No other neighborhood in America can boast two national championships in basketball and one in football except Urban Meyer’s and Billy Donovan’s in Gainesville. In his recently released authorized biography, Urban’s Way, the Gator football coach tells why these two top coaches also became pretty good friends.

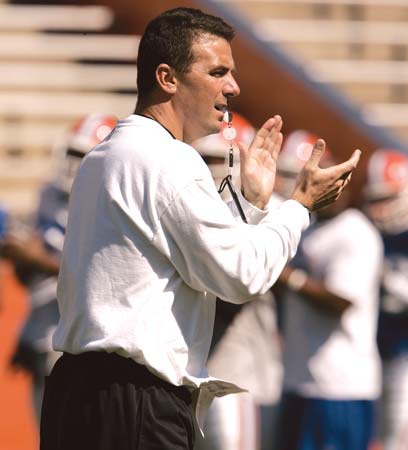

“I get out of my office, walk down the street, and visit

with the best basketball coach in the game,”

says UF football coach Urban Meyer.

Photo courtesy UF Athletics

The homes of Urban Meyer and Billy Donovan are maybe half a football field apart in a neighborhood too exclusive to be called a subdivision. Only five houses sit on large, expansive lots—all two-story, some with circle drives, most with white columns.

To reach the Cul-de-Sac of Champions, one must travel through contiguous traffic roundabouts in southwest Gainesville on a narrow, two-lane road framed by moss-draped oaks. Inside the 10-foot tall iron gate, the Meyer home sits off to the left, painted olive green with stone elevations. A basketball backboard is in the driveway, with a volleyball net and batting cage in the back, a screened-in, kidney-shaped pool, plus an air hockey table and pool table in the rec room. The house has a distinct, Florida-style garden décor with a country flavor, though the area outside the gate is well-populated and a grocery market and strip mall are right down the street.

The expansive, gray-and-white home with the stone-and-wood façade at the end of the Cul-de-Sac of Champions belongs to Billy and Christine Donovan, who helped recruit the Meyer family to Florida and to their neighborhood—and their school.

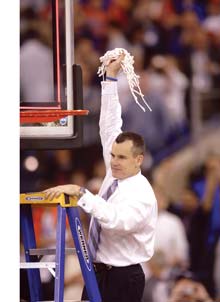

Billy Donovan’s success became the business model for Meyer’s

2006 national championship football team.

On a late-night ride through the neighborhood, Donovan will notice that Meyer’s car still isn’t parked at his house. Their sons often play with each other, but the dads not so much. On Fridays during the off-season, Urban walks son Nate down to the bus stop, where they play a game with Bryan Donovan, rewarding the first to spot the bus.

“Bryan has a lot of my money,” Urban quips.

Billy and Urban are good friends—maybe not best pals, but better than just mere acquaintances and neighbors—both by-products of a strong Catholic upbringing. Urban Meyer totally gets Billy Donovan and vice versa.

Meyer chose to live on the Cul-de-Sac of Champions quite by accident. He had tried to buy the home of Spurrier, but the Ol’ Ball Coach didn’t want to sell. Meyer’s admiration for Spurrier was not the motivation behind his request, he says. It was more a case of needing a pre-built house right away.

But without the help of the Donovans, getting located and building a new house would have been far more difficult.

“Christine and Shelley were really involved in the whole deal,” Urban remembers. “We built a home.”

The Donovans’ mentoring didn’t end there. Impeccable timing allowed Meyer to peek inside Billy’s laboratory for a clinic on team chemistry at the group affectionately known as the Gator Boyz, who were crafting a blueprint for champions. Donovan’s success became the business model for Meyer’s 2006 national championship football team.

“I still think a lot of our success of that whole ’06 team was because we got to experience one of the greatest basketball teams ever to play the game—the most unselfish, probably, I’ve ever seen,” Meyer says. “I became a better coach watching that team. I bent Billy’s ear to death.”

They are as different as they are similar, virtually the same age, with Meyer 11 months and 29 days older. This prized perfecta is also the highest-paid duo in college sports.

One is an overachieving gym rat from Rhode Island via Long Island who became a boy-coach with a baby face that looks as if it belongs inside a uniform instead of a Jack Victor suit, a Rick Pitino protégé who soon transformed his on-the-job training skills into championship basketball.

