Meet some of the fascinating women who have helped shape our community through their passion, service and dedication.

Marion County’s Historic Midwives

Far longer than women have been having babies in sterile hospital rooms, women throughout history delivered their children at home. And long before the first hands to cradle their bundle of joy belonged to someone with the title Doctor, those skilled hands belonged to a caring midwife called “Aunt Mariah,” “Aunt Clarissa, “Mrs. Pie” or known simply as “Peggy.”

Although pregnant women and new mothers are under threat of myriad complications and risks to their physical and emotional well-being, historically male doctors and healers were forbidden to participate in or even to be present at the birth of a child.

According to the historic text The History of Medicine in the United States by Francis Randolph Packard, “The midwife occupied a most important post in the community in the early settlements of this country. It was deemed beneath the dignity of male physicians to act as obstetricians.”

The word midwife was formed from two old English words. The prefix “mid” had the meaning “together with.” And although it would seem natural to assume that “wife” refers to a “female spouse” in old English, it simply meant “woman” and therefore the word quite literally meant “with-woman” and grew to describe “a woman who is with another woman to assist her in giving birth.” As midwives have been practicing as long as women have been having babies, it did not historically refer to an individual with any specific training or certification.

In Florida, indigenous peoples had their own midwives, herbalists, healers and observed such birthing customs for more than 10,000 years before the first Europeans arrived on our shores.

At the time Florida became a state in 1845, midwifery laws in America were local and varied widely. Midwives in most states practiced without government control and the support they provided women extended well beyond labor and delivery.

“The midwife’s work was more than ‘catching babies,’ they were psychologists, dietitians, loan officers, sex therapists, prayer partners, marriage counselors and friends and sometimes relatives to the women that they served,” wrote Dennis Brown M.D. and Pamela A. Toussaint in their book Mama’s Little Baby.

“The midwife’s work was more than ‘catching babies,’ they were psychologists, dietitians, loan officers, sex therapists, prayer partners, marriage counselors and friends and sometimes relatives to the women that they served,” wrote Dennis Brown M.D. and Pamela A. Toussaint in their book Mama’s Little Baby.

According to an estimate from the Florida Department of Health, some 4,000 midwives were serving Florida families by 1930. Most were Black women, following the home birthing traditions handed down by their foremothers who were required to serve as midwives for both other Black woman and white women as well, during the period of slavery in the United States.

The term “granny-midwife” was widely used to describe these traditional Black midwives, who were well-respected by their community but were sadly also subject

to ridicule and suspicion when things went wrong with a home birth.

Florida passed the first state midwifery licensing law in 1931 in an attempt to control and regulate the practice of midwifery for the protection of both mothers and infants. The law authorized the State Board of Health to make regulations, including that practicing midwives be at least 21 years old, be able to read the newly created Manual for Midwives and be able to fill out birth certificates. It also required midwives to possess a diploma from a school for midwives and become licensed by the State Board of Health. In 1931, approximately 1,400 midwives (35 percent of the midwives practicing at that time) received their licenses.

