Leading dancers during the ceremonial grand entrance at the recent Leesburg Powwow are (from left) David Smith, Katherine “Raven” Stanley, and Herb “Buffalo Dancer” Sheppherd.

Apache, Chickasaw, Sioux, Dakota, Choctaw, Inca, Seneca, Creek, and Seminole—the Intertribal Cultural Arts Society’s roster is as diverse as any organization can get. Two hundred years ago, the tribes could have been mortal enemies, but current members bond over campfires and ceremonies that are steeped in tradition and heritage.

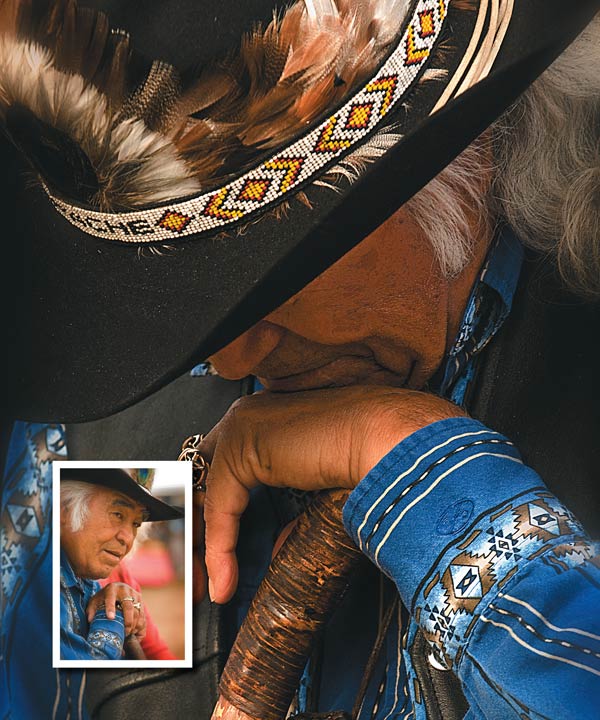

“At any given time, you can have 50 Indian nations represented,” explains Tom Lipps who organizes annual powwows in Leesburg for the society. “You never know who is going to show up.”

Nine-year-old Dakota Withers of Ft. McCoy has earned his Native American regalia by learning the tribal dances from his Lipan Apache grandfather.

Members come from all over the region to reconnect with their roots, once deeply buried in a white man’s world. After the turn of the 20th century, many areas outlawed teaching Native American culture. Young children were discouraged from learning the language of their forefathers, and tribal dances and ceremonies were forbidden. Traditions were quietly spoken about in some homes and completely denied in others.

“We were a hidden culture,” says Lipps. “We are trying to keep our heritage alive and educate people, especially young people, about the roles that Indians had in our country.”

A Lake County native, Lipps and his wife, Tina, organize and work the powwows that are held off Highway 27 just south of Main Street in Leesburg. They say their son Chris plans to come home from the Air Force and continue the powwow ceremonies that they have worked hard to build.

Lipps isn’t shy about describing himself as an “Indian,” rather than today’s politically correct “Native American.”

Ernie Lara, of Apache descent, is a member of the Family Drum Singers. The group performs at powwows around Florida.

“It was good enough for Geronimo and Red Cloud—they called themselves Indians,” he says with a smile. “It’s good enough for me.”

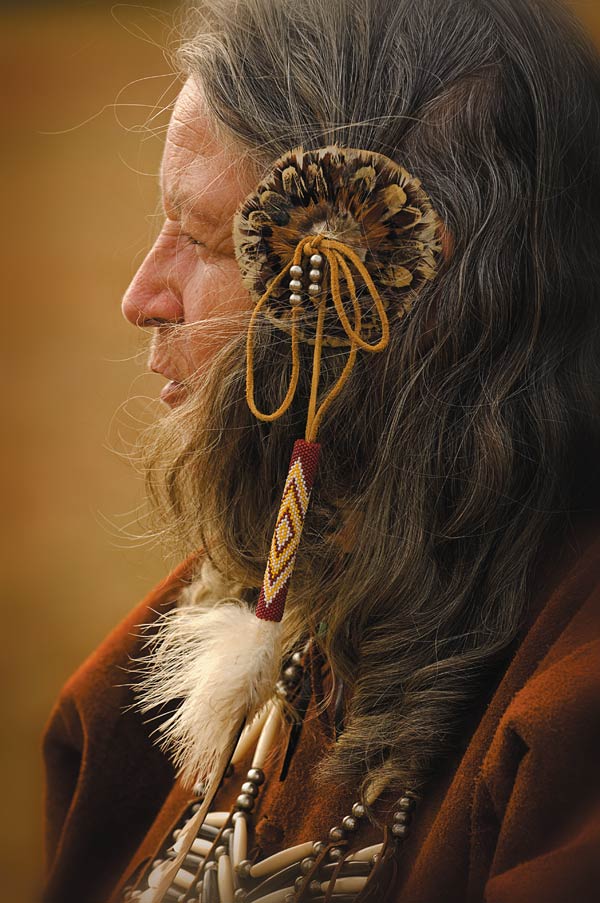

Dave Whitewolf Trezak of Ocala has been “doing powwows” most of his life. His mother was a Sioux from North Dakota, and he has traveled around the country as an entertainer, showman, and master of ceremonies for powwows. He opened the Leesburg event with greetings from several tribal languages: “gin-tom-o” from the Seminoles, “es-tango” from the Creeks, “Sa-go” from the Mohawks, and “yah-ta-hay” from the Navaho.

“All the native nations have different languages—575 languages are currently being used today,” he explains. “There used to be many, many more.”

