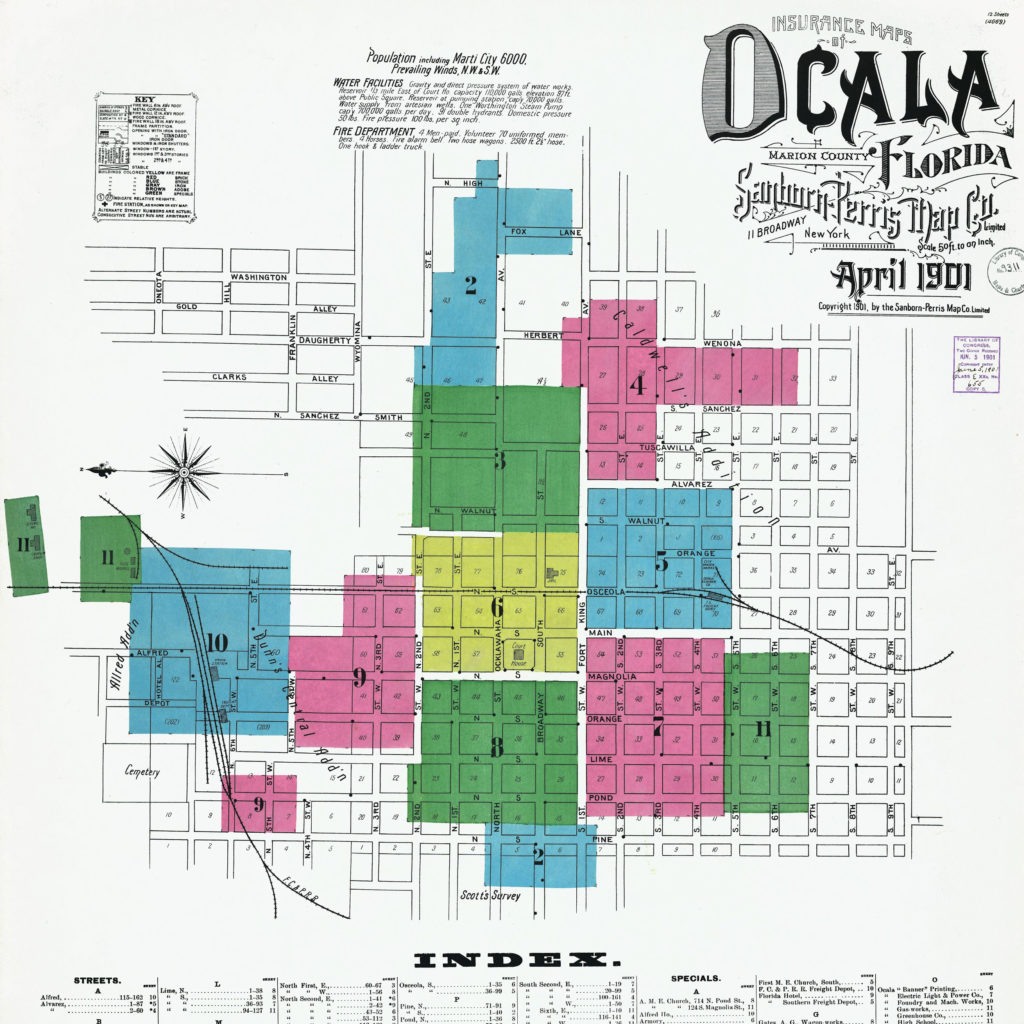

Ocala! Horse Capital of the World! That’s what many Ocala boosters proclaim today. But if big economic development plans in late 19th-century Ocala had panned out, today’s mantra could instead be: Martí City! Cigar Capital of the World!

In the 1880s, many Southerners rejected the agrarian economy of the Old South, especially the slave-based plantation system. Instead, they campaigned for a modern, industrial New South.

In the 1880s, many Southerners rejected the agrarian economy of the Old South, especially the slave-based plantation system. Instead, they campaigned for a modern, industrial New South.

In Ocala, many business people were promoting cigar rolling, an industry that Cuban immigrants had brought to our area with them. In fact, hopes were high, according to Florida historian L. Glenn Westfall, that Ocala would become “the next great cigar capital of Florida.”

