There’s got to be an easier way to make a living. Actually, there are thousands of easier ways. But for John Claytor, none of them offers the challenge and satisfaction that he finds in harvesting long-lost sinker logs and turning them into unique pieces of furniture.

Logging has long been recognized as one of the world’s most dangerous professions. Add the daunting element of underwater recovery and you’ve got “deadhead” logging, one of the most difficult, labor-intensive timber jobs you can find.

Claytor wouldn’t have it any other way.

With a reputation second to none in this unusual field, the Ocala native recovered his first underwater log in 1970 and has been a full-time deadhead logger since 1999.

Nationwide, there are probably fewer than 100 people doing what Claytor does. His wife, Cathy, helps with the bookkeeping end of their business, Deadhead Logging, while his son, John Jr., also assists. Claytor refers to him as the “computer guru.”

Deadhead logging isn’t about pulling fallen trees out of a swamp or river. It’s a whole lot more involved than that. And for clarification, these loggers aren’t going after trees that just fell in the water but, rather, sunken logs and timber that have already been cut, most of them over 100 years ago.

Back in the late 1800s, when Florida was much more “wild and woolly” than her civilized 21st century self, the peninsula was covered with abundant stands of old growth longleaf pines and swamps boasted giant cypress trees, some thousands of years old. All that natural wealth attracted the attention of logging companies eager to turn timber into cash.

After the daunting accomplishment of felling the trees with axes, the loggers then had to transport the enormous logs to a saw mill. Before the railroad, the fastest way to move the hand-cut logs was by water.

“The logs were cabled or chained together and floated downriver to the mill,” Claytor explains. “Sometimes the logs weren’t dry enough to float and would start to sink, so the logger would cut it loose and sacrifice one or a few to save the rest. That’s how many logs were lost.”

The Florida Department of Environmental Protection, which claims ownership of most logs because they are located on sovereign submerged lands, estimates that about 10 percent of cut trees sunk during the transport process. Once on river bottoms, the lack of oxygen and cool, tanic waters did a remarkable job of slowly preserving the lost timber over the decades.

It’s not certain how or when someone recovered the first deadhead log and realized how versatile and valuable the wood they yield is, but now they’re highly regarded and can bring as much as 10 times the price of conventional lumber. Their tight grain, durability, resistance to rot and impressive color range make the submerged logs truly unique. Making them all the more desirable is the fact that they’re limited—and hard to come by.

“They call this product ‘pre-harvested timber.’ This is a non-renewable resource; when this wood is gone, it’s gone,” says Claytor. “Today, it’s become popular to use reclaimed wood from old buildings, but the rarity, strength and beauty of this river wood makes it even more valuable. There’s so much time, effort and money that goes into getting it.”

Hitting The Water

“Getting it” is precisely what fuels Claytor. His passion is obvious as he shows the fruits of his labor and talks about the challenge of finding sunken logs, let alone recovering them. Fit and athletic, Claytor’s physical condition and sharp wit belie his 67 years, but his work-worn hands are a testament to the dangerous and exacting work he does on a daily basis.

In 1965, Claytor was just a junior at Lake Weir High School when he started scuba diving in Florida’s rivers. On his dives to find arrowheads, old bottles and other antiquities, he kept noticing fallen logs. He asked around and found out a few people were trying to salvage them and sell the lumber. Claytor decided he wanted a piece of the action of this resource that could never be duplicated.

After a short stint in the Army, Claytor became a manager for mobile home plants. For many years, that remained his main job while he pursued his underwater logging business on the side. By the time he was ready to log full time, Claytor had become a master of finding and recovering submerged logs. Modern technology has enhanced the methods of reclaiming sinker logs.

“When underwater logging started, you either had to find them in shallow water or, if the water was clear enough, you could look down and see them on the bottom. In the early days, we found them one by one,” he recalls. “Now, technology has stepped up the treasure hunt. We’re finding logs we never would have found before without experience, knowledge of where to look and learning how to use technology. Some of those logs are buried several feet below the river bottom.”