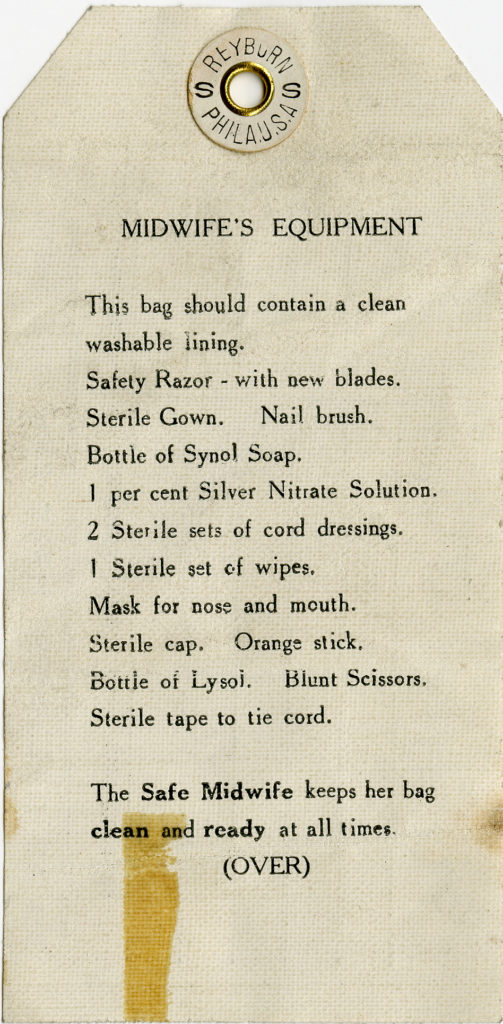

Florida began offering classes at the Midwife Institute established at Florida A&M University in Tallahassee, but also held training sessions in cities including Tampa and St. Augustine. Classes focused on such topics as care of the mother and the newborn, basic principles of hygiene, how to sterilize equipment and what supplies and equipment to pack in their “birth bag.” Attached to that bag was a tag that listed the items that should always be inside, including sharpened razors, sanitary solution, linens and bandages. The tag included the advice that “The Safe Midwife keeps her bag clean and ready at all times.”

Although many offered their services for free or for a nominal fee, often bartering or trading depending on what the family could afford, and were routinely paid with canned goods, produce and livestock, the midwives were expected to attend births whenever summoned—often at all hours of the night and for as many hours or days as the mother’s labor lasted. Beyond births, they served their community in a variety of ways that included providing medical supplies, clothing and other forms of assistance to families in need.

During the course of her lifetime, the typical midwife delivered, on average, upwards of 1,000 babies, both white and Black. Yet, despite the midwives’ contributions to the growth of all those family trees, their names are largely lost to history.

A rare portrait of a group of Marion County midwives at the Midwife Institute in St. Augustine from 1934 is included in the State Library and Archives of Florida collection. In the photo, 23 women pose with their instructors, beaming with pride and holding their “birth bags.” While the names of those particular women are not included, their inspiring legacy is preserved for all time.

According to The Struggle for Survival: A Partial History of the Negroes of Marion County, 1865 to 1976, published by the Black Historical Organization of Marion County, one Black Marion County midwife who attended to local women was a slave known only as Peggy. Born in 1745, the midwife, house servant and field hand was last recorded on the 1870 census at 125 years old.

According to The Struggle for Survival: A Partial History of the Negroes of Marion County, 1865 to 1976, published by the Black Historical Organization of Marion County, one Black Marion County midwife who attended to local women was a slave known only as Peggy. Born in 1745, the midwife, house servant and field hand was last recorded on the 1870 census at 125 years old.

“She’d lived through the French and Indian War, the Revolutionary War, the War of 1812 and the Civil War. Sixteen presidents had come and gone, and lands she lived in had changed hands between three countries,” Rob Brannan wrote of this inspiring woman in an article for the Free Press, after reading Peggy’s entry in The Struggle for Survival. “But while Peggy probably worked until the day of her death, it’s hard to imagine the pride she must of felt in her final days.”

Also thanks to the organization’s book, we know that Mrs. Ellen Sparks White worked as a midwife in West Ocala for many years alongside Dr. Nathaniel Hawthorne Jones—a highly-respected physician and the first Black doctor to become a staff physician at Munroe Memorial Hospital.

Ernest Wess, White’s great-grandson, has talked to many people over the years who remember births taking place at his family’s home.

“They’d say, ‘Yes, I know Miss Ellen. My mother had her baby over there.’ She delivered a lot of babies for a lot of people back then.”

Like so many other midwives, White’s compassion extended far beyond the back bedroom where she delivered babies.

“She was the one person that, if you came to her house and you were hungry, she would feed you,” Wess said of his great-grandmother. “That’s just the way she was. We were proud of her.”

Angelia Vernon Menchan says White brought her into the world. She commented recently when local author Cynthia Graham asked residents to share memories of local midwives on Facebook.

“She delivered me,” Menchan declared.

Another beloved midwife mentioned in the Black historical organization’s book was known as “Aunt Clarissa” Hill. Bea Mims Shepherd of Anthony recalled Hill, who had 12 children of her own, as “born in 1854, the daughter of a slave woman.”

““Her eyes were blue, her skin was light and her heart was of gold,” Shepherd wrote. She stayed with my mother when I was born in 1905.”

This was a common occurrence among midwives. In fact, one local we spoke with explained that, after assisting with a birth on an uncharacteristically bitter evening, the midwife who was attending to mother and child climbed into bed with them and spent the night, to shield them from the cold and ensure they were protected from the harsh weather.

This was a common occurrence among midwives. In fact, one local we spoke with explained that, after assisting with a birth on an uncharacteristically bitter evening, the midwife who was attending to mother and child climbed into bed with them and spent the night, to shield them from the cold and ensure they were protected from the harsh weather.

