To the Tuskegee Airman, the popular wartime song became the motto to get them through some of the toughest military training ever known and to overcome the barriers that American society had placed on them. Three local members of this elite group—Hal King, Gil Langford, and Robert Walker—were recently awarded the nation’s highest civilian award, the Congressional Gold Medal. It was long overdue.

They live quiet lives now. Hal King and Gil Langford in The Villages and Robert Walker in Silver Springs Shores are humble men who love talking about their children and grandchildren more than they do about themselves. You would never know they are heroes—true American heroes who fought for more than just their country. They also fought for respect.

These three gentlemen were members of the famed Tuskegee Airmen during World War II.

The government selected Tuskegee Institute in southern Alabama to conduct a military pilot training “experiment” because of the school’s excellent engineering program and successful Civilian Pilot Training Program. Air Corps officials built a separate facility at Tuskegee Army Air Field for basic and advanced flight training for black pilots. The training was tough and many politicians hoped the program would fail.

But it didn’t.

Those cadets who passed—later known as Tuskegee Airmen—fought as a segregated unit in the U.S. Army Air Corps, the forerunner to today’s U.S. Air Force. They are remembered as heroes who successfully completed more than 1,500 missions over North Africa and Europe and whose success paved the way for integrating all of America’s armed forces.

“Although our nation was segregated during World War II, nearly 1,000 black Americans stepped forward to serve in a special Army Air Corps program to train as pilots,” says Congressmen Cliff Stearns, whose office honored the Tuskegee Airmen who live in his district last summer. “They went on to establish an astounding record in combat.”

The fighter pilots, whom the Germans called “Black Birdmen,” escorted heavy bombers toward their targets. The Tuskegee pilots in the faster and lighter fighter jets fought off enemies who tried to shoot down the bombers. The Allies called them “Red Tails” or “Red-Tail Angels” because of the distinctive crimson paint on the vertical stabilizers of their aircraft. The Tuskegee Airmen’s success was well-known throughout the Corps, and bomber crews requested Red Tail escorts whenever possible.

This is their story, as told by three area residents who witnessed it all.

‘My First Real Whack Of Racism’

Hal King was a football and basketball player at Long Island University when the war began. He knew he’d eventually be drafted and his coach recommended the experimental program at Tuskegee.

“I always thought about flying,” says King. “I knew this was an opportunity.”

Born and raised in Brooklyn, N.Y., the 20-year-old King was apprehensive when he learned the training location was in Alabama.

“All I knew about the South was what I had heard and read,” he says. “This was my first real ‘whack’ of racism, but I kept my eyes on the goal of flying.”

King eventually became a lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Air Force and ended up at the Pentagon. He later became the deputy director for the Delaware River Port Authority.

Davis acknowledged that the training was harder on black pilots. The prevailing attitude in the military was that they were supposed to fail because they didn’t have the ability.

“Those who thought color had something to do with ability soon found out differently,” he recollects.

The Tuskegee Airmen often told each other, “Straighten up and fly right,” also the name of a popular wartime song.

“It didn’t mean just flying,” King says. “We were learning how to be officers.”

When the war ended, King returned to college and received a degree in accounting. He was recalled to active duty in 1948 and became a commissioned officer.

While at the Pentagon and before retiring from the military in 1971, the father of four was able to watch the “comings and goings” of his oldest son who was then an Air Force pilot in Vietnam.

“The Tuskegee Airmen blew open the doors of the Air Force for African-Americans,” says King with a smile.

‘A Tight Group’

When Robert Walker was a little boy in Detroit, he made model airplanes. He used money from his paper route to buy the kits and he had so many that they hung from his ceiling.

Maybe it was that early interest in airplanes that led him to pursue the Tuskegee training program when he was drafted in 1943. After graduating from high school in 1938, Walker serviced office equipment, including teletype machines, a trade that he learned from his father.

“Everything that was happening about the war came over those teletypes,” he remembers. “I couldn’t tell anyone about what I had read. A slip of the lip would sink a ship.”

Walker read about the pilot training program, and he knew some boys who had left Detroit to go to Tuskegee. He also knew that he too wanted to fly.

He passed a battery of “very hard” tests at Keesler Field in Biloxi with a 100-percent score.

“I thought I was the only one to ever make a 100 until I saw the movie,” he says. “Apparently, there were some ahead of me who also had perfect scores.”

At Tuskegee Institute, the training was as tough as the movie Tuskegee Airmen indicated. The program was designed to test the men’s ability to take adversity. The training also helped them rise above the issues of segregation and racism.

“We learned that you can’t fly with that kind of anger,” Walker explains.

Walker also remembers the day that Mrs. Eleanor Roosevelt visited Tuskegee Institute and how tight security was.

“The movie was accurate, except that it didn’t show how much planning really went into her visit,” says Walker, who went to Utah to watch the filming of the 1996 movie.

Walker says with a chuckle that he was a “late bloomer” as a Tuskegee Airman.

