. Education shall be directed to the full development of the human personality and to the strengthening of respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms.”

Following the abolition of slavery in the United States, blacks were separated from whites by law and

through private action in all modes of transportation, public accommodations, the armed forces, recreational facilities, prisons and schools, in both northern and southern states. Though the constitutionality of racial segregation was challenged by those brave enough to confront the system, a U.S. Supreme Court decision in the case of Plessy v. Ferguson, handed down in 1896, ruled that states could allow racial segregation, as long as the facilities were “separate but equal.” However, facilities and opportunities for black children in segregated schools were not at all equal and typically were vastly inferior. In most southern states, schools were almost exclusively segregated.

In the 1930s, it was the lawyers of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) who strategized to bring local lawsuits to court, arguing that separate was not equal and that every child, regardless of race, deserved a first-class education.

One of the key goals of the Civil Rights Movement was the effort to desegregate public schools throughout the United States. The lawsuits begun by the NAACP were combined into the landmark U.S. Supreme Court case Brown v. Board of Education, in which the justices ruled unanimously that racial segregation of children in public schools was unconstitutional, thereby outlawing segregation in schools in 1954.

The verdict did not specify how schools should be integrated, however, so it was not universally enforced until the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The act was aimed at removing racial roadblocks, ending Jim Crow laws and eliminating school segregation. It was intended to provide equal access to restaurants, transportation and other public facilities as well as break down barriers in the workplace for blacks, women and other minorities. It was only then that the widespread process of desegregation would move forward with the backing and enforcement of the Justice Department and compel communities to integrate public schools.

Such was the case in Marion County, which chose to maintain a segregated school system until the county found itself under the threat of losing its federal financial assistance. For three years, Marion County “desegregated” schools through the “Freedom of Choice” or “Option Out” plan, which was an approach adopted by southern states that allowed a student to request to go to an integrated school, but was ultimately a way for school districts to continue to operate a racially dual (segregated) school system and placed the burden of desegregation on black students. This plan had a fairly negligible effect on segregation, as most students chose to attend their former schools.