Locals also recall Mariah Floyd, known as “Aunt” Mariah, who provided midwife services in the Flemington/Shiloh/Brushlot area in northwest Marion County from the late 1800s through the early 1920s.

Sisters Nancy and Anabelle Leitner, who live on a pioneer farm in Shiloh, explained that Floyd was called to their family home when their father and his twin sister were born and also for subsequent births in the family.

Kathryn Crowell-Grate of Ocala shared her memories of other midwives on Graham’s post as well, stating that she herself had been delivered by Marcey Riley-Brown, known to many simply as “Mrs. Pie,” who also worked with Dr. Jones.

“She was the midwife who took care of Orange Lake, Reddick, Citra, Martin, etc.” she recalled. “There was also another midwife named Mrs. Bennie Bee. She delivered many babies back in the day.”

Another interesting entry in The Struggle for Survival came from Samuel J. Aldrich and details the close relationships that developed between white and Black neighbors in the Black community of Butlersville in northwest Marion County that was created following the Civil War. He specifically mentioned a white midwife by the name of Mrs. Hutcheons, who “served as a midwife to Blacks and whites in the community.”

In more modern times, certified nurse midwife Barbara Bigby helped deliver more babies than she kept count of through her work with the Midwives of Ocala, from 1998 until she retired in 2016.

Bigby was trained as a registered nurse (RN) and then certified nurse midwife (CNM) in Jamaica. She came to the U.S. in 1980 and was working as an RN in a labor and delivery unit and was “able to go to midwifery school for recertification for foreign-born nurses to practice in the U.S.”

The Midwives of Ocala were based at Munroe Regional Medical Center and she was the only Black midwife on the staff of eight. She says they were contracted through the health department “to help low-income women. A lot of our patients were Black, but not the majority. They were lower-income white, Hispanic…

“It was rewarding to help with their care and not just delivery,” she offers, “to guide them through their pregnancy, which could include diet, exercise, other healthcare needed through their reproductive years.”

She says benefits of having a midwife include “more intimate care, more time with the patient, teaching them and listening to their concerns.”

The evolving role of the midwife has long been one of nurturing care, of hope and health and answering a powerful call. Their dedication and commitment have helped define our community, uplifted and empowered women, positively impacted the social health of the family structure and helped advance maternity care. The midwife’s work was always more than catching babies.

The Marion County Public Library and the College of Central Florida Library have reference copies of The Struggle for Survival. The CF Library also has a digital copy that may be viewed under controlled digital lending guidelines. For more information, contact them by emailing library@cf.edu or call (352) 873-5805 for more information.

