Stone tools can tell us a lot about our ancestors or leave us guessing about why the implements were crafted.

Having worked in museums full of ancient things for a good bit of my career, I’ve developed a fascination with prehistoric stone tools. They are intriguing and diverse objects and can be both mysterious and informative about the people who made them. Stone tools may be works of art or simply crude but effective implements.

In the absence of metal, stone is among the hardest materials found in nature. Since the first metals (save some prehistoric Native copper acquired through trade) did not arrive in Florida until 1513, stone was used for thousands of years to make a variety of tools that were necessary for survival.

The stone most often used is referred to as flint or chert. Flint tends to be denser and is found in chalk deposits while chert is of lesser quality and occurs in limestone. Both materials are very hard and sharp when fractured and the names are basically interchangeable. If one needs a sharp tool in the wild, this is the material you need.

The stone most often used is referred to as flint or chert. Flint tends to be denser and is found in chalk deposits while chert is of lesser quality and occurs in limestone. Both materials are very hard and sharp when fractured and the names are basically interchangeable. If one needs a sharp tool in the wild, this is the material you need.

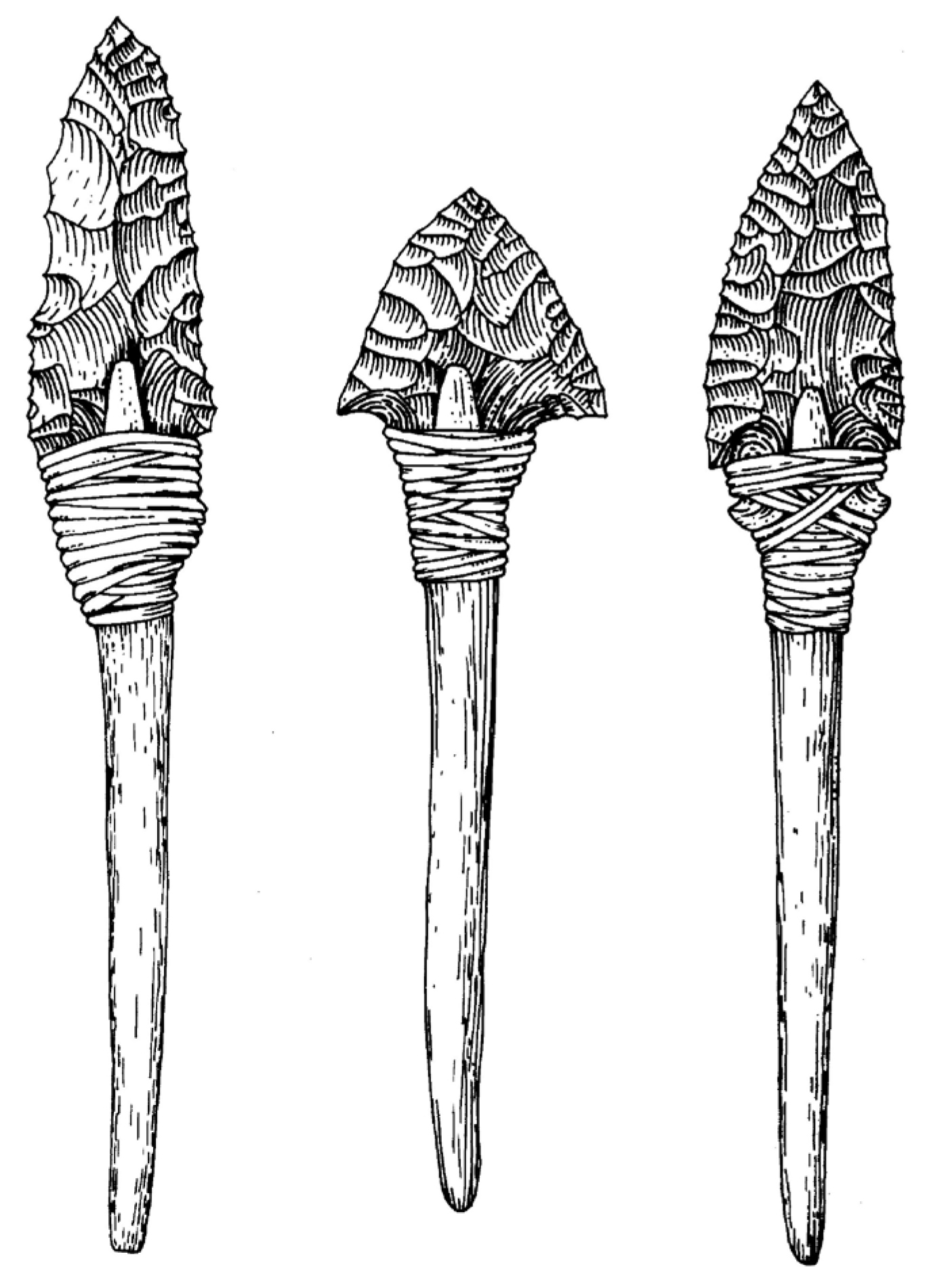

Most everyone calls the stone points arrowheads. Very few of them, however, were actually used to tip arrows. Larger points were more likely used as knives or to tip darts launched with a spear throwing stick or atlatl. True arrowheads are small, sharp triangular blades made for hunting or warfare. These points don’t appear in the archaeological record until about 2,000 years ago (which is also a clue for when the bow and arrow arrived in the Southeast). Since we believe people have lived here for at least 14,000 years and likely much longer, one can understand why true arrow points are on the rare side.

Dart and spear points were just a small part of the ancient toolkit. The majority of stone implements used by ancient Floridians were used to chop and carve wood, shred plant fibers to create cordage and basketry, cut up food for the cooking pot and process hides to create leather. These were the everyday tasks necessary to survive. While we like to imagine the hunter stalking big game, the reality is that most of these objects were used by people to feed, clothe and create shelter for themselves.