A Brave Few

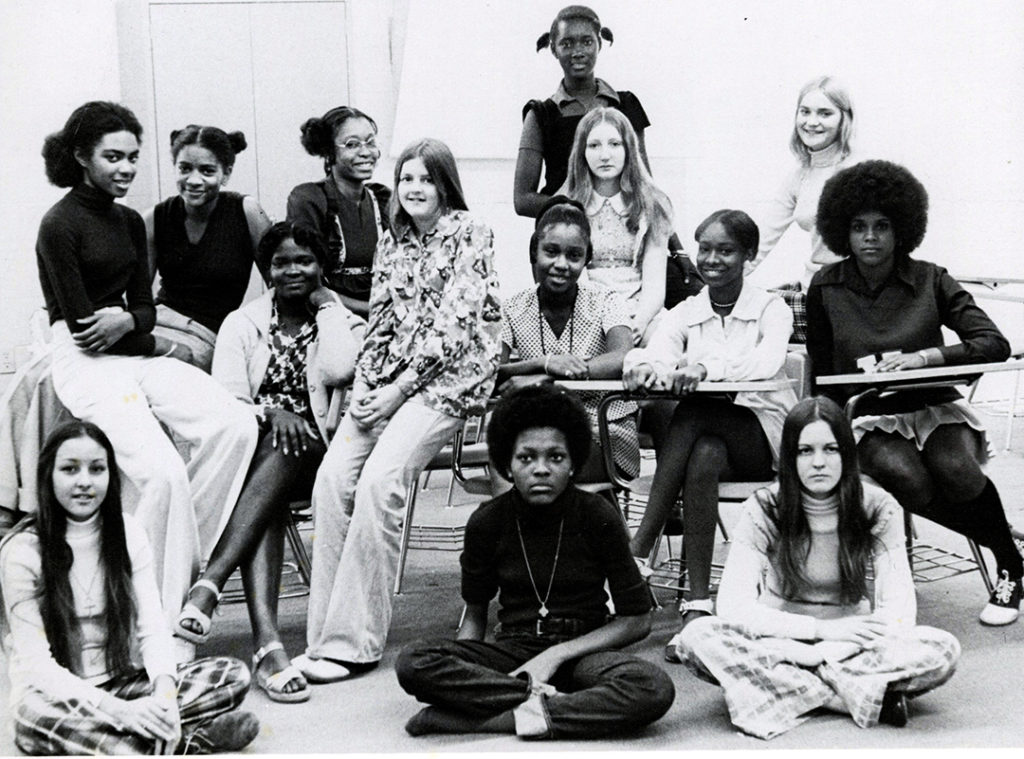

In September 1965, as they entered the 10th grade, 34 students left Howard High School, which had an all-black student body, and transferred to Ocala High School (OHS), a previously segregated school, under the “Freedom of Choice” plan.

These early pioneers of integration were among the black students who completed their sophomore, junior and senior years at the school and graduated from OHS in 1968—becoming a part of the school’s first integrated graduating class.

One of those students, Sylvia Jones, recalls the racial climate that existed in the community when she decided to move to OHS.

“When you would go downtown, there were two water fountains…‘White’ and ‘Colored.’ The bathrooms were ‘Men’, ‘Women’ and ‘Colored.’ If you were black, you were not allowed to sit at the counter at the corner drugstore. We always had to go to the back door at JCPenney, Sears…the Marion Hotel. We were tired of using the back door,” she declares. “We were ready. We were part of a movement and we were not afraid. Our parents were more afraid than we were.”

“When you would go downtown, there were two water fountains…‘White’ and ‘Colored.’ The bathrooms were ‘Men’, ‘Women’ and ‘Colored.’ If you were black, you were not allowed to sit at the counter at the corner drugstore. We always had to go to the back door at JCPenney, Sears…the Marion Hotel. We were tired of using the back door,” she declares. “We were ready. We were part of a movement and we were not afraid. Our parents were more afraid than we were.”

Jones explains that it was her grandparents who raised her and that because they were older than most of her fellow students’ parents, they had deep reservations about integration.

“My grandmother, Mary Vereen Jones, was a teacher with Marion County schools for 43 years. She was born in 1908 and daddy was born in 1898. That’s who I call Momma and Daddy,” she explains. “They were very concerned for us.”

She remembers that her grandfather even rode around the school parking lot with a shotgun during her the first few days, just in case of trouble.

“I did ninth grade at Howard,” Jones explains. “At the biology lab at Howard, we had one microscope. Every book we had was used and had an Ocala High sticker on it. They were all marked up inside. We had 30 algebra books and over 50 students. So when the bell rang, everyone would rush to try and check one out overnight. It was impossible, but that was what we had.”

Those educational disparities motivated her to elect to integrate and attend 10th through 12th grade at OHS.

“I was tired and I felt, I’m not getting what I need, what I deserve to have,” she recalls. “It was my own choice. It was something I had to do.”

Another of the students, Ron Coleman, whose family was also involved in the educational vocation, feels desegregation was not only an important part of the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, but that his desire for equality and a better education went into his making this decision.

“Growing up in a family of educators, it was emphasized that we would definitely go to college,” he offers. “It was also known in our family and the community as well that the quality of education on the ‘other side’ was far better than what we were receiving in our community. So, it was instilled in us at an early age that, despite the inequality, you will go ahead and achieve all you can achieve, given the resources available to you. I knew that when the opportunity came, I would be among the first to seize it and ‘cross the tracks’ to engage in a higher quality education.”

Coleman recounts that his mother, a teacher at Madison Street Elementary School in Ocala, saw a clear opportunity for a better education at OHS. Unfortunately, when he was just 15, she passed away, during the summer before he would integrate.

“My dad still had some reservations about it, but he knew it was the right thing to do,” Coleman asserts. “It made all the difference in the quality of the education we received.”

But he had something just as important as his education in mind when he made the choice.

“I had been a part of the Civil Rights Movement in Ocala as a teenager and I saw the integration of schools as a way to take it a step further,” he reveals. “I had been a part of the picketing, the boycotting and the sit-ins.”

Those same protests were fuel for Cheryl Lonon Walker, now a retired educator living in Tallahassee, to join the other students in OHS’ first integrated class.