Star Turn

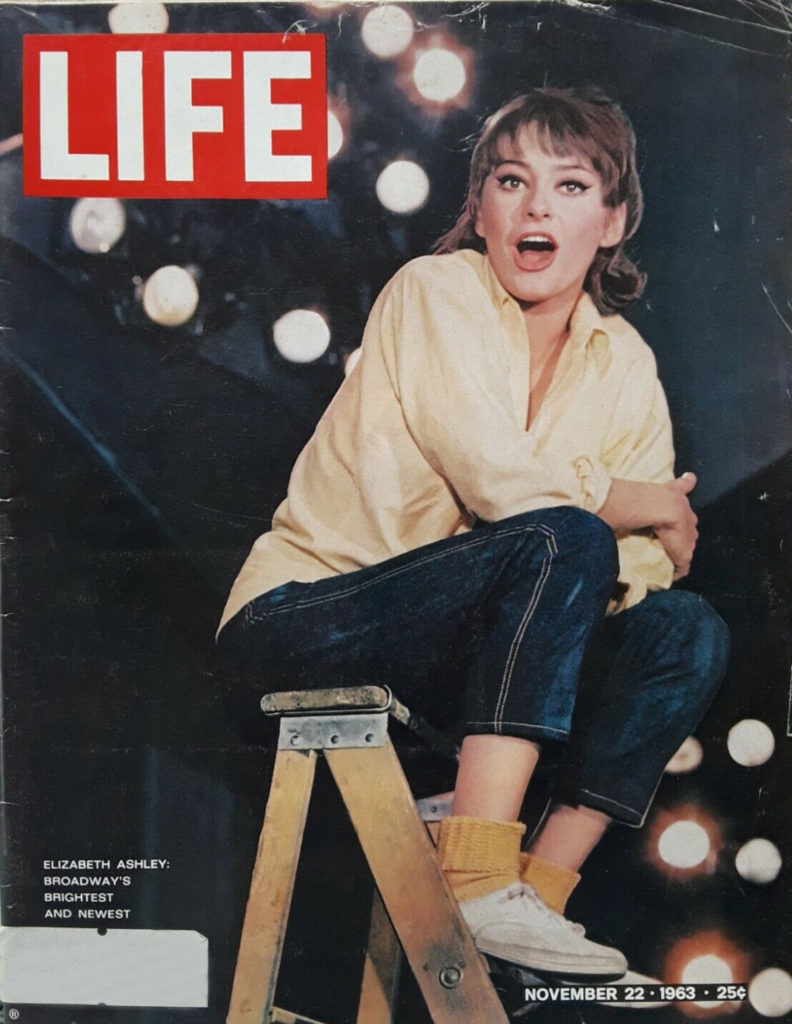

Elizabeth Ashley attained the status of one of the most acclaimed actresses of her generation, appearing in films, on TV and on Broadway opposite such leading men as Robert Redford and Burt Reynolds, working as a muse to the legendary writer Tennessee Williams and even appearing on the cover of LIFE Magazine. She has been nominated for many awards during the course of her career and won a Tony for Best Featured Actress in a Play for Take Her, She’s Mine.

Ashley was born Elizabeth Ann Cole in Ocala, to mother Lucille and music teacher father Arthur Kingman Cole. But, following her parents’ split, she and her mother relocated to Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

Ashley was born Elizabeth Ann Cole in Ocala, to mother Lucille and music teacher father Arthur Kingman Cole. But, following her parents’ split, she and her mother relocated to Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

“As she liked to say, with a baby under one arm and a sewing machine under the other, she put three states between herself and that son of a bitch!” she recalls.

Beyond being regarded for her talent, Ashley was known for her husky voice, once described as the embodiment of “Southern Comfort and mint juleps infused with magnolias.” Indeed, she possessed the old-world aura of a true deep-south belle. These qualities, plus oft-admired legs, made her a standout in New York and Hollywood.

She quickly found success on the stage, making her Broadway debut opposite a young Robert Redford in his first role. The pair would later reunite on stage in 1963 in the world premiere of Neil Simon’s hit play Barefoot in the Park.

Her status as “Broadway’s brightest” was heralded when she landed on the cover of LIFE Magazine that same year.

She made her film debut in the “big-budget, pot boiler” The Carpetbaggers, which became one of 1964’s biggest hits, co-starring her future ex-husband George Peppard.

A close friendship with playwright Tennessee Williams led to perhaps the most satisfying role of her career as Maggie “the Cat” in the Broadway revival of Williams’ Cat on a Hot Tin Roof in 1974. In the original staging, Williams was convinced to edit out dialogue and themes that were not considered appropriate for the original 1950s audiences. The 1974 version was what Williams had originally intended and he worked closely with Ashley to reignite the classic tale. Critics heaped on the praise, as she electrified audiences, calling it a part “she was born to play.”

Ashley has taken breaks from acting over the years to do other things that fed her soul, explaining that while other actresses were plotting out their careers, “sitting in Sardi’s or the Polo Lounge in Beverly Hills, waiting for calls from their agents, I was on a plane with The Who, having a blast with Roger [Daltrey] and Pete [Townsend]. I lived in Italy for a year and half and circumnavigated the globe in my sailboat…twice. It was the best life ever.”

And she’s still going strong. At 81, she continues to act, appearing in such blockbuster films as Ocean’s Eight with Sandra Bullock and Just Getting Started opposite Morgan Freeman and Tommy Lee Jones, on such popular TV shows as Russian Doll, Better Things and The Bold Type and in various stage productions.

The secrets of her staying power?

“I’ve never entered a gym in my life, nor would I!” she boasts. “I’m not a great fan of what they call ‘positive thinking.’ I think it makes you stupid. But curiosity, creative imagination and independence are the things that have saved my life.”