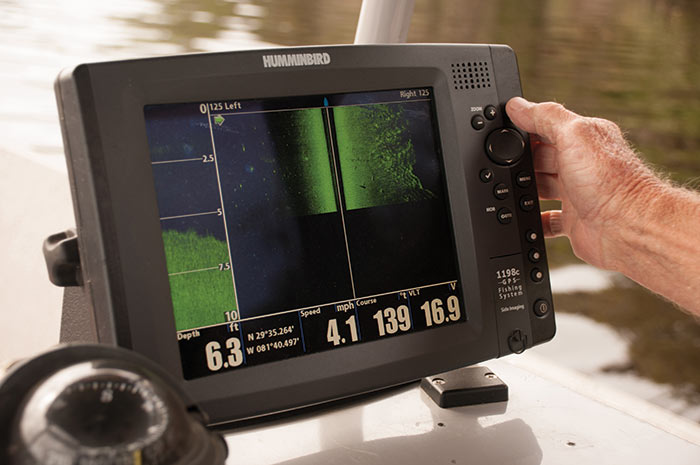

Claytor utilizes side scan sonar to identify whether or not the object under water is a tree or a pre-cut log, meaning it was harvested at one time. As he explains, it’s illegal to take a tree that fell into the water on its own. He can only take pre-cut trees that were harvested before the current laws were established. In other words, he’s “re-harvesting” trees someone else harvested—and lost—many decades ago.

Half the battle is knowing where to look, a skill that can only be mastered with time and experience.

“It pays off to do your research,” says Claytor, who has logged over 10,000 underwater hours. “I always look for old saw mill sites because you often have a good chance of recovering logs that were lost or left behind. It wasn’t uncommon for a mill to close when money or help ran out, and they just left, often leaving wood behind. I’ve found several places in the Suwannee River with hundreds of logs. In Dunnellon, I found an old mill site in the corner just above the bridge where the Blue Gator is now. I pulled hundreds of heart pine logs out of that spot; they were stacked 25 logs deep.

“At one time, Wilson Cypress on the St. Johns River in Palatka was the largest producer of cypress in the world. This was around the late 1800s and early 1900s. I researched this and found thousands of board feet of cypress logs and boards there. Murphy Creek, just south of Palatka, is another spot where I’ve gotten great logs out of an old mill site.”

Some of those were “extreme” logs, meaning they’re more than 30 inches in diameter and 30 feet, or longer, in length.

The Legalities Of Logging

Just being in the water to search for deadhead logs requires multiple steps beforehand.

Claytor had to be certified as a master deadhead logger, sign a use agreement with the state, plus apply and pay for multiple permits. He’s also required by state law to hire an archeologist who goes to the state master file in Tallahassee and researches his permitted areas. If the archeologist finds that an area may have sites of historical value, Claytor is prohibited from logging in that specific part of the river. Many water bodies, such as springs, are completely off limits to loggers.

“There are 13 agencies that have laws affecting my business,” says Claytor, adding that all of his logs are legally recovered from Florida rivers. “You can’t just go out there and harvest old wood. I have to get a state permit every year and a separate permit for every 20 miles of river stretch I operate in. Right now I have over 200 miles of permitted stretches of water that I’m working.”

And locating the submerged logs is only the first step. The next challenge is removing them.

Using a set of grapples—they look just like a huge set of old ice tongs—on one of his four boats, Claytor dives down and hooks onto the log. Then he uses the barge to pull and break the log loose, which isn’t as simple as it sounds. With some logs, it literally takes days to work them free of the mud and silt on the river bottom.

“Once we get it free, we ‘stage’ it, which means we get the log to the shore and put a buoy on it with my permit number, just like you’d have with a lobster or crab trap in Florida waters. The state tells us where we can take logs out of the water; we either have to own the site or have written permission from the land owner or the state, if it’s state land,” says Claytor. “After we get logs to the staging area and stock pile them there, we bring a truck and trailer to pick them up and transport them to where they’re going to be stored or milled. There’s a lot of handling before you get ready to cut a log, let alone build something out of it.”