With so many different tribes represented, it’s amazing that the drummers and singers can find a common ground. They do, however, by using “vocaboles.” Trezak says these are common sounds that allow the tribes to sing together without knowing each others’ languages.

-DSC_4891[1].jpg)

Herb “Buffalo Dancer” Sheppherd served as the head dancer at both the Leesburg and Webster powwows. The head dancer coordinates all of the others and makes sure everyone is in step.

The tribal dances performed during the powwow are “nothing like you see on TV.” Trezak carefully explains each dance to attendees who may not understand the symbolism and spirituality that the performers are trying to convey.

It was the spirituality of Native American traditions that touched Mike Whitewolf Serio, who grew up with an Italian father and a Cherokee mother. During local powwows, he serves as the arena director helping the dancers to uphold many of the rituals that they consider sacred before they enter the ceremonial area.

“The powwow is like a church fellowship to me,” Serio says. “Working as the arena director has been an opportunity to give back to my culture.”

Molly “Two-Braids” Stevenson is a descendent of the Flat Head Tribe. She is known throughout the region for her beadwork and authentic recreations of Native American regalia.

Serio explains that a large part of arena protocol includes “smudging,” a ceremonial form of cleansing where white sage is brushed on the dancers with feathers. As the dancers are smudged, they place their hands on their chests to signify purification of the heart. Hands to the mouth symbolize pure words. The smudging is considered so sacred that photographs are not allowed of the ritual.

A resident of Citrus County, Serio says that traditions such as smudging have been integrated into his everyday life. He also teaches the Cherokee language at the Crystal River library and currently has eight students.

“You have powwow Indians, just like you have Sunday-only Christians,” he says. “But many of us live it every day.”

Before the traditional tribal dances get underway, the event begins with a tribute to all military veterans, including those in the audience who are invited into the arena for the “hug line,” a tradition that began with soldiers returning from Vietnam more than 30 years ago.

“Our people have always honored veterans, even during the Vietnam War,” says Dave Reese of Ocala, who started the Florida Chapter of the Veterans Honor Society that is active at every Florida powwow. “Our mission is to thank all vets for their service.”

Members wear red sashes so that they recognize each other as part of the elite Honor Society. They also support the veterans home at Fort McCoy and veterans hospitals.

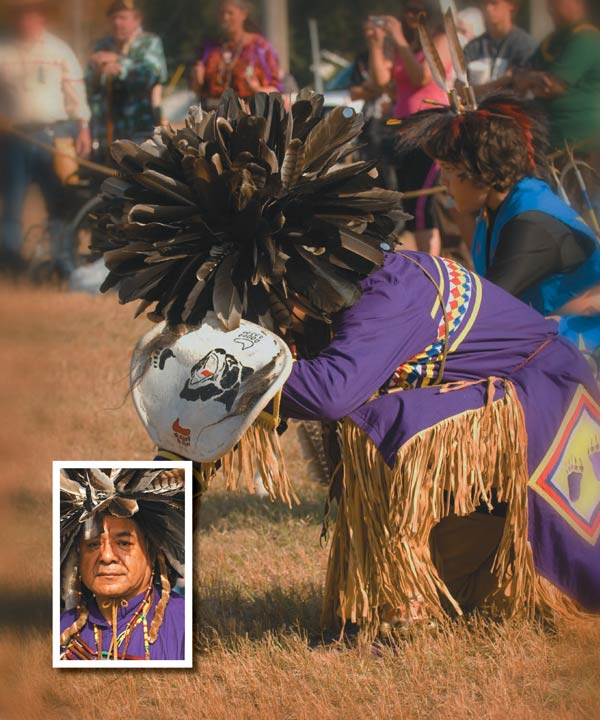

Thomas “Washa Mata or Little Bear” Zermeno performs the Sneak–Up Dance. The dance illustrates how the warriors hunt their prey.

Once the veterans leave the arena, the traditional dances get underway and can go for hours. The dancers’ regalia—not costumes—can be elaborate or simple and is often handed down through generations.

Thomas Zermeno is a Lipan Apache, originally from Corpus Christi, Texas, who now lives in Titusville. He learned the tribal dances when he was about eight years old, but he was not allowed to dress in regalia.

“Regalia has to be earned,” he says from under his expansive headdress of eagle and hawk feathers.

Now 60, Thomas dances in 10 to 15 powwows a year with his young grandsons Dakota Withers and Austin Nix, both of Fort McCoy. He is proud that 9-year-old Dakota is well on his way to earning his own regalia by learning tribal dances and culture.

“I bring them so they can see the younger dancers,” he says with a laugh. “I can’t move like that any more.”

A safety expert at Cape Canaveral, Thomas regularly attends powwows in Mount Dora, which are held at Renninger’s Twin Markets on Highway 441.

“This,” he explains, “is my life after work.”

Want to know more?

-Howard,-Trader-3-DSC_4268[1].jpg)

Powwows are more than just entertainment; they often have spiritual or patriotic significance for the Native American dancers. Here are a few things you should know when you attend:

1. Stand and remove your hat when the American flag is raised or lowered.

2. Take a lawn chair with you. Most powwows do not have public seating or enough seating for everyone. The benches around the arena are reserved for the dancers.

3. Support the powwow by buying a raffle ticket or making a donation. Powwows are usually non-profit, and they depend upon donations and raffles to cover event expenses.

4. Respect the traditions. Certain types of sacred Native American items or regalia should be worn only by those qualified to do so.

5. Ask the dancers if you may take their pictures. Photos of some ceremonies, such as smudging, are not allowed.

6. If you are uncertain about protocol or etiquette, ask the master of ceremonies, the arena director, or the head singer. They will be glad to answer your questions.

7. All powwows are different. If you visit several, be respectful of the uniqueness in each area.

Source: powwows.com