“When I started out with the freedom marches, it gave me a kind of fearlessness that became a part of my attitude,” she remembers. “I didn’t fear being where I was or where we were going to school.”

Walker attributes that newfound fearlessness as the key to how she was able to forge relationships with white students early on.

“It wasn’t a conscious effort. The only agenda I had was that I wanted people to know me. I wanted to reach out to others and allow them to reach out to me. I felt that if I opened myself up, then other people would relax,” she admits. “That helped to break down walls and I was able to accept a closeness with people who were not just like me. It also helped break down walls for the white students. Those friendships allowed us to be ourselves and embrace the differences, as well as realize that we had a lot of similarities in our lives. We didn’t live in the same place, we had different churches that we attended, but we all had to eat and we all enjoyed the things that most young people enjoy,” she continues. “We found out that we were very alike with regard to some of the things we were going through with our parents. When you find out the ways in which somebody is like you, you can become a friend to that person. But you can’t find out those things if you don’t communicate.”

Walker credits her parents with helping her develop both openness and a sense of humility.

“My mom told me that if you want a friend, you have to be friendly. You have to show your friendliness. And if you meet someone who doesn’t have a smile, then give them yours,” she recalls. “My father gave me some words of wisdom about going to a predominantly all-white school. He said, ‘No one is better than you and you’re not better than anyone else.’ So, with those things in my heart and mind, I went into that situation believing that I was as good as anybody else. I never thought that I was less than anybody else.”

Walker says that many of her relationships formed during high school, with both her white and black friends, are still thriving today.

Walker says that many of her relationships formed during high school, with both her white and black friends, are still thriving today.

“We have been there, through the years, sharing experiences, supporting one another,” she shares. “Our faith has been a foundational element of our relationships. It has kept us together. If we are different in a lot of different ways, we sure can say that we are alike in that one fundamental way. We have faith in God and God is love. So, if he is love, then we have to love one another. That is what has kept us going, our faith, our fearlessness, learning about our differences and embracing our similarities. It broke down those barriers and created relationships that are long lasting.”

For Jones, who points out that there were no black teachers or administrators at OHS when the black students first arrived, it was her relationships with a caring guidance counselor named Ms. Full, who she explains had a way of understanding her, as well as a special teacher, Mrs. Ruth Marcos, that nurtured her during that vulnerable time of transition.

Jones praised Marcos for her “understanding and encouragement” in creative writing, and for demonstrating her belief in her by making her the editor of Satori, her senior year creative writing class book.

“It was a very, very nice experience, putting this together,” Jones offers with a laugh, flipping through the pages. “This takes me way back.”

Jacquelyn McKnight Rhone also benefited from close relationships with several teachers during her time at OHS.

“My ninth grade English teacher was true to who she was,” Rhone recalls. “It didn’t matter if you were black or white. She treated you kindly and didn’t put anyone down.”

She says she often remembers things that English teacher and her 12th grade humanities teacher imparted to the students in their classes. She felt lucky to be a part of the integration experience.

“I’m glad that I was in the position to be a part of it,” she proclaims. “It was something that was needed, because we were always told that the black schools got the same as the white schools. But we knew that wasn’t true. So, from a personal standpoint, it was great to have the opportunity to be able to have access to better everything,” she continues. “I was glad to be able to see the strides that were made from the time I was in junior high and we were protesting, to then see that it did have an effect and the results were positive. I knew that my child and grandchildren would have the opportunity to go to better schools. Because we did integrate and there were white students that had to go to predominantly black schools, then the standards came up for all schools. That was the positive impact of integration.”

Cultural Shift

But the road to integration was not a smooth one.

Coleman recalls that some of the white students accepted the incoming black students and some objectively did not. He also remembers there were rare cases of physical conflict.

Lena Hopkins-Smith, a native of Ocala and 1972 Vanguard High School graduate, was also part of the “Freedom of Choice” program in 1966 while in the sixth grade. She transferred to Fort King Junior High, beginning with the seventh grade.

Hopkins-Smith says black students “were culturally different and outnumbered.” They were not represented in student government or team activities, she shares. Black students tried to create solutions to these issues, she explains, but eventually they resorted to such protests as sit-ins and walkouts.