Cuban Tradition Travels North

In 1889, cigar workers appeared in Ocala at the three-story Semi-Tropical Exposition Hall on West Broadway, which displayed a dazzling array of horticultural and agricultural products from across Florida and beyond. One of the exhibits, a Cuban village, highlighted Cubans crafting cigars. Locals called the village “Havana Town.”

During the next few years, the village grew into a prosperous cigar manufacturing district and Ocala’s West End received a more inspired name: Martí City.

Though it was an economic interest that motivated them, Ocala’s business class was paying homage to a famous revolutionary—José Martí, the Apostle of Cuban Independence.

Martí the Revolutionary

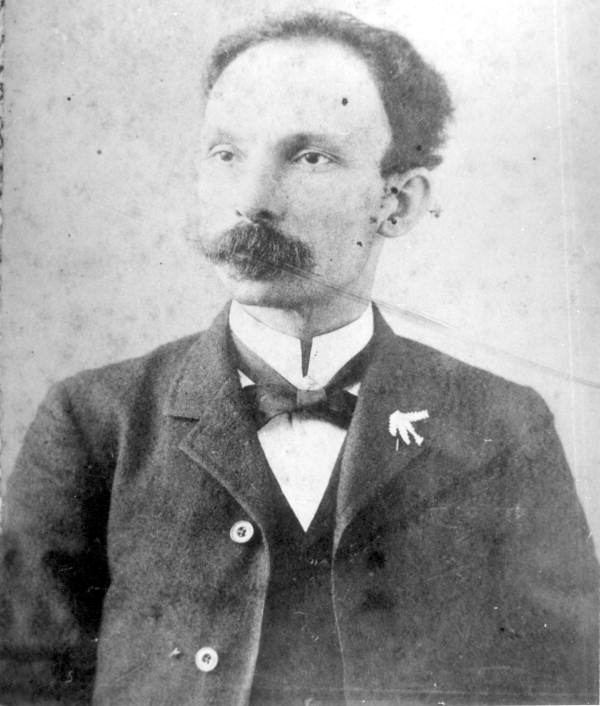

Martí may not be well known in many American households today, but he was once a popular and respected figure not only in Ocala, but across America and beyond. In 1895, U.S. Senator Wilkinson Call from Florida told his fellow lawmakers that Martí, “is second scarcely to any character in the pages of history.” Cubans everywhere still honor him like a saint.

Martí was born in Havana, Cuba in 1853, when Spain still ruled the island. Growing up there gave him an overt and lasting hatred of slavery, oppression and injustice. An early dissenter against Spanish tyranny, Martí landed in a Cuban jail while a teenager. Decades of exile came next. He attended university in Spain, taught, and worked as a journalist in Mexico, Guatemala, Venezuela and the United States. He was a political troublemaker wherever he went, making his views known in speeches, articles and books in Spanish and English. His targets were corrupt rulers and unjust political systems. Martí championed the oppressed and the downtrodden. Though he admired America’s embrace of individual freedoms, he was troubled by the country’s racism, materialism and imperialism.

Martí was born in Havana, Cuba in 1853, when Spain still ruled the island. Growing up there gave him an overt and lasting hatred of slavery, oppression and injustice. An early dissenter against Spanish tyranny, Martí landed in a Cuban jail while a teenager. Decades of exile came next. He attended university in Spain, taught, and worked as a journalist in Mexico, Guatemala, Venezuela and the United States. He was a political troublemaker wherever he went, making his views known in speeches, articles and books in Spanish and English. His targets were corrupt rulers and unjust political systems. Martí championed the oppressed and the downtrodden. Though he admired America’s embrace of individual freedoms, he was troubled by the country’s racism, materialism and imperialism.

By the late 1880s, the thin, mustached young man, who always wore black, had become one of Cuba’s leading firebrands. A master wordsmith, he implored Cubans everywhere to rise up together and overthrow Spanish rule and replace it with a new democratic society based on the ideals of justice and human dignity for all.

Martí was an intense, strong-willed, opinionated intellectual when he joined a group of Cuban patriots in New York planning to oust the Spanish. They gave him the task of raising money and inspiring support for the coming revolution.

