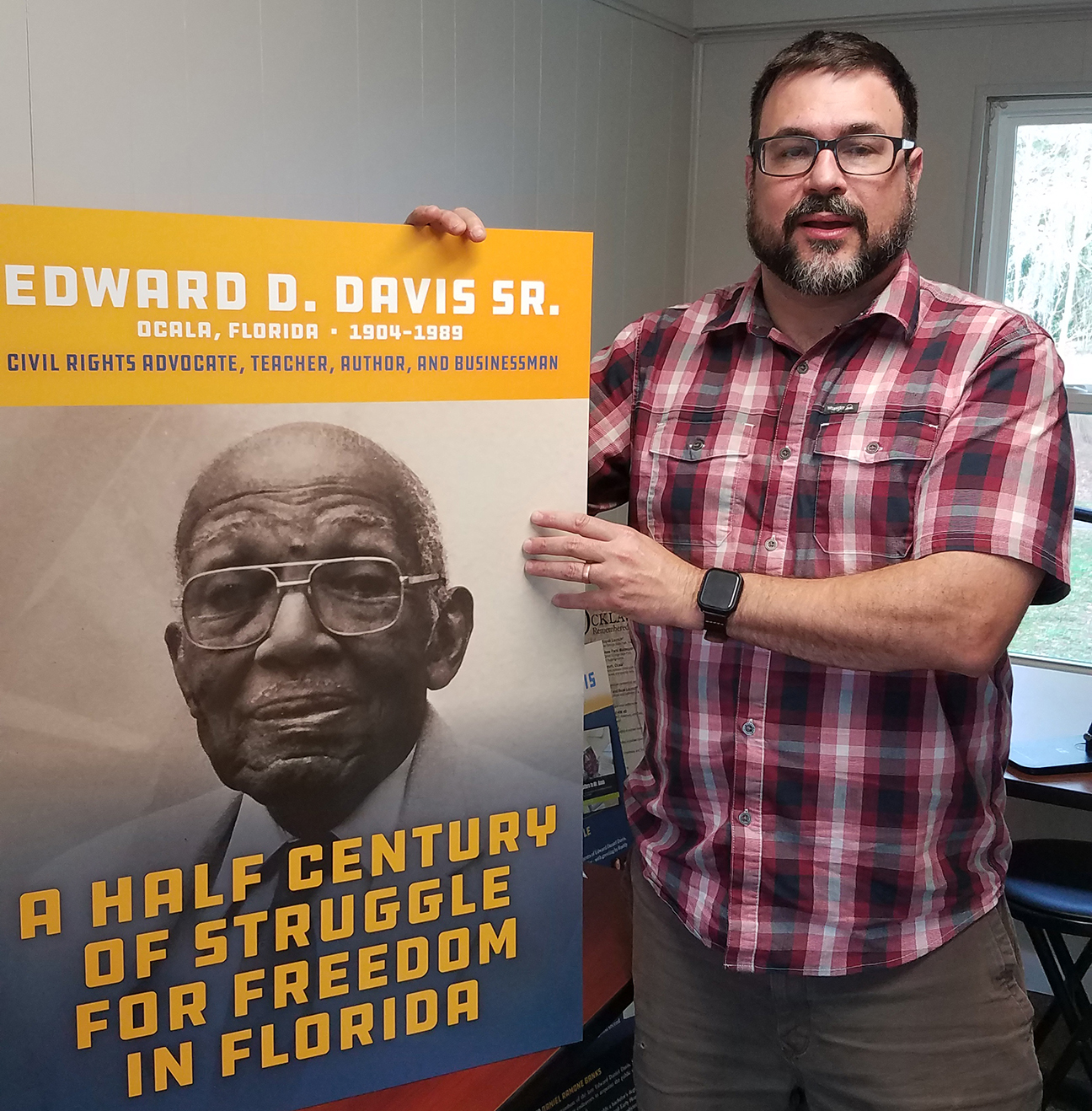

Meet the descendant of one of Florida’s notable civil rights leaders, who keeps his grandfather’s legacy alive through books and exhibits.

Daniel R. Banks is an author, elder and family historian, whose Edward Davis exhibit retells Florida’s formidable past and path to progress.

Banks grew up captivated by the stories told at the feet of his older relatives.

“They had great memories,” recalls Banks, “especially of dates. They could tell you something that happened on February 14, in 1940.”

With a story, a wealth of information was transferred into Banks’ heart, which beats unremittingly.

After a 30-year career in early childhood development, Banks retired but still labors part time in the field. He has also authored several books on various topics, ranging from the welfare of young Black boys, to travel and, of course, to his own family’s genealogy.