Hopkins-Smith says black students “were culturally different and outnumbered.” They were not represented in student government or team activities, she shares. Black students tried to create solutions to these issues, she explains, but eventually they resorted to such protests as sit-ins and walkouts.

Gail Smallwood Capshaw, a fourth-generation Floridian, who now lives in Las Vegas, was among the white students who were caught in the culture clash of Old South attitudes and the whole new world of integration.

“I had great compassion for those students, because I knew how hard it would be for me if they put me on a bus and took me over to Howard High School. I couldn’t have imagined what that would have been like,” she reveals. “It was a time of a lot of confusion. It was so hard and disruptive, but I realized it had to be…it needed to be.”

In trying to navigate the cultural shift, Capshaw found herself pushed to her limits.

“I can tell you a story…” she begins, before breaking into tears. “I’m sorry…I get choked up still to this day,” she continues. “We had chemistry class right after lunch and some of the [white] boys would go into the classroom and turn the desks of these three black girls upside down. And these girls would have to come in and turn their desks right side up. It was humiliating,” she says with a tremble in her voice. “I don’t remember thinking about it, and it was not really my personality looking back on it, but I remember one day I said to the girls, ‘No, I am going to turn the desks back up,’ and I did. Then I went to the guys and I said, ‘Don’t you ever do that again!’ and to my knowledge they never did.”

Capshaw admits that her upbringing hadn’t really prepared her for the changes brought about by the Civil Rights Movement.

“I just watched The Help last night with my 13-year old granddaughter,” she shares. “I wanted to give her some idea of how things were, because I lived it.”

She also wanted to give her granddaughter a historic perspective of how that period in our history relates to what is going on in our country today.

She explains that her mother had a black maid, while she was growing up, who helped prepare meals, especially around the holidays. She recounts a painful lesson she learned pre-integration.

“It was Thanksgiving Day and the table is all set and the family is gathered around and I saw Bessie Mae in the kitchen, on a stool,” she recalls of their maid. “So, I asked my mom, ‘Why isn’t Bessie Mae sitting with us?’ You know they would laugh and joke, they were like best buddies…until we sat down to eat the meal. And she said, ‘Gail, keep quiet. Do not say that!’ and I nearly got a spanking for asking. So, I learned not to say a word and that was what was ingrained—keep quiet. We have the benefit of hindsight now, but it was confusing as a child. They were hard times, but we just tried to do the best we could.”

The Next Phase

On February 1st of 1968, the Department of Health, Education and Welfare (HEW) notified Marion County of the probable noncompliance of the school system with regard to the requirements under the Civil Rights Act and threatened the termination of federal educational funds if Marion County did not comply with HEW’s guidelines for integrating school districts.

The Marion County School Board found itself at the center of one of the most controversial issues in its history and dealing with an explosive tension that had enveloped the community. After nearly eight months of planning, public meetings, protests and boycotts, as well as teacher and student walkouts, an integration plan for the county was presented to HEW and given approval. HEW sent a letter stating that Marion County was operating “a unitary, nonracial school system” and thus met the requirements for the 1969-70 school year. The letter further commended the district for the leadership it demonstrated in meeting the provisions of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act.

The Marion County School Board found itself at the center of one of the most controversial issues in its history and dealing with an explosive tension that had enveloped the community. After nearly eight months of planning, public meetings, protests and boycotts, as well as teacher and student walkouts, an integration plan for the county was presented to HEW and given approval. HEW sent a letter stating that Marion County was operating “a unitary, nonracial school system” and thus met the requirements for the 1969-70 school year. The letter further commended the district for the leadership it demonstrated in meeting the provisions of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act.

Then, in 1978, a federal order required the district to “establish and maintain specific demographic balances and procedures.” It would take 29 years of “battling Department of Justice supervision” for the Marion County Public Schools to finally earn “unitary status” in a Jacksonville federal court in 2007.

Early Years

Those first years at the newly integrated high schools presented a long, difficult road for students, teachers, administrators and parents.

When Howard High School was closed in 1969, students were sent to the former OHS—which was renamed Forest High School—and the new desegregated school, Vanguard High, opened in 1970.