High on his list of promising fundraising sites were cigar-rolling factories, notably those in Florida. During the mid-19th century, U.S. tariffs on imported cigars had crippled the Cuban cigar industry. Factory owners responded by exporting raw tobacco leaf to new factories in Florida, where Cuban workers began making cigars from scratch.

A Booming Business

Many of Ocala’s business leaders spurred the growth of this industry by luring workers from Ybor City in Tampa, Key West and elsewhere with promises of cheaper housing, steady work and gestures of hospitality. Tobacco farms popped up nearby to supply raw material. Merchants declared West Ocala would be a “Cuban only” section of town to prevent a repeat of conflicts at cigar plants in Key West between Spaniards and independence-minded Cubans.

For a while, it all worked. Martí City grew quickly as Cubans arrived by the hundreds. In 1892 the town incorporated and elected its own officials.

By 1896, the new suburb just west of downtown Ocala had 13 cigar factories plus a factory for making cigar boxes. Businesses with names like La Criolla Cigar Manufacturing and J. Vidal Cruz and Company became commonplace.

Soon another seven factories set up in Ocala.

No matter where they were located, Florida’s cigar factories followed the same design and layout, says Dr. James López, co-director of the Center for José Martí Studies Affiliate at the University of Tampa.  Everyday life in these workplaces also followed a unique script.

Everyday life in these workplaces also followed a unique script.

Cigar workers in Ocala didn’t suffer slavish conditions endured by many other Americans toiling in dangerous, low-paid jobs in textile mills, mines and factories. Instead, Florida’s cigar factories were also education, or self-improvement, centers. Each day, on raised platforms, “lectors” read to the artisans as they cut and rolled tobacco. In the morning, their reading material was Spanish language periodicals, ranging from mainstream to more radical publications. After lunch, workers heard great works of literature.

“The workers in Ocala and elsewhere were, in their own eyes, not laborers, but artisans,” says López. “They were mobile and would go where the work was. Many saw themselves as temporary workers in exile; a significant portion was interested in labor rights, and some were involved in the anarchist movement.”

“These tobacco people were a very special group of people,” says Pedro Roig, Executive Director of the Miami-based, Cuban Studies Institute. “When Martí arrived with his vocabulary, they could understand his words.”

Martí the Legend

Martí used soaring rhetoric to drum up support for Cuban independence. He encouraged a dispirited mix of Cuban exiles, rich and poor, white and Afro-Cuban, to unite. “Either the Republic is founded upon…everyone…,” he proclaimed, “or the Republic is not worth one of our mothers’ tears, or a single drop of our heroes’ blood.”

Above all, he had to raise money to pay for an invasion.

On July 15th, 1892, Martí first appeared in Ocala alongside a delegation of Cubans bent on revolution.

“Martí was given a triumphant reception by Martí City Cubans and Ocala Crackers,” writes Westfall. “It was to the advantage of the Ocala business community to support the revolutionary movement.”

Martí was pleased with the reception. He later praised the cigar workers who pledged to contribute “25 cents a week for the revolution for the independence of our fatherland Cuba.” He returned in October of that year and was treated like a rock star.

In 1895, the Cuban Revolution was underway. Martí, wishing to prove himself on the battlefield, arrived in Cuba and was killed in combat at Dos Rios on May 19th. He was only 42.

In death he achieved martyrdom, but it was not enough to lead the rebels to victory. Instead, their efforts were eclipsed by the United States in 1898, when the nation went to war with Spain and won. To the shock of Cubans, the Americans then turned Cuba into a near vassal state, a condition that lasted until Fidel Castro and his forces seized control of the island in 1959.

When Martí died, Martí City was in decline. A nationwide depression, along with competition from Tampa’s cigar industry, prompted the Ocala workers to pack their bags. A few cigar factories limped into the 1920s and then disappeared.

The lector tradition is also gone.

“My maternal grandfather, Wilfredo Rodriquez, was the last living lector in Florida,” López says of the man known as El Mejicanito, who read to factory workers from 1928-1931.

And Martí City? Historian Westfall says it became a ghost town.