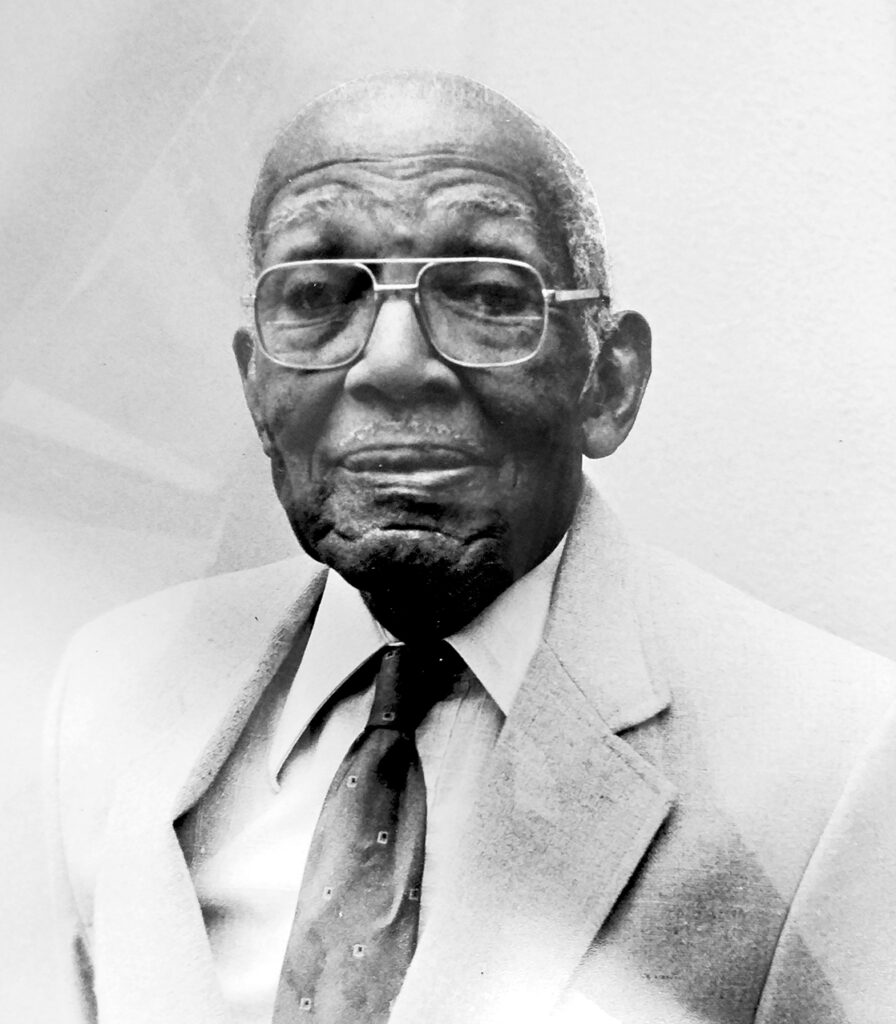

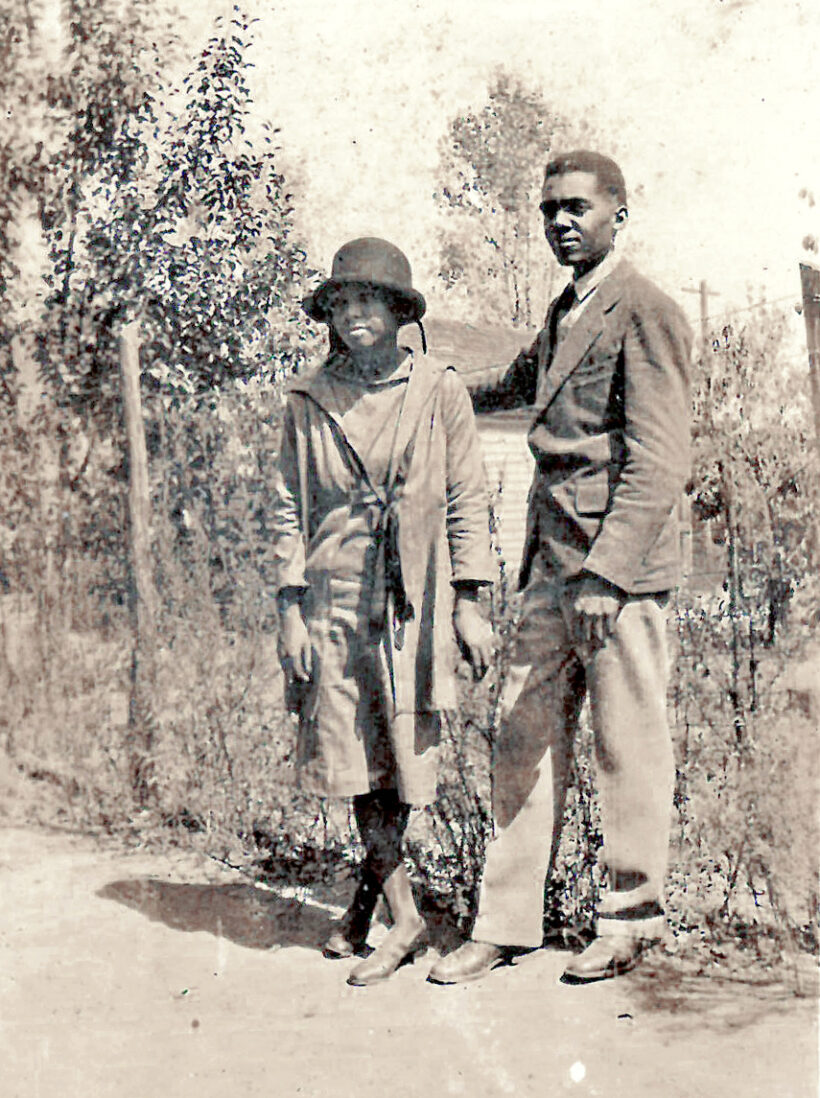

It was during a visit to his grandfather’s home, when Banks was 21 years old, that his passion for the latter topic was sparked. While fumbling through books in his grandfather’s study, he came across several curious mentions of his “highly regarded” grandfather—someone who, until that moment, Banks was unaware had such a storied and esteemed past. That’s when his grandfather, Edward Daniel Davis Sr., a former educator, lifelong civil rights leader, and successful businessman, provided him with an in-depth “history lesson” about his life and the names and stories of his formerly enslaved ancestors.

Banks recaps how he “sat with pen and paper in hand” and took note to collect as much as he could. Only one other male relative, his cousin Chester A. Sims, gathered as much of the history. “Mr. Davis” (Banks’ reverential term for his grandfather) chose to only pass these stories down to men. And Banks repeats them with precision.

He begins, “Simon Dunbar was the son of a Thomas County slave master.” Dunbar was Banks’ fraternal great-great-great grandfather. His mixed ancestry was likely on his maternal side as well. Davis further shared that his grandmother, Hattie Jen McMath Davis, “an angel if God ever sent one,” says Banks, “had a father who was enslaved, but upon receiving his emancipation, was given 100 acres of land according to the family. Something odd for a person unless there was a blood tie.” He smiles knowingly. Eventually, the Georgia land would be passed down to Mr. Davis and his sister, along with a message to Davis that he would do great things.