Unfortunately, on occasion, people—call them “log rustlers,” if you will—steal logs out of the staging area before Claytor picks them up. When that happens, all his hard work is for naught, but there’s not much he can do about it.

From Log To Lumber

Once the massive logs, some of which weigh 8,000 pounds or more, are in his possession, Claytor must have them dried before he can do anything with them.

Cypress hold an astonishing amount of water. Claytor notes that 1,000 board feet of cypress will contain 310 gallons of water before being dried. This is best done by placing the milled wood on sticks and letting it air dry, but you can’t be in a hurry. It likes to dry slowly; 1 inch of thickness takes about one year to dry.

Pine, on the other hand, is kiln-dried. Claytor says it takes anywhere from two to four weeks for heart pine boards to dry down to a moisture content you can work with. (Keep in mind this is not the same pine you’ll find at your local lumber store. This is from old growth longleaf pine, and there are only a few thousand acres of virgin old growth pine left in the country today.)

In the past, Claytor sold the dried lumber to carpenters, homeowners and woodworkers. Then, about a decade ago, he decided to use it himself and started making his own furniture in his second business, Water Wood Originals.

As if salvaging this remarkable lumber wasn’t enough, now Claytor makes one-of-a-kind furniture, each piece with its own distinctive history and guaranteed authenticity. Anyone who buys one of his creations gets the entire history of the wood he made it from, something you can’t get at one of the “big box” furniture stores.

“I love the thrill of the hunt of finding logs, but I also get a lot of satisfaction from making a unique piece of furniture that someone can incorporate into their home and enjoy,” says Claytor, who has 30 years of saw mill experience on the old mill he bought and rebuilt on his property. “When you mill this lumber, it’s just like the day the tree was cut down. You’re getting the same piece of wood the man who cut it down 100 years ago was hoping to have. It’s like opening a box of Cracker Jacks and getting the prize.

“There’s no limit to what you can dream up with this material,” adds Claytor, who just finished redoing his own kitchen with cabinets made from cypress milled from logs he salvaged from the Ocklawaha River.

When crafting a piece of furniture, Claytor likes to leave telltale signs of the wood’s history, such as the axe-cut end on a heart pine bench.

“Axe cutting stopped around 1890, so anything you find axe cut was harvested prior to that. Then they went to two-man saws,” he notes.

The edges of one table made from cypress display the unique pattern left by ship worms, which eat the outside of the tree. Claytor finds cypress with this unusual appearance predominately in the salt and brackish water of the St. John’s basin.

In addition to stunning tables, benches, shelves and stools, Claytor also makes intricate carvings from heart pine, the hardest medium of wood to carve, thanks to its high pitch and resin content.

His workshop is brimming with things he’s found underwater over the years, including shark’s teeth, ancient bottles, arrowheads, fossilized mastodon and mammoth teeth. One of the most curious things he ever found was a copper moonshine still discovered on the bottom of the Suwannee River.

Anything he finds of historical value, Claytor donates to schools, museums or historical societies so the people of Florida can benefit. The moonshine still, for example, was donated to the state and is on display in Tallahassee.

Although many men his age have quit working and are spending their days on the golf course or pursuing hobbies, Claytor has no interest in retiring.

“I’m still working as hard or harder than I’ve ever worked. I’m scared to retire,” he laughs. “I’ve acquired a lot of knowledge, and I want to continue putting it to use. I feed on learning, and I love finding out about new things.”

No one can be sure how many deadhead logs lie submerged in Florida’s rivers, still waiting to be salvaged. Claytor knows there’s a limit to the number of logs out there, and that, someday, they’ll be gone. Until then, he has every intention of staying in the hunt.

Learn More › deadheadlogging.com › waterwoodoriginals.com