The Higher the Hurdle

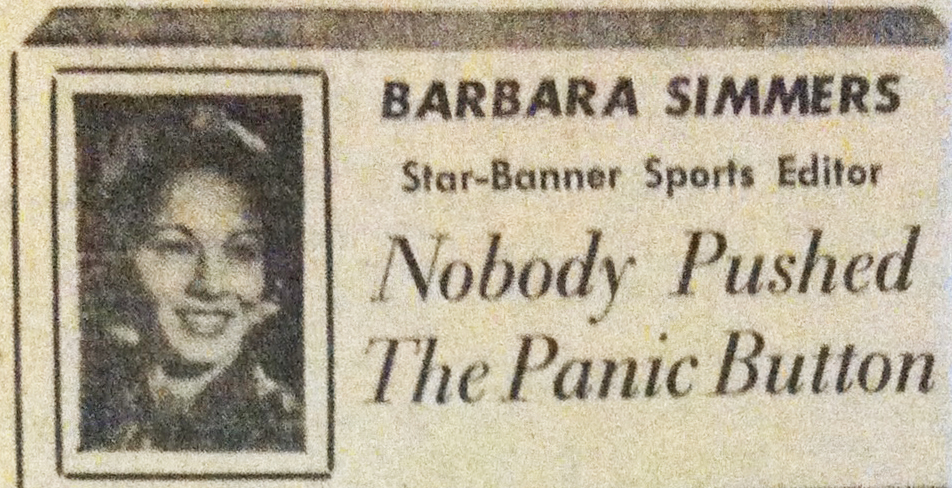

Barbara Simmers Caywood was the first female sportswriter in Florida, the first in Kansas and the third in the nation.

Her family moved to Ocala just before her freshman year at Ocala High School, from which she graduated in 1955.

“I knew I wanted to be a sportswriter when I was 15,” she offers. “During the summers before my junior and senior years at Southern Methodist University, I interned at the Ocala Star-Banner, doing a little bit of everything but mostly sports.”

In May 1959, just before she was to graduate, she got a call from Star-Banner Managing Editor Bernard Watts, who said the sports editor had quit and they would hold the job for her until she graduated, if she wanted it.

In May 1959, just before she was to graduate, she got a call from Star-Banner Managing Editor Bernard Watts, who said the sports editor had quit and they would hold the job for her until she graduated, if she wanted it.

“Of course, I said yes,” she states. “I couldn’t believe my luck. I didn’t have to apply for a job in a field where there were few, if any, women.”

She later became assistant sports editor at The Hutchinson News in Kansas, then sports editor, for 24 years. She recalls one issue involving her gender early in her career.

“In 1960, I was denied entry to the University of Kansas press box to cover a football game because I was female,” she says. “The News and I fought this prejudice and won. I was admitted the following year. Our fight became a national story.”

Tired of Kansas winters and missing her parents, Irene and Floyd Simmers, who were still living in Ocala, she returned to Florida in 1984 and accepted a position as a sportswriter for Florida Today in Melbourne, from which she retired in 2005. That same year, she was inducted into the Florida High School Athletic Association Hall of Fame and, in 2013, to the Space Coast Hall of Fame.

She says the best advice she ever got was from her father.

“He knew I would face challenges and told me, ‘Don’t ever back down from the first hurdle. If you do, the next one will be higher,’” she recalls.

Country Living

In 2016, Anthony farmer Marilyn Grant was given the Distinguished Service to Agriculture Award by the Florida Farm Bureau, in recognition of her outstanding contributions to the organization and her leadership in agriculture in the state. She also has been inducted into the Marion County Agricultural Hall of Fame.

“I was a farmer’s wife, but I was actually a farmer with him,” she sometimes had to remind people when she first joined the Marion County Farm Bureau Board of Directors in 1976. Many of her fellow board members, however, already knew her long history as a cattle farmer and peanut producer. Grant was elected the first female president of the board in 1996.

“I was a farmer’s wife, but I was actually a farmer with him,” she sometimes had to remind people when she first joined the Marion County Farm Bureau Board of Directors in 1976. Many of her fellow board members, however, already knew her long history as a cattle farmer and peanut producer. Grant was elected the first female president of the board in 1996.

After growing up on a farm and joining 4-H as a student member, Grant went on to be a 4-H leader for more than a decade. She helped organize the North Marion FFA Alumni Chapter and is still active with the group.

Although she loves working with young people already interested in agriculture, Grant also feels it’s important to teach all kids about the vital role farmers play in our society.

“That’s where their food comes from; they should understand it’s a part of their life,” she says. “They need to find out what’s involved. It’s not just going out there and throwing a seed in the ground. You’ve got to take [care of] it from the time it comes up till the time you harvest it—sometimes it’s months. You don’t get a check every week.”