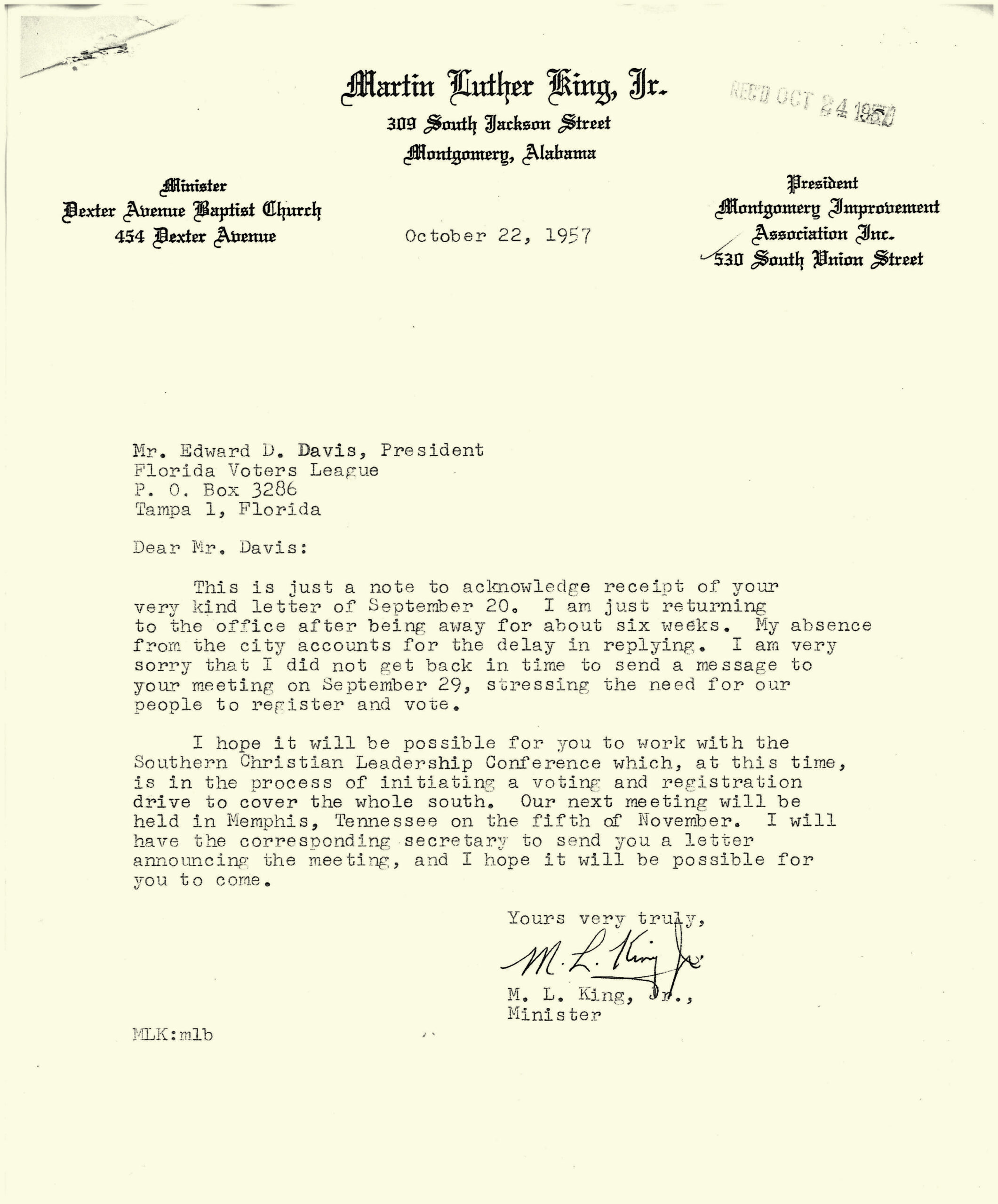

Indeed, Davis did great things. Banks smiles wide when he tells the story of how Davis—long before the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. marched and Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat—fought for civil rights. It is hard to miss the adoration Banks has for Davis. He lists Davis’ accomplishments one-by-one. Firstly, Davis started the Florida Voters League in 1935, a nonpartisan organization created to educate and register Black voters. He returned to again serve as the league’s president in 1957. Banks says the league was so strong it swayed the 1948 presidential election of Harry Truman and Leroy Collins’ Florida gubernatorial race in 1956. “Back then, if candidates were racist, they lost the Black vote,” says Banks.

To Banks’ surprise and delight, his grandfather went on to publish a memoir, A Half Century of Struggle for Freedom in Florida, in 1981. Banks attended the book signing, taking away even more knowledge. Decades of further research would pass before Banks would honor Mr. Davis’ life in print. A King Mighty in Battle by Banks was published in February 2020.