Martí City’s Legacy

Not all the ghosts are forgotten. In 2010, Ocalan Catherine Wendell worked at the Seven Sisters Inn, an upscale B&B on historic Fort King Street. The house once belonged to Charles Rheinauer, an influential Ocala merchant who also served as president of the La Criolla Cigar Company and was a friend and benefactor of Martí.

Not all the ghosts are forgotten. In 2010, Ocalan Catherine Wendell worked at the Seven Sisters Inn, an upscale B&B on historic Fort King Street. The house once belonged to Charles Rheinauer, an influential Ocala merchant who also served as president of the La Criolla Cigar Company and was a friend and benefactor of Martí.

In 2010, something strange kept happening at the inn, Wendell recalls. “We would smell cigar smoke coming from the Paris Room, but nobody smoked there.”

One day, Wendell asked aloud, “Is that you, Mr. Rheinauer?”

A man’s disembodied voice, Wendell says, replied, “Yes.”

Only years later did she associate the smell of cigar smoke with Martí, who likely visited there.

Wendell now owns Ocala Ghost Walks & Historical Tours and tells the Martí story on her guided nocturnal tours.

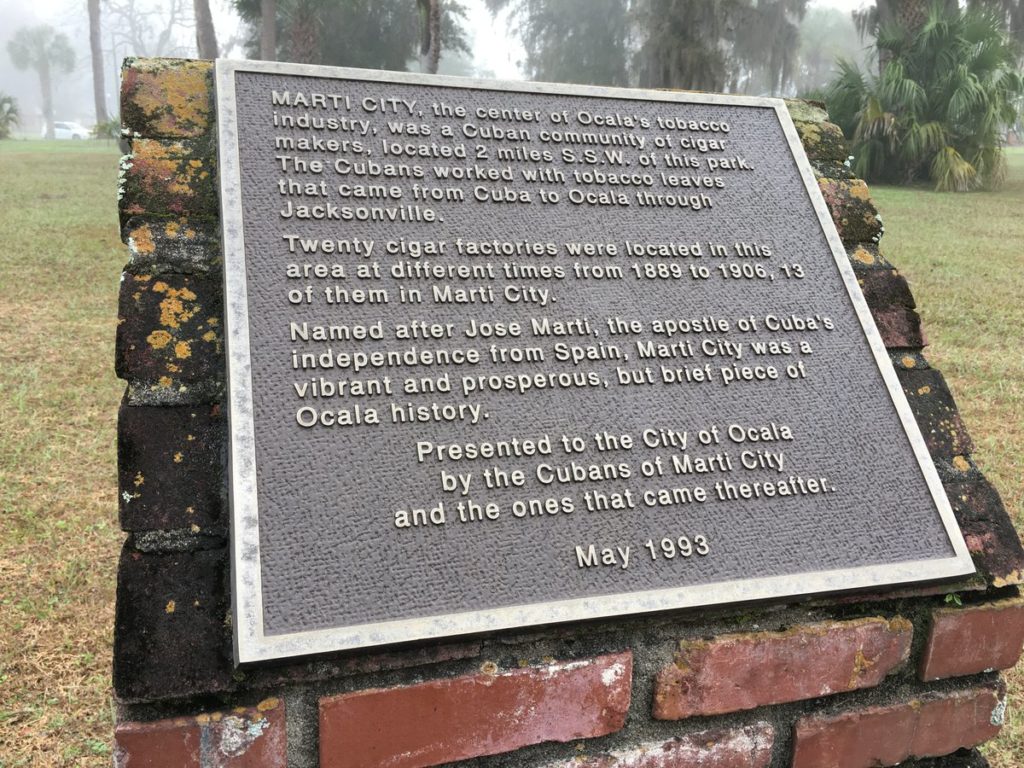

There’s also a more substantial reminder of Martí’s presence, thanks to Ocalan Maria Pares. In February of 1993, on behalf of Marion County’s Cuban citizens, she persuaded the Ocala City Council to erect a red-brick monument commemorating Martí City and José Martí. It is located in Tuscawilla Park.

For more on the subject, check out Dunn’s book Jose Martí: Cuba’s Greatest Hero on www.amazon.com