“I went over as a replacement pilot two months and two days before the war ended,” he says. “The Germans heard I was coming and decided to quit.”

The young airman spent the last couple of months of the war in Ramitelli, Italy, the home base for the Tuskegee Airmen. He describes it as the “boondocks” near the German line, but the airmen ate very well and shared plenty of camaraderie.

“We were a tight group,” he says.

Walker stresses that the Tuskegee Airman encompassed more than pilots. The group included navigators, tactical officers and ground support.

“Anyone who helped us get off the ground had to be a person of color,” Walker explains.

After the armistice, Walker completed his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in business administration. He taught business and later was director over five vocational centers in the Detroit area.

At 87, Walker says life has been good. He’s traveled around the world twice and visited Iraq in 1975 as an educational advisor for a vocational program. He and his wife, Alyce, celebrated their 60th wedding anniversary last June. They first came to the Ocala area in 1986 and moved here permanently in 1990.

Walker is still a member of the Tuskegee Airmen, Inc., which includes friends and descendants of the original Tuskegee Airmen. The national club was instrumental in getting the long-overdue recognition for the Tuskegee Airmen.

President Bush presented the Congressional Gold Medal to the Tuskegee Airmen in the spring of 2007. Walker was one of the few Floridian survivors who made the trip to Washington, D.C.

“It was like a big family reunion,” he says. “I saw guys from 1945, including some who had been close friends.”

He’s glad the recognition came when it did.

“If they had waited any longer,” he says, “there wouldn’t have been any of us left.”

‘I Wanted To Be A Pilot’

At 81, Gil Langford is the youngster in this group. He didn’t see combat action like Walker and King. In 1943, he was still in high school in Indiana and member of the Civil Air Patrol. Upon graduation, though, he went into the service at the insistence of his recently widowed mother. He volunteered for the Army Specialized Training Program and took his oath in August 1943.

He was sent to West Virginia State College where he enrolled in classes, volunteered for the Aviation Cadet Program, and took private flying lessons. After the first semester, he was sent to Keesler Field in Biloxi to complete qualification tests for flying. He qualified equally for pilot, navigator, and bombardier training. Next stop was the Tuskegee Institute, where he was assigned to the pre-flight detachment.

When Langford signed up for the Army Air Corps, he really wanted to go to Randolph Air Field in Texas. His second disappointment came shortly afterward when he was told he would be going to bombardier school.

“I couldn’t go to Randolph because of the color of my skin,” he says. “And I wanted to be a pilot.”

When Langford arrived at the Tuskegee Institute, he knew—because of his schoolteacher mother and pharmacist father—that education was the key to overcoming obstacles. He doesn’t recall hearing the term, “Tuskegee Airman,” while at the school or later on active duty.

“The men involved thought of themselves as pilots,” Langford says. “The Tuskegee label came later.”

According to the Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Museum, the name “Tuskegee Airmen” was coined in 1955 by Charles E. Francis, one of the African-American pilots who trained in Tuskegee during WWII.

From Tuskegee, Langford was transferred to Hondo, Texas, to be trained as a navigator-bombardier. In 1945, he graduated and was commissioned as a second lieutenant. For the next two years, his assignments included being a bombardier instructor and serving as an assistant weather officer.

After leaving active military, Langford joined the reserves and returned to Purdue University, where he received an engineering degree in 1951. He had a 25-year career with General Electric. He later became a consultant and formed his own company, Management Technology Associates. He moved to The Villages in 2004.

Langford didn’t think much about his Tuskegee experience until the call came last year that he was going to receive the Congressional Gold Medal.

“Many people—those who were in combat or POWs—were much more deserving than I was,” he says. “They demonstrated that skin color did not determine if they could operate complex machinery like an airplane.”

Want To Know More?

The Tuskegee Airmen—The 1996 HBO movie was a catalyst to get long-overdue recognition for the legendary pilots who sacrificed so much for a country that treated them as second-class citizens. Starring Laurence Fishburne, the movie is a docudrama that Tuskegee Airmen say is an accurate portrayal. The movie is available on DVD.

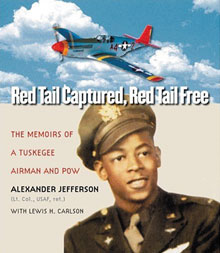

Red Tail Captured, Red Tail Free by Lt. Col. Alexander Jefferson, USAF, Ret.—A memoir about Jefferson’s experiences both as a Tuskegee Airman and as a POW in Germany. A close friend of Ocala’s Robert Walker, Jefferson was an amateur artist when he was shot down on his 19th mission. The book also contains his drawings and illustrations from that period. (Fordham University Press, 2005)

Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Museum—Part of the National Park Service, the museum is located at Moton Field in Tuskegee, Ala. www.nps.gov/tuai

Tuskegee Airmen, Inc. (TAI)—A non-profit organization with 50 chapters nationwide dedicated to honoring the accomplishments of African-Americans who participated in air crew, ground crew, and operations support training in the Army Air Corps during WWII. www.tuskegeeairmen.org