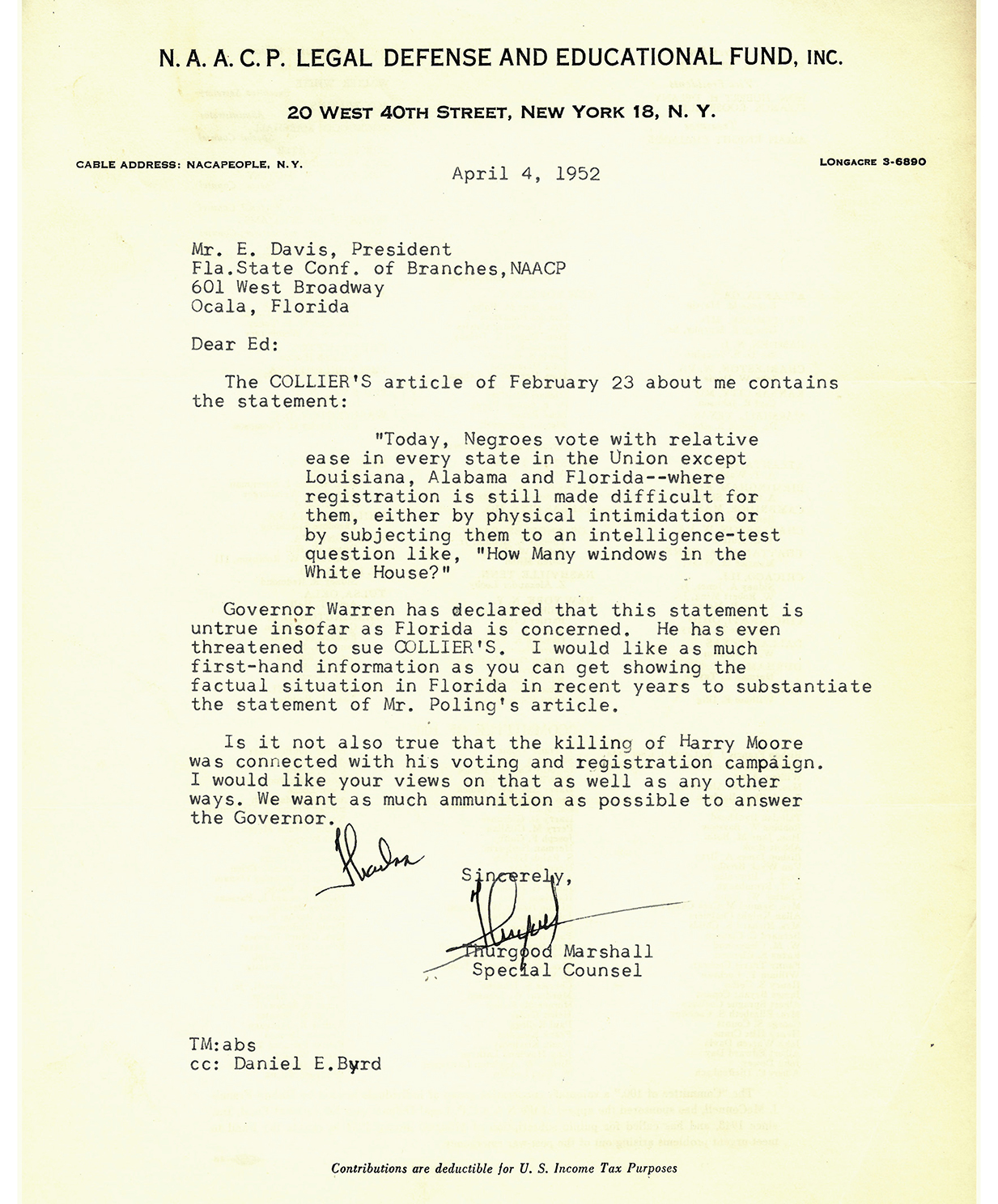

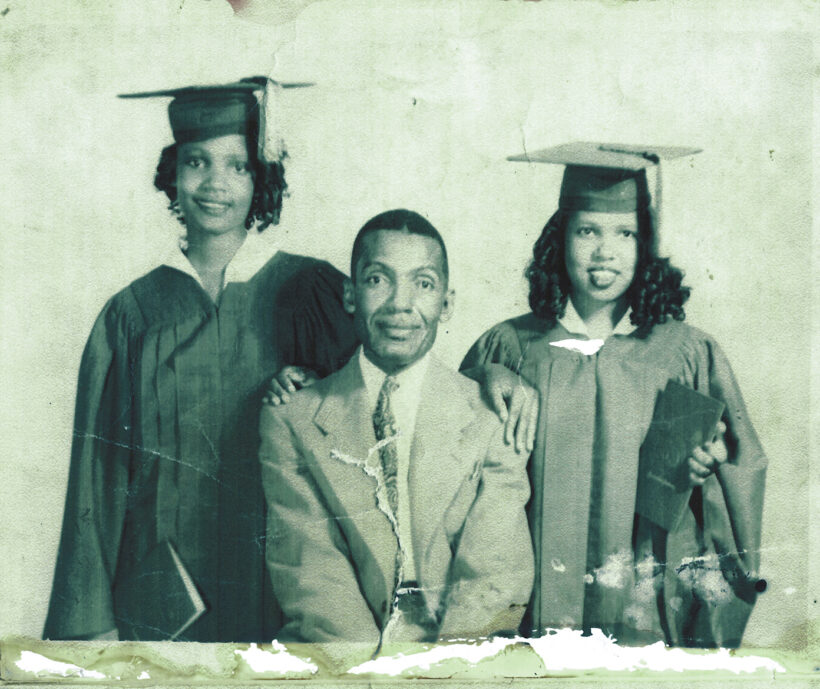

“Every Black teacher and student owe a debt of thanks for these men,” says Banks. He refers to Mr. Davis and his colleague, Harry T. Moore, another civil rights icon. Davis presided over the Florida State Teachers Association at the time. According to Banks, the two men joined forces in the late 1930s to fight for equal pay for Black teachers and equal facilities for Black students. They would receive strategic insight from NAACP attorney Thurgood Marshall.