The other is the wunderkind from the Woody Hayes/Earle Bruce coaching tree, a hard-charging young assistant who paid attention and took copious notes, then collated them into a manual of innovative techniques as he moved up the coaching ladder toward his dream. Meyer is still tethered to father-figure coaches such as Bruce and Lou Holtz, both of whom he calls regularly.

During the fall of 2005, in his first season at Florida, Urban suddenly became distressed by some issues he felt might be less common to those two wiser, older coaches. That day he was overwhelmed by the lifestyle problems of his players—drugs, alcohol abuse, etc.—when he remembered that his basketball coaching friend had a file on behavioral problems thickened by more than a decade of experience.

During the fall of 2005, in his first season at Florida, Urban suddenly became distressed by some issues he felt might be less common to those two wiser, older coaches. That day he was overwhelmed by the lifestyle problems of his players—drugs, alcohol abuse, etc.—when he remembered that his basketball coaching friend had a file on behavioral problems thickened by more than a decade of experience.

“I was so upset that I got out of my office and called Billy and said, ‘You got a minute?’ He said, ‘Yeah, what’s wrong?’ And I said, ‘I need to talk to you.’ I had a heart-to-heart with Billy for about an hour and a half.

“You sometimes have to spend thousands of dollars to get meeting time with someone [like that],” Meyers continues. “I get out of my office, walk down the street, and visit with the best basketball coach in the game.”

After the spring of 2006, as Meyer was prepping his team for what would be a championship run, he tapped into the excitement on campus about the basketball team’s success. Billy made what Urban called “an extremely passionate speech” to the football team. That day Meyer learned the importance of breaking down seasons by segments.

“I use that all the time now,” Meyer says. “On our bowl preparations, I don’t go anything beyond four- or five-day segments because you lose the players.”

Meyer adopted Donovan’s idea of a new psychological approach on a season schedule—“It’s only 107 days”—as opposed to 12 games or six months.

“We used that big-time, even on our highlight videos,” Meyer says. “That all came from Billy.”

To reciprocate, as March Madness 2007 approached, Meyer, his staff, and players signed a poster, “Go get ‘em—we’re behind you,” and sent it to Donovan’s Gator Boyz. The poster counted down the 17 days to the title game and each time the basketball players left the room they touched it for good luck.

To reciprocate, as March Madness 2007 approached, Meyer, his staff, and players signed a poster, “Go get ‘em—we’re behind you,” and sent it to Donovan’s Gator Boyz. The poster counted down the 17 days to the title game and each time the basketball players left the room they touched it for good luck.

They have similar coaching styles. Both believe in directly challenging players, Meyer perhaps even more so. Life as a Gator football player begins with throwing your press clippings away and taking a quick inventory of your shortcomings. Billy Donovan can respect that and agrees that Meyer’s way is a quick primer on learning how to compete.

“These kids think they understand competition,” Donovan says. “When they are highly touted—and they’ve been billed or dubbed as the next NFL star or next NBA star—there can be a lot of easy ways of going through.

“I think what Urban is doing every day is creating [competitive] confrontation out on the football field,” he continues. “I don’t want to say it’s tough love—it’s reality of the way it is.”

Donovan praises Urban for making his athletes earn their place, such as achieving the Champions Club, and for the freshmen’s indoctrination of their stripe. All incoming freshman start with a black piece of tape on their helmets, later removed in a battlefield promotion.

“You need to earn your way,” says Donovan. “There’s merit in that.”

Given their similar philosophies about coaching, they make excellent sounding boards for each other. Donovan and Meyer have developed the verbal “bounce” pass into an art form, whether it’s a conversation about how to be a better dad or how to be a better coach.

So while there is a good bit of basketball in Florida’s football these days, there is also some football in the basketball program—especially on the Cul-de-Sac of Champions.

Want To Read More?

Buddy Martin is the executive editor of Gator Country magazine and its Web site, as well as executive producer of Gator Country Radio. Urban’s Way, his authorized biography on Urban Meyer, hit bookstores on Sept. 2. Go to gatorcountry.com for a personalized, autographed copy.