“It was the best of times and the worst of times,” David Ellspermann, Clerk of the Marion County Circuit Court, says, invoking a famous line from Charles Dickens, when asked about his experience at Vanguard. “A new school, new administration, new sports and academic teams, and new traditions, to some were seen as providing opportunities,” he continues. “However, to others, it was a loss of established community, tradition, culture and achievement, and that was not acceptable.”

Emmy award-winning nature videographer Mark Emery graduated from Vanguard in 1972. He recalled an atmosphere at the school in 1971 as unfriendly to former Howard High students, which included incidents of students waving a Confederate flag in front of the school.

Resentments on both sides fueled acts of cruelty and added to unrest, but at the same time black and white students were forging friendships that have lasted through the years.

“I had a black friend and I told him since I have red hair and other kids picked on me, we could band together and get through this,” Emery recalls.

“I had a black friend and I told him since I have red hair and other kids picked on me, we could band together and get through this,” Emery recalls.

But there was more than friction and friendship between races to consider. There was also the loss of identity and community that was inevitable given this imposed melding of cultures.

“Integration was forced,” offers former Vanguard student Gladys Krigger Washington. “We felt like black outcasts.”

TiAnna Greene, community advocate and current president of the Marion County Branch of the NAACP, says desegregation was aimed at “bridging the gap” in education, however, the system failed to provide cultural enrichment. “If you don’t know where you’ve been, you don’t know where you’re going,” Greene asserts.

She explains that while black students were able to attend previously predominately white schools and benefit from better conditions, the lack of cultural diversity and loss of connection to their communities represented a negative impact during the early years of school integration.

“We had a neighborhood environment and a sense of community” tied to black educators, says Barbara Roberts Brooks, who was set to go to OHS in 1966 under the “Freedom of Choice” option, but ultimately decided to stay at Howard High School.