Consequently, the backlash was swift. In 1942, Davis, then principal of Howard Academy (now the Howard Academy Community Center, or HACC) was fired by the superintendent. Davis would leave education, return to Tampa and eventually build a profitable insurance business with offices in three states before retiring to Orlando.

Davis kept roots in Ocala, though. He cared for his family. “He loved his daughter,” Banks explains of his mother, Alice Marie Davis Banks. She was a teacher at Howard Academy, years after her father lost his principalship. Banks remembers that in the evenings, after teaching all day, she worked at the laundromat or Shell gas station that Mr. Davis owned. The businesses, a mile from the school, stood across from Covenant Missionary Baptist Church. However, when Banks was 10, Davis told him the businesses were going to be “displaced.”

“Mr. Davis explained that the city was going to build a bridge,” he says.

Banks recalls trying to visualize the words from his grandfather and replying childishly, “I don’t see it.”

He chuckles for a moment—the audacity of change. Banks did not see it then, but soon he would see the bridge (the railroad overpass that brings traffic into downtown Ocala on State Road 40) he believes was built to separate the Black community from the rest of the city.

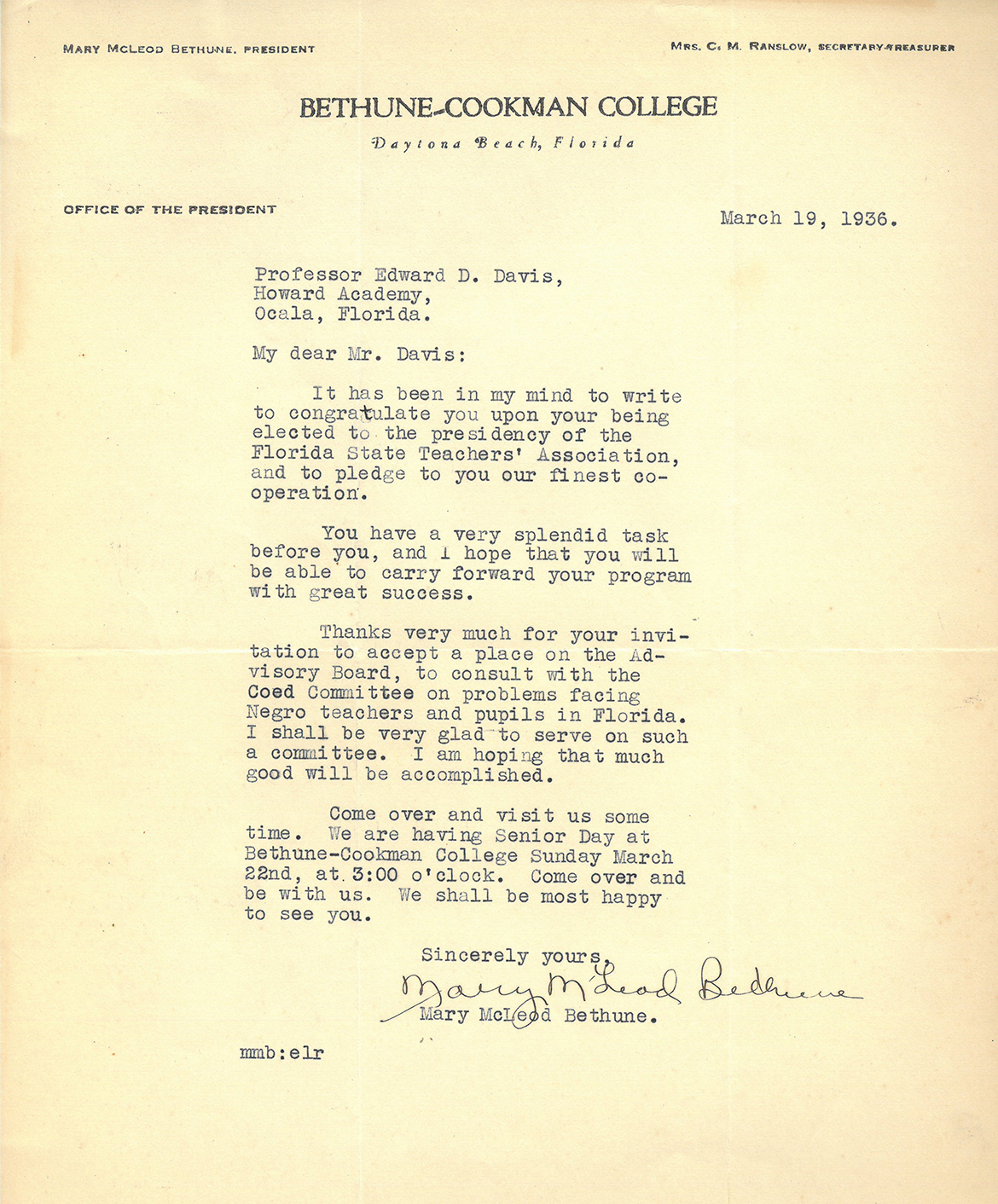

After publishing a second biography in August of 2022, Letters to Mr. Davis: from Thurgood Marshall, Mary McLeod Bethune, Martin Luther King, Jr., and more, Banks shared a snippet during a Sunday school class in January at Fort King Presbyterian Church. Margaret Spontak was in the audience. She knew the community. Her parents were local teachers. Yet Davis’ name was unfamiliar.

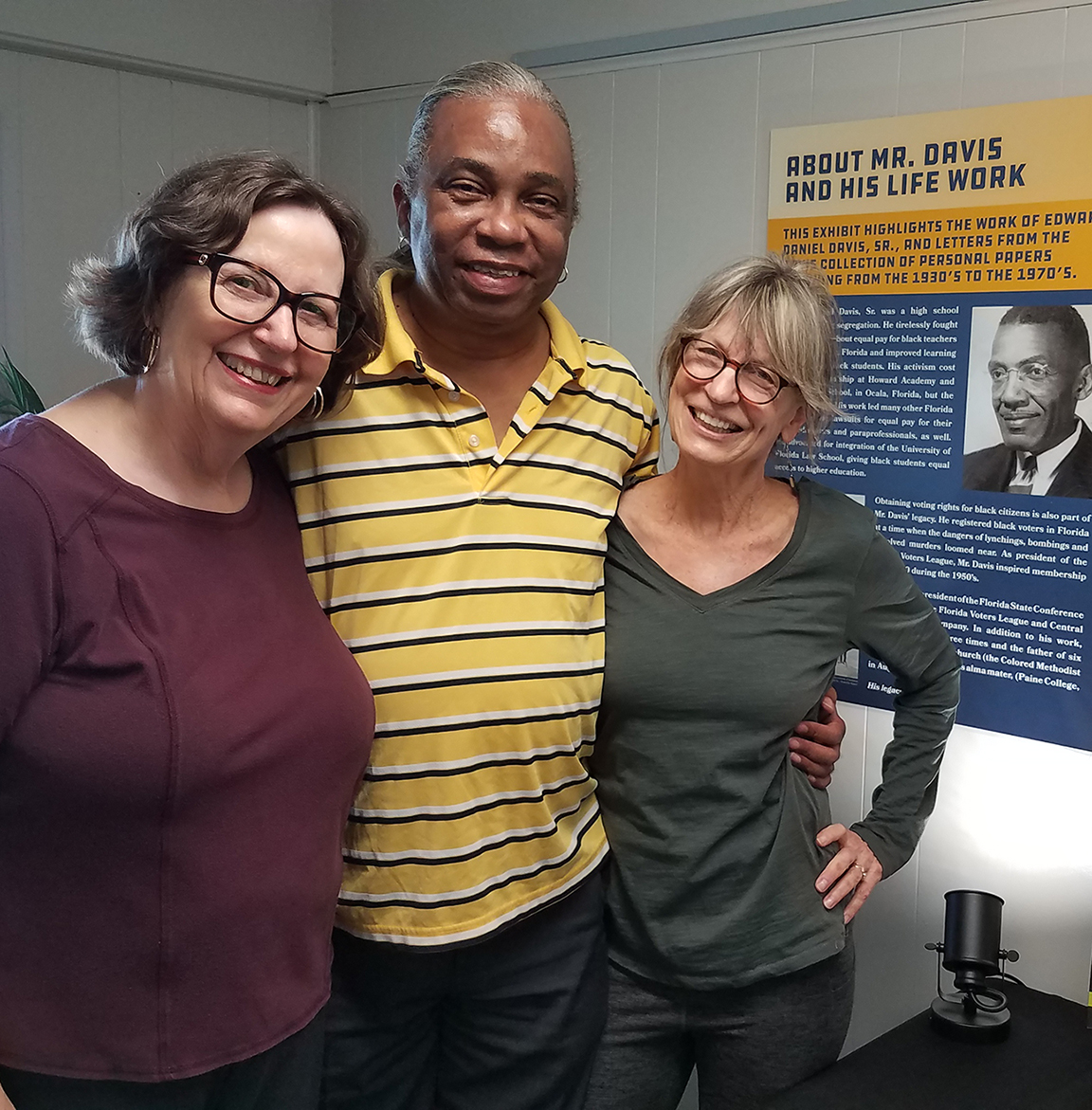

“You need to do an exhibit,” recalls Spontak of her conversation with Banks immediately afterward. On February 19th, nearly a month later, the church’s Hope House hosted the Edward Davis exhibition and book signing. Letters is an extraordinary collection of documents, which were bequeathed “in perfect order” by Sims to Banks. The letters that chronicle the civil rights movement in the South were enlarged and displayed around the room. Copies of Davis’ memoir and Banks’ books on Davis centered the exhibit, which ran for two months.