Sometimes we find a stone tool and its use is a complete mystery. In these cases, we rely on comparisons to cultures who used similar tools in historic times and detective-like analyses to find clues about how they were used. Microscopic wear on the working edges can yield clues about the type of material the implement was used to work on. Animal hides, wood and other materials all leave different wear patterns on even the hardest of stone.

Sometimes we find a stone tool and its use is a complete mystery. In these cases, we rely on comparisons to cultures who used similar tools in historic times and detective-like analyses to find clues about how they were used. Microscopic wear on the working edges can yield clues about the type of material the implement was used to work on. Animal hides, wood and other materials all leave different wear patterns on even the hardest of stone.

Evidence of plant-based or hide glues is sometimes present and helps us understand how stone tools were attached to handles. In some cases, tiny amounts of blood residue can be detected and analyzed to indicate what type of animal the tool was used to hunt or butcher. The oldest points have even been found in association with the fossils of extinct Ice Age animals.

Archaeologists are now able to source chert from various locations and recreate ancient trade routes. Stone that occurs in one region may have been traded and later found miles away in another region. All these clues help us understand more about long-forgotten technologies and trade routes.

Stone tool making, also known as flint knapping, is now a unique art form. Expert flint knappers recreate ancient tool forms and help us to better understand how the tools were made and used. The tools often are works of art, such as a beautifully made point made from colorful translucent chert. To me, what is most interesting is how they tell the stories of the past; the stories of people who lived thousands of years ago and never recorded their own history. The story of their past is told in stone.

You can see flint knappers at work—as well as shell carvers, potters, hide tanners, bow makers, dugout canoe carvers and other specialists in native skills—during the Silver River Knap-In Prehistoric Arts Festival on February 17th and 18th at Silver Springs State Park. For details, visit silverrivermuseum.com/silver-river-knap-in OS

Scott Mitchell is a field archaeologist, scientific illustrator and director of the Silver River Museum & Environmental Education Center at 1445 NE 58th Avenue, inside the Silver River State Park. Museum hours are 10am to 4pm Saturday and Sunday. To learn more, go to silverrivermuseum.com.