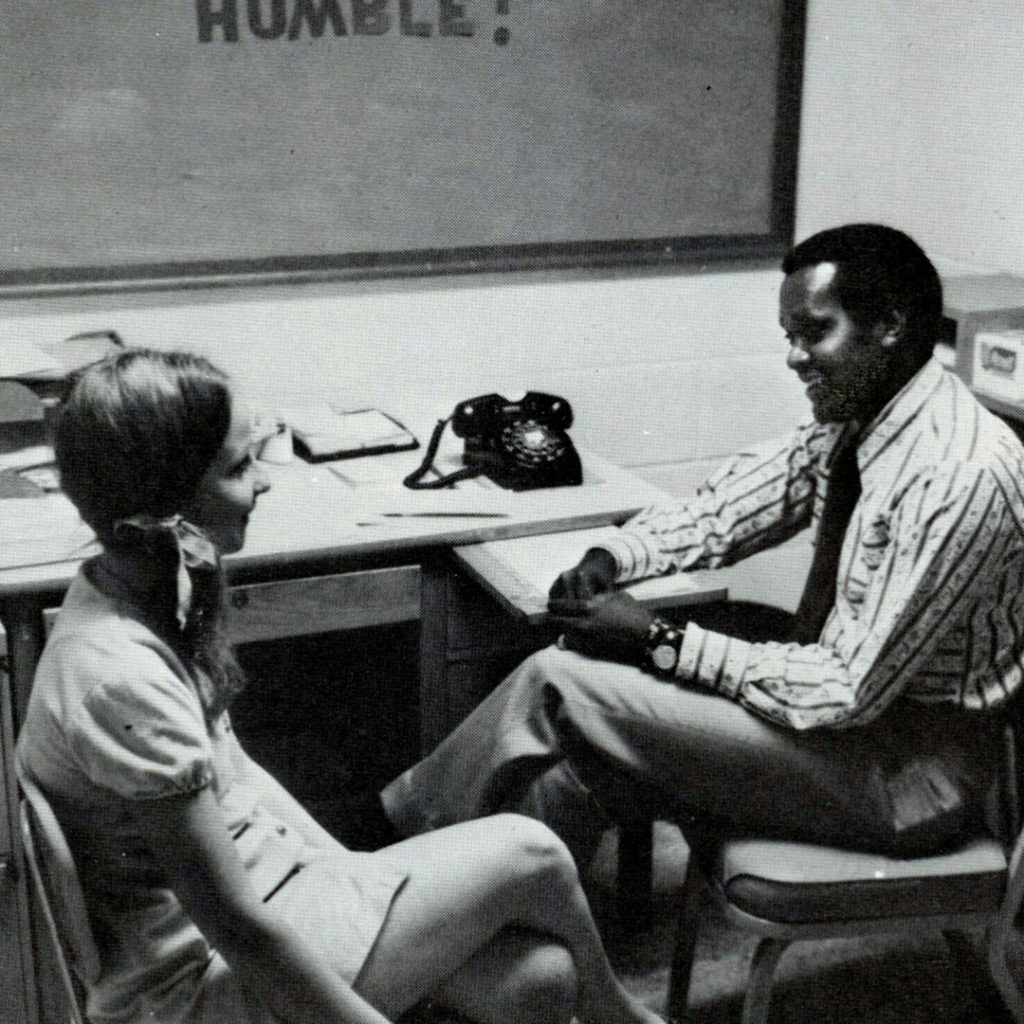

Lorenzo Edwards, a former city councilman, former president of the Marion County Branch of the NAACP and pastor of Mount Moriah Missionary Baptist Church in Ocala from 1968 until his retirement in 2018, addressed the school board during the early years of school desegregation and called for more black educators and more representation.

A Human Bridge

An important and somewhat hidden figure in creating a connection for black students to their former school and culture came in the form of William James. Now 99, he has been credited as an unlikely hero during Marion County’s school integration.

James was working as a custodian at Fessenden School and was asked to transfer to North Marion High School to act as a calming influence and to mentor black students coming there for the first time under the integration plans.

“The students knew me,” James explains. “I was at North Marion High School when the county schools were integrated. It was something I had prayed for, and I thanked God that I was privileged to see it. It was just like Dr. King had dreamed…white children and black children were going to school together and playing together. It was wonderful to see.”

“The students knew me,” James explains. “I was at North Marion High School when the county schools were integrated. It was something I had prayed for, and I thanked God that I was privileged to see it. It was just like Dr. King had dreamed…white children and black children were going to school together and playing together. It was wonderful to see.”

He recalls counseling the incoming black students to adopt a “turn the other cheek” outlook and ignore any cruel remarks or racial slurs, because some students would be friendly and some not.

Some key life advice he says he was able to impart to black students was to be “adjustable.”

“Are you familiar with an adjustable wrench?” he asks. “It adjusts to different sizes. And that’s how life is. I lived my life that way…adjustable. I had to adjust to different situations, no matter what it was. I taught people that. I would say, ‘You have that little bead on an adjustable wrench that will open it up or close it down…you can make it whatever size you need. That’s how life is. You have to adjust to the situation.’ When integration started, people were doing this or saying things, I could adjust to it.”

He recalls that when someone used the N-word to address him, even when they were asking how he was doing, he would simply respond, “How are you, white man?”

“That didn’t bother me. It didn’t take nothing from me. I just adjusted to the situation. The Bible says, ‘the Lord will make a way out of no way.’ I used that idea of the adjustable wrench so I could adjust to these situations and make my way.”

Athletics as a Bridge

George Tomyn is an Ocala native and 1972 graduate of Forest High School. His mother and father were teachers. He has served here as a teacher, principal, district school official and Marion County Public Schools superintendent. Now executive director of the Florida High School Athletic Association, Tomyn feels that while the mixture of cultures during integration was pushed on all the students, sports programs were a kind of safety valve.

“The school year from 1969 through 1970 was a stressful year for many,” he recalls. “But athletics was a great bridge builder between the white and African American students. When our teams were playing and winning, we experienced very few problems.”

Coleman also found athletics to be a bridge to connecting with his white peers.

“Having experienced the athletic arena probably endeared me far more to my fellow white students than my peers,” he admits. “But beyond my fellow athletes, I remain friends, to this day, with many white students who were in our class. Prior to integration, I dare say, I had zero white friends.”

Further Hurdles

Coleman’s challenges for racial equality continued after OHS graduation. His exceptional performance in track at OHS earned him numerous scholarship offers from NCAA colleges. In May of 1968, he was set to sign with the University of Florida (UF), but Coleman recalls his father said, “No, they are going to kill you!”