Other notable artifacts, too many to list, on Davis, are located throughout Florida. Several are attributed to Banks’ persistence. After a couple of rejections and years of research, in 2015, under Governor Rick Scott, Davis finally received a posthumous induction into the Florida Civil Rights Hall of Fame. Later, Banks petitioned the city of Ocala to dedicate the road running along Howard Academy to Davis. The council unanimously approved.

“A street he used to get to work now bears his name,” says Banks.

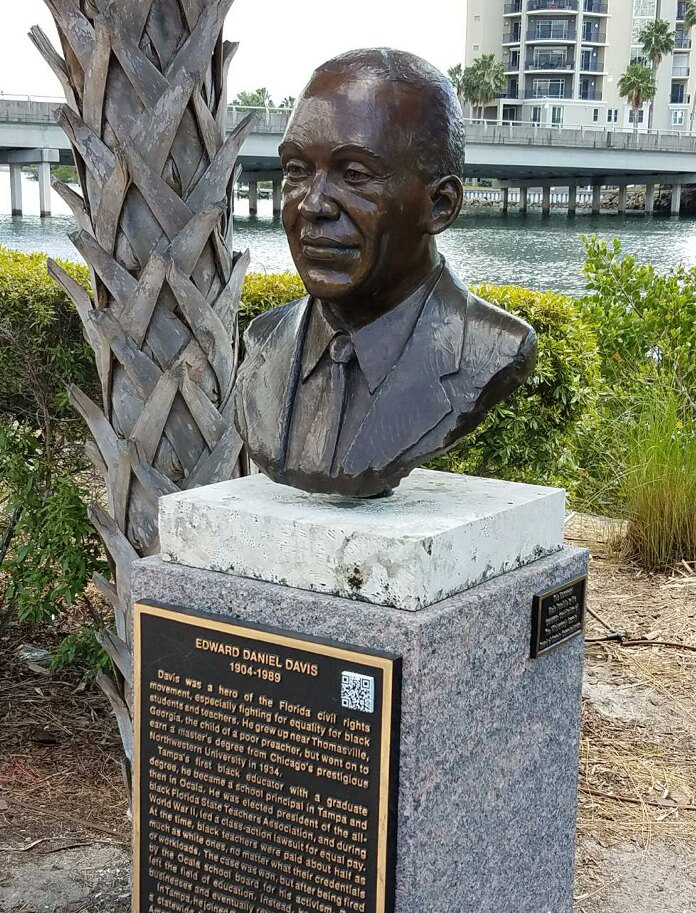

Davis is celebrated outside of Ocala as well. The Florida legislation named a portion of U.S. 441 and Colonial Drive in Orlando after him. And, in December 2016, a bronze bust of a younger Davis was unveiled, compliments of the Hillsborough County Commissioners. It sits on a marble stand at the Tampa Riverwalk Historical Monument Trail with the Hillsborough River as its backdrop.

Banks had hopes of Davis’ story becoming a part of the University of Florida’s Smather’s Library in connection to Davis’ work to admit Virgil Hawkins into the university’s law school. Reuben Buchanan and Banks had started the process before Buchanan’s untimely death.

The College of Central Florida, closer to home, is allowing Davis’ story to thrive. Banks is currently teaching Senior Learners using Letters as the text.

Banks is determined to preserve Davis’ place in Florida history while taking up his grandfather’s socio-political causes.

“It has been 80 years since Mr. Davis started this,” he offers. “We can see things change. But then there is another mountain.”

There are even more letters and documents on Davis still in bins. Some are too personal to share. But what Banks has traced genealogically thus far is now a legacy he sincerely shares with all. His generosity extends to anyone longing to discover their roots.

In mid-April, the Fort King Presbyterian Church donated the $3,000 exhibit to the HACC under Davida Randolph’s direction. Its arrival is a full circle stop on the street bearing Davis’ name in the community rich in Bank’s praiseworthy remembrances of his ancestors. Davis’ story has found a forever home. OS