After the UF signing was announced, Coleman did indeed receive death threats, including one in a letter that read, “Dear N—–, Prepare to die. You will never make it to Gainesville,” Coleman recalls. “But I was 18 and invincible.”

After the UF signing was announced, Coleman did indeed receive death threats, including one in a letter that read, “Dear N—–, Prepare to die. You will never make it to Gainesville,” Coleman recalls. “But I was 18 and invincible.”

Coleman became the first black athlete to receive a scholarship to UF. However, he was “not greeted with open arms” and, for more than a month, he ate lunch alone in the athletic hall. Coleman says the “turning point” at UF was when he stood up after eating lunch one day and a white player, Jack Youngblood, likely the biggest man on the UF football team, appeared in front of him.

My daddy told me I was going to die and now it’s going to happen, he recalls thinking.

But rather than confronting him, Youngblood asked, “Can I sit with you?”

Coleman says the gesture by Youngblood “made a significant difference among his fellow athletes” and the two remain friends today.

Coleman feels hailing from a large family and learning the “God given gift of agape love” and love of family and humanity was key to his success as a student and athlete.

“I knew at an early age that I was ultimately in charge of whatever was going to happen to me, so I took control of that and ran with it. Another key component was growing up in Ocala during the Civil Rights Era in America. The deep south was a hotbed of racism, and Ocala had its share of racists to contend with. That was certainly no vicarious learning situation,” Coleman asserts. “It was all firsthand experience.”

He feels his family members and friends lived through the fearful times during the civil unrest in the 1960s and 1970s by supporting, encouraging and loving each other.

“What being among the first African American students to attend an integrated school in Ocala taught me was many valuable lessons about the art of survival, and the never-ending need for prayer,” Coleman shares.

The Road Ahead

Tomyn believes that desegregation truly led to better opportunities for students and a richer educational environment here in Marion County, because of the diversity that resulted from the integration of schools and how that has been further cultivated over the years.

“In my 40-year career as a teacher, coach, school administrator and district administrator, our district changed for the better in many ways,” he asserts. “When children of all ethnicities and races had the opportunity to attend school from kindergarten through 12th grade, a more ‘integrated’ atmosphere evolved. Teachers and administrators of all races working side by side delivered a better educational experience for all students because there was better understanding and appreciation of our differences. I believe that our educational system will continue to improve over time. I received a great education as a student in Marion County public schools and my own children, likewise, received a great education. I am very proud to have been a part of our district’s history. A lot has changed since the ‘60s and ‘70s and I still am very proud to call Ocala and Marion County my home.”

“In my 40-year career as a teacher, coach, school administrator and district administrator, our district changed for the better in many ways,” he asserts. “When children of all ethnicities and races had the opportunity to attend school from kindergarten through 12th grade, a more ‘integrated’ atmosphere evolved. Teachers and administrators of all races working side by side delivered a better educational experience for all students because there was better understanding and appreciation of our differences. I believe that our educational system will continue to improve over time. I received a great education as a student in Marion County public schools and my own children, likewise, received a great education. I am very proud to have been a part of our district’s history. A lot has changed since the ‘60s and ‘70s and I still am very proud to call Ocala and Marion County my home.”

Former MCPS board member Bobby James, a 1966 graduate of Howard High School, thinks we still have a way to go in ensuring equality for minorities in our schools.

“I’d like to see more encouragement of and participation by minority students in high performance programs like the International Baccalaureate and Honors programs,” he explains.

On the Other Side

While school integration broke down the official barriers for black Americans to gain access to an equal education, achieving this ideal has never been easy or simple. Today, the debate continues in communities across the nation, among policy makers, educators, parents and students, on how to close the achievement gap between minority and white children.

When asked to consider the impact of desegregation and the current race crisis in America, our pioneers of integration are united in their thoughts.

Of the black students who participated in “Freedom of Choice,” Capshaw says, “I admired them and appreciated what they did for our little town and our country.”

Of the black students who participated in “Freedom of Choice,” Capshaw says, “I admired them and appreciated what they did for our little town and our country.”

Regarding the future, she urges, “So much more work needs to be done. We’re in the middle of it. A lot more needs to be done for race relations in this country.”

Rhone echoes the sentiment.

“We came away from that time, but then we got stuck,” she declares. “There’s so much more that we know has to be done. And we won’t just settle for, ‘Well, some of it was done. That’s okay.’ More has to be done.”

Walker believes we need to dig deeper and summon up that same courage and generosity of spirit that brought us through other tumultuous periods in our history.

“We are all ‘of the human race’ before we are any other race. By being part of the human race, we should be compelled to embrace everyone,” she asserts. “As I said before, there are indeed more similarities than differences between us. And once we see ourselves in other people, we can share in one another’s plight and seek to help one another.

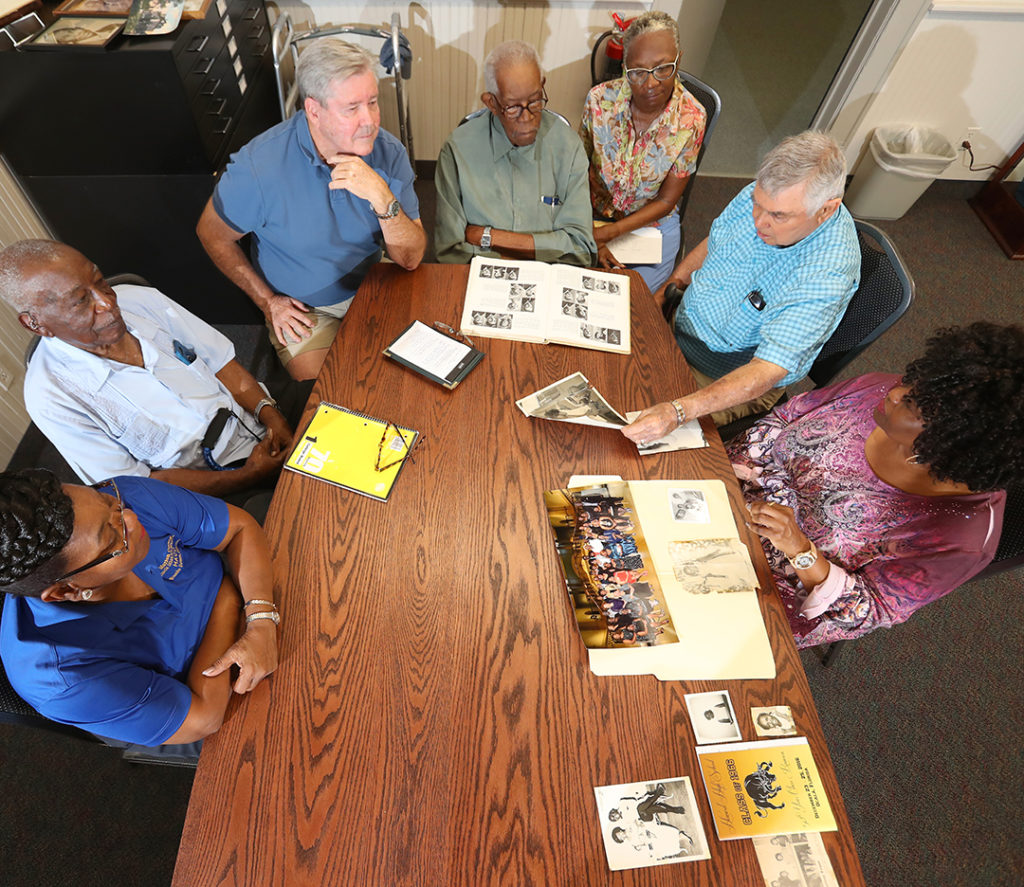

Our Thanks to the Following:

The Historic Ocala Preservation Society (www.historicocala.org) has several years of newspaper clippings that were utilized in the creation of this story and recording secretary and board member Brian Stoothoff facilitated access to those materials.

Staff at the Marion County Museum of History and Archaeology assisted with document research and provided archived newspaper clippings for this article.

Staff and volunteers at the Black History Museum and Archives of Marion County, located in the Howard Academy Community Center, contributed information to this article.

Kevin Christian, Marion County Public Schools Director of Public Relations and Multimedia Productions, provided